Atomazul/Shutterstock

.

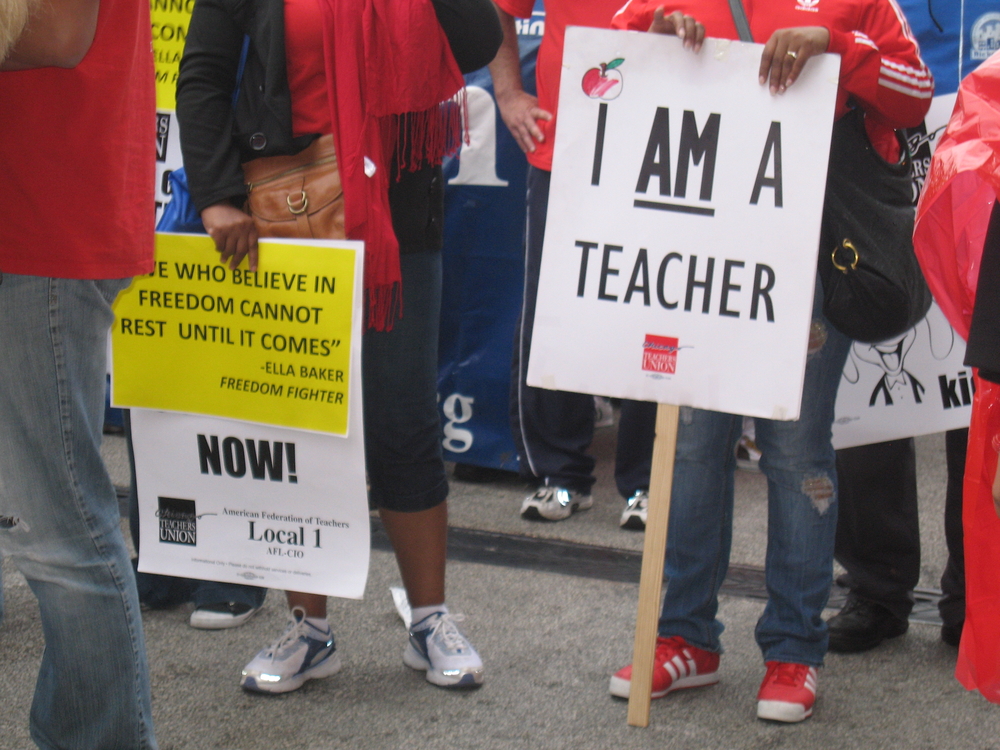

As more than 30,000 teachers in Los Angeles prepare to strike on Monday, some after-school programs find themselves in an awkward position.

On one hand they’re focused on providing a safe and enriching place for children in the afternoon — especially during the turbulence of a strike. On the other hand, the close relationship between schools and after-school programs in California means some after-school staff fear they could be called upon to cross picket lines and work in place of teachers.

The long-planned strike by United Teachers Los Angeles will remove the vast majority of teachers from classrooms in the Los Angeles Unified School District, which has nearly half a million students. Teachers are demanding higher pay, smaller class sizes and more nurses, librarians and counselors.

California’s per-pupil education spending is lower than many other states.

During a strike the school district plans to keep schools open.

In fact, it’s calling on other district employees to step into classrooms to replace teachers.

“Some [after-school programs] are run strictly by the district,” said Jen Dietrich, director of policy for the Partnership for Children & Youth, a California advocacy group for those working with underserved youth.

Leaders of programs with school district employees have expressed concern that their staff could be called in.

One program, LA’s Best, is an unusual public-private partnership. Founded 30 years ago by then-Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley and then-LAUSD Superintendent Leonard Britton, it functions as a nonprofit organization that is at the same time a division of the school district.

Other after-school programs are run on school sites by community-based organizations that contract with the school district. Their staff could also be asked to fill in for teachers, said some after-school leaders who did not want to be named.

In California, after-school programs are strongly connected with schools as a result of $600 million in state funding for expanded learning. California allocates more money for after-school programs than any other state in the nation, said Jen Rinehart, senior vice president of research and policy for the Afterschool Alliance.

Coupled with federal funds, this money is used to operate after-school programs in half the state’s public schools, according to a California Afterschool Network report. The focus is on high-poverty areas, with more than 75 percent of elementary schools in low-income areas served.

Based on school district documents, the Los Angeles Times estimates schools may be open with about 8 percent of the normal staff. This could include about 4,400 substitute teachers, other district employees and parent volunteers, according to the newspaper.

As a strike looms, families are worried and feel under pressure, Sandy Mendoza, director of advocacy for Families In Schools, told the Los Angeles Times.

The school district serves a mostly impoverished population: About 82 percent of students are below the poverty threshold. More than 70 percent are Latino and 50 percent or more have been learning English as a foreign language.

“We don’t want kids to be hurt in all of this,” said Tony Brown, chief executive officer of the Heart of Los Angeles after-school program, which serves 2,200 kids a year at its center. About 90 percent of students in the area live in poverty, he said.

“Schools in this neighborhood have tougher times [than schools in affluent areas],” he said. He doesn’t want to see anything occur that would put kids further behind.

The Heart of Los Angeles will be working as usual to provide classes and activities for about 500 kids per week. The nonprofit organization is funded through foundations and other private donations.

“We all want to see a strong education program,” Brown said.

“I’m disappointed that [the union and the school district] can’t figure out how to make adequate funding a common goal,” he said.