Photos by Urban Libraries Council

A student at the Hartford, Conn., Public LIbrary constructs a robotic hand, learning about the bones of the hand in the process. The project comes from a STEM kit full of materials and lessons that librarians can take to Hartford Public Library branches.

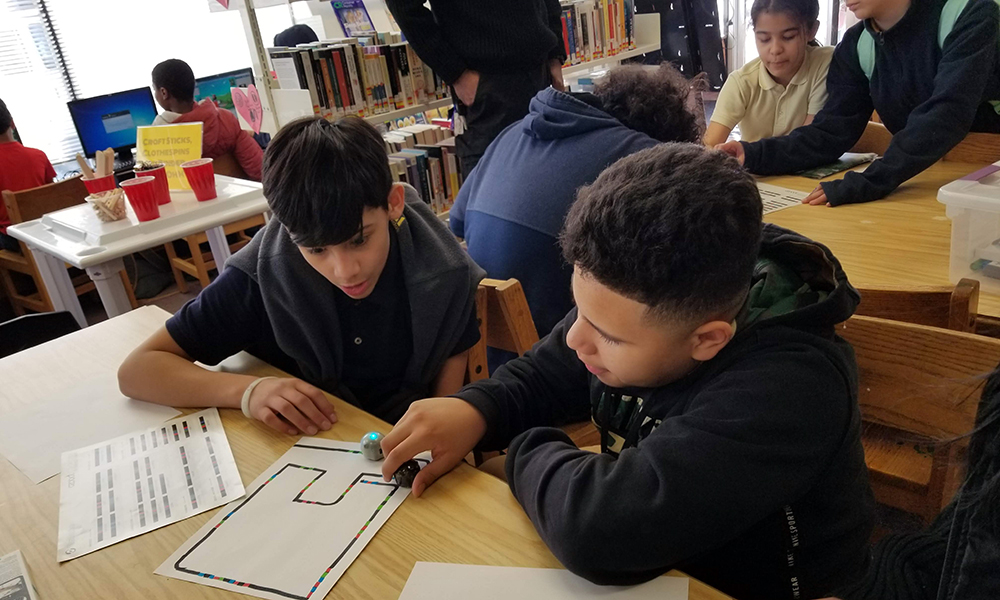

When a “mobile science lab” shows up after school at a branch library in Hartford, Conn., kids cluster around it. They look through microscopes, play with tiny programmable Ozobots or do a chemistry experiment.

Recently young teens at the Albany branch in Hartford took their own fingerprints, compared them with friends’ and created a database of fingerprints. At the Barbour branch in late March, kids built a robotic hand and moved the fingers by pulling attached strings.

It’s part of a project by the Urban Libraries Council to bring science and technology education to middle schoolers in underserved communities, with 11 library systems around the country involved.

Kids in San Jose, Calif., can learn to code as part of the mayor’s Coding 5K Challenge, administered by the San Jose Public Library. In Algona, Iowa, kids check out “toys” that teach science and math concepts.

In Gwinnett County, Ga., Spanish-speaking kids can do STEM activities in their native language at the county library.

“Each [library] is exploring an original program to find innovative ways to engage youth,” said Curtis Rogers, director of communications for the Urban Libraries Council, an association of the nation’s libraries.

Funding comes from the Institute for Museum and Library Services. The National Center for Interactive Learning at the Space Sciences Institute provides assistance to libraries as part of the two-year project.

Middle school a critical moment

The goal is to reach middle-school students who might not be getting exposure to STEM subjects. Middle schoolers are beginning to develop the mental capacities to take on higher-order STEM learning, Rogers said.

“They’re beginning to think seriously about their careers” but they’re also at a point where school disengagement happens, he said.

“Academic interests are really at risk of dropping off,” Rogers said.

In Hartford, a high percentage of children and families live in poverty, said Bridget Quinn-Carey, chief executive officer at the Hartford Public Library.

“We target students who may not have as much exposure to these resources as some in suburban school districts,” she said.

Librarians who bring the mobile STEM lab to each Hartford branch have been trained through the Connecticut Science Center and Manchester Public Schools, Quinn-Carey said. The STEM activities they offer are geared to 21st-century science standards.

When the librarians show up at a branch library, “the goal is to engage as many kids as are there and want to participate,” Quinn-Carey said.

Kids become aware of the STEM activities, and make a point of being there on days when projects are scheduled, said Marie Jarry, director of public services for the Hartford library.

“We recognize the need for STEM programs for the kids in Hartford,” she said. Although the Connecticut Science Center is a city resource, transportation and the cost of getting there are barriers for kids, she said.

A focus on discovery

Ten Hartford youth services librarians are trained to lead activities using the materials. Subject areas include biological science, earth science, engineering and applied science such as coding and robotics. The librarians don’t have to be science experts, Jarry said. They function as “a guide on the side” and focus on discovery.

“It doesn’t feel like science class,” she said, but it helps kids recognize areas of science they may not know about.

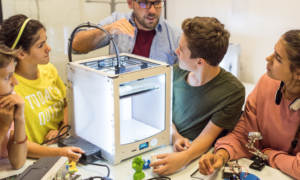

In addition to the mobile STEM materials, each Hartford branch library has a 3D printer. When a librarian recently found a printer wasn’t working, three teen girls helped her investigate the problem. They read through the manual and looked at how the filament was feeding into the printer.

Discoveries can occur that way, Jarry said.

‘The girls had the satisfaction of seeing themselves troubleshoot,” she said.

In another case, three younger girls discovered the 3-D printer could create some missing pieces for a Sorry! board game.

Two boys at the Park branch of Hartford Public Library work with Ozobots, putting code sequences together to make the tiny robots perform certain functions. The STEM lessons and materials are part of an Urban Libraries Council initiative to bring STEM activities to underserved middle-school students.

Taking science home

In Iowa, the Algona Public Library will be offering STEM kits that kids can check out like books. A kit may include Ozobots that kids take home.

“Kids would be programming them and telling them what to do” using color code markers, said Sonya Harsha, young adult librarian at the library

Students can check out micro:bits, handheld, programmable microcomputers that link to computers and teach kids coding. Other STEM kits could include Keva Planks for building — or even a knitting kit.

The point is to encourage young people to look at things in a new way, to become makers and possibly future creators, Harsha said.

Libraries an overlooked resource?

One institution — schools — is not enough to provide the education needed by a 21st-century workforce, Rogers said. Libraries are an important out-of-school learning resource, he said.

“Not every school has a 3D printer. But if the local library does, the kids can come in and [have access to it],” he said.

Schools and local governments can overlook the usefulness of libraries, he said.

Often, mayors have goals for a city such as workforce development, digital inclusion and greater STEM education that libraries can help with.

Which is why the Urban Libraries Council project focuses on partnerships with schools and local governments.

The Algona library, for example, is partnering with local businesses and organizations., including the Kossuth County 4-H, which will offer robotics activities, Harsha said.

The Council project also allows libraries to learn from each other.

“The really exciting thing is that we are getting to see what libraries across the country are doing with STEM,” Harsha said.

Also taking part in the project are the Chicago Public Library, Durham County Library in North Carolina, Mount Vernon City Library in Washington state; Pioneer Library System in Oklahoma; Prince George’s County Memorial Library System in Maryland, St. Louis County Library in Missouri and the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County in Ohio.