Educational Video Center

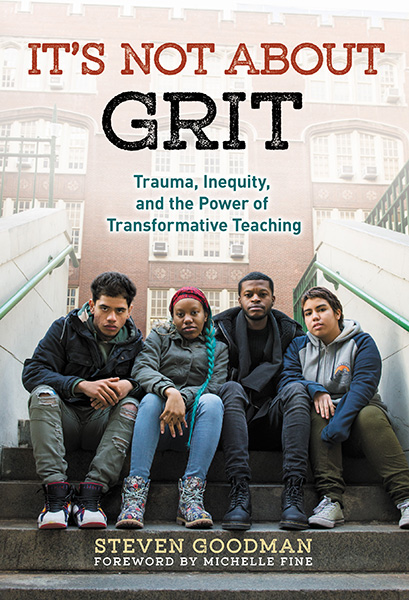

Students learn to create documentaries at the Educational Video Center.

Steve Goodman’s new book, “It’s Not About Grit: Trauma, Inequity and the Power of Transformative Teaching,” challenges the focus on grit as a critical trait for kids to succeed. It describes obstacles faced by young people, from poor housing to police harassment to involvement in the foster care system, and discusses how to work with youth in the face of such problems.

Goodman is founder of Educational Video Center in New York City, a nonprofit youth media organization that teaches documentary video to develop young people’s critical literacy, artistic and career skills.

Youth Today reporter Stell Simonton interviewed him.

Stell Simonton: What led you to write your book?

Steve Goodman: It comes out of my experience as the founding director of the Educational Video Center, working over 35 years with youth in New York City who have been in alternative and transfer schools and [have been] making documentaries in our after-school program. These are kids who have really been marginalized and silenced in many, many ways, and they were making these films about their lives, families, communities.

Making their experiences invisible

Steve Goodman

I saw how their struggles in school really were connected with their struggles out of school — whether it was … to survive in foster care or unhealthy housing situations or having family members incarcerated or deported. These were powerful stories that really helped me see the world through their eyes and see the systemic kind of obstacles they were struggling to overcome as well as their strengths and resilience …

At the same time, there’s been an increasingly popular narrative in education and youth development that is saying kids need more grit to really persevere to succeed in school. I felt it kind of rendered their experiences invisible or discounted them. I felt it was important particularly in this political time when so many communities are under siege to challenge that grit narrative …

SS: In the book, you mentioned some of the people who’ve written about character education and how important they believe it to be: Paul Tough, Carol Dweck and also Angela Duckworth, who popularized the whole notion of grit. What’s wrong with the focus on a character trait like grit?

SG: I think the focus is really becoming a dangerous distraction. Research over the past 50 years has given very well-documented evidence that links social conditions of poverty with diminished educational outcomes. Kids’ ability to concentrate and work hard and succeed in school is really undermined if they’re coming to school hungry or sick or traumatized [or worried about] being deported, evicted — all those kinds of things.

So if you believe that grit is the key ingredient to economic success and you conclude that the kids who fail to graduate each year, that they don’t have enough grit, it’s putting it on them. It’s individualizing what I think is really a social problem.

Wealth gap and inequality

To really understand the achievement gap you have to understand the wealth gap. The dropout rate for students in the lowest 25 percent of family income is about 5½ times greater than for kids in the highest 25 percent of income.

You also need to see it in the context of systemic racial inequality. We have 50 years after the Kerner Commission Report, and the black-white income gap is as wide as it was then. I think white household incomes are about 13 times that of black household incomes.

The grit narrative can be seen as a group blame for low-income kids and kids of color. And it lets you off the hook from giving funding to underfunded schools and communities if you say all you need is to change their mindset [rather than] any kind of policy or funding. It means you don’t really have to change those conditions.

One example is in the first chapter, which is about housing. You look at toxic mold and asthma and lead poisoning. They’re directly connected to children and families in poverty. Black children are, I think, 1½ times more likely than white children to suffer from lead poisoning A lead-poisoned child is about seven times more likely to drop out of school. It’s no fault of the child or lack of character. It has to do with housing and health policy. And what we allow to continue.

Can you imagine if white middle-class students suffered from lead poisoning or mold in their housing and we said, “Oh, just teach them to have more passion and perseverance” — instead of really addressing the underlying urgent problem. There’d be a massive outcry. Right now, we need to be outraged. We need to have more of a political will to do this.

Elevating youth voice

SS: As far as working with kids and teaching them, you have a different approach than some others do. The subtitle of your book uses the phrase “transformative teaching.” Can you tell me a little about what that means in the way you work with kids at the Educational Video Center?

SS: As far as working with kids and teaching them, you have a different approach than some others do. The subtitle of your book uses the phrase “transformative teaching.” Can you tell me a little about what that means in the way you work with kids at the Educational Video Center?

SG: I think it means combining a very youth-centered and community-based approach and really getting to know the students, who they are and the community they live in. I think it means bringing a social justice consciousness to the youth work, and it links individual youth growth and healing to family and community well-being. It’s always looking for possibilities and openings for social change and elevating youth voice and participation, particularly for those who are most silenced and marginalized …

SS: Is participatory action research the path through which you do that?

SG: It’s one of the strategies that I think is really important — where the young people and the communities that are the most impacted by the problem are the researchers. [They can] really investigate it and to see how it can be changed. I want to mention that I’ve been influenced and inspired by the transformative teaching approach of folks like Myles Horton and Septima Clark in the ’50s and ’60s in citizenship schools and later the freedom schools in the civil rights movement. They really saw that combination of learning and individual development to community change in action. They saw themselves and we can see ourselves as not only educators and mentors and youth workers but also as allies and advocates for the youth we serve.

Create compassionate community

SS: When teachers and youth workers want to go in that direction, what are some of the skills and practices that they need to develop?

SG: I think knowing how to create safe, welcoming spaces — I call it compassionate communities — where the youth know they’re being listened to, respected, supported. That’s a really important skill. It means being willing to make yourself vulnerable to the process and have hard conversations with the youth. I think another thing is knowing how to connect their lives to their learning, art and self-expression. It could be done through video documentaries … blogs or poetry or spoken word.

The third is knowing how to connect the youth to leaders and groups in the community and opportunities for school and community action. That’s where the participatory action research really comes in. It could be through community surveys, teach-ins on lead testing or gun violence, street harassment or maybe “know your rights” meetings for youth and families about their interactions with police or ICE [U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement]. It has to be rooted in the local situation of the school or after-school program and community. In many schools there already exist these after-school clubs which I write about and I think are important. People can learn to create things like them: restorative justice circles, the GSAs [genders and sexualities alliances], girls’ groups, Dreamers clubs. Those are really important spaces, too.

Other good organizations

SS: Someone reading your book who’s coming from another viewpoint might respond that the book is kind of black and white: Youth are good, big systems are bad. What would you say to that?

SG: I’ve worked in and with New York City schools for 3½ decades and I know many, many educators, school leaders and social workers, really caring people who are committed to working with and serving kids — working to try and improve these systems. There have been changes in them. But a lot of work remains to be done. I don’t think it’s that black and white but I think really listening to the youth we serve and hearing their stories and ensuring their voices are present I think it makes the school culture, the school and after-school programs that much richer, better and more humane places.

We need to look for those spaces where that can happen. That’s why I included video clips that are linked to the book. So it’s not just my voice or journalists or researchers, but [youth] voices. Kids need to be in dialogue. That dialogue is critical. It’s so important and so rare. It’s important to make happen whenever possible.

SS: Are there other organizations doing similar work that people might be interested in knowing about?

SG: I talk about the various groups that have done participatory action research project. Many around the country are doing important work. The Bread Loaf Teacher Network is one that is doing impressive work elevating youth voice. Youth Communications had done work in New York with foster care groups. In Appalachia, Appalshop has done wonderful work around youth documentaries. There are many groups around the country. Michelle Fine at the CUNY Graduate Center has written a lot around participatory action research. Highlander is well-known for that in Tennessee.

SS: Is there anything we have not touched on that you want to add about the book and about the way that you work with youth?

SG: The first audience for the book would be adults: educators, school leaders, social workers, youth workers. But it’s also important that the video clips be used as prompts for students and youth themselves because so often I think they feel they’re alone in the problems they’re experiencing. This is a way to show them faces and voices and stories that might resonate with them. They can see they’re not alone and they can feel more secure in sharing their stories. They can see that change is possible and learn about the systems and policies that created some of the problems. They can say: “I might feel hopeless now, but change is possible. I can feel more empowered.”

Editor’s note: Steve Goodman is happy to be contacted by readers who have questions or want more information. Email him at: sgoodman@evc.org