“Someone is going to come to your house in the middle of the night and take your parents, and you will be left all alone,” one middle-schooler taunted another.

When the two kids arrived at their after-school program, After-School All-Stars in Dallas, last year, the child who’d been taunted was angry and afraid.

Fear of deportation and threats about it are part of the new reality, said Marissa Castro Mikoy, executive director of the program, which serves 600 kids, many of them Latino or African-American, in six Dallas middle schools.

“It’s a new environment that we’re having to figure out,” she said.

In Muskegon, Michigan, the day after the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, a noose was found on the playground outside Glenside Early Childhood Center.

“This symbol does not belong in a place of learning and will not be tolerated by our district or the surrounding community,” Justin Jennings, Muskegon Public Schools superintendent, told the media.

To many people, these incidents reflect an increasingly intolerant climate that poses a threat to minority groups.

In October, the Southern Poverty Law Center counted 90 “hate incidents” in schools across the country, ranging from anti-Semitic graffiti to threats against LGBT students.

Some after-school providers are wondering how to navigate in this climate.

What youth workers can do

Last summer the teachers in Mikoy’s program in Dallas got training in RULER, a process to help kids recognize and regulate their emotions, developed by the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence. (RULER is an acronym that stands for recognizing, understanding, labeling, expressing and regulating emotions.) The staff also armed themselves with “know your rights” information for immigrant families, provided by the national office of After-School All-Stars.

Mikoy said the goal is to help kids process fear and anger, turn those feelings into a sense that they have some power and then become advocates for themselves. Kids can get information and educate themselves and their parents, she said.

RULER, for example, uses a “mood meter” to help a person identify emotions. Then the group leader helps a child move from intense and upset to a calmer emotion.

“All the teachers were trained to stop what they’re doing” when a child is upset, Mikoy said.

The process “gives kids another skill to use the rest of their lives,” she said.

In response to the current political climate, many youth-serving programs are taking “a social-emotional, positive communication approach,” said Ellen O’Connell, managing director of programs at PASE, the Partnership for After School Education, a nonprofit organization supporting quality after-school programs in New York City, particularly for underserved youth.

“We are trying to be proactive,” O’Connell said.

After-school programs are supporting their staff in bullying prevention, creating safe communities and having tough conversations in tough times, O’Connell said.

“A lot of organizations try to create a space in which people can have conversations,” she said.

The idea is to start within your own organization and community, she said. Work with your staff, create activities and routines and spaces in which to talk productively, she said.

Last fall, the organization hosted Beverly Daniel Tatum, former president of Spelman College and author of “Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations About Race.”

“Leadership matters,” Tatum told the after-school professionals at the PASE workshop. “Each of us has the capacity to change the narrative.”

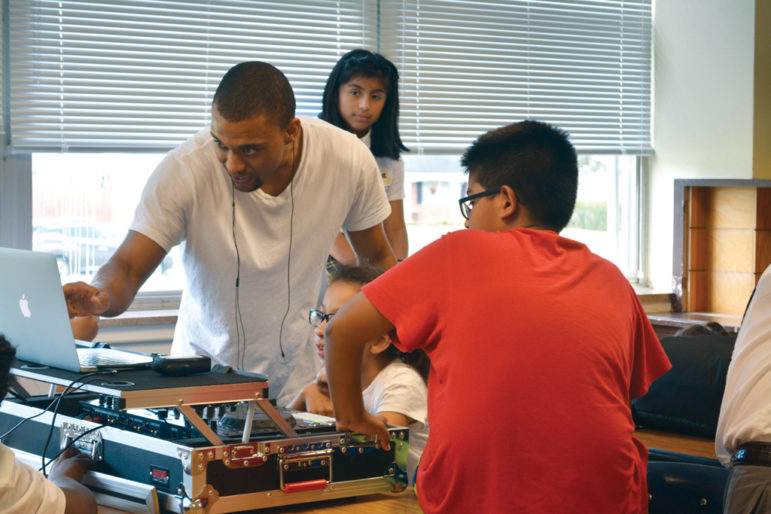

Feelings have run high this year at the After-School All-Stars program in North Texas, as Latino students have been taunted at school and some students fear deportation. Staff members use a process developed by the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence to help kids process their experiences.

Kids carrying burdens

Gina Warner, president of National AfterSchool Association (NAA), said she is seeing a lot of fear — particularly among young people who risk deportation. After-school staff are also seeing daily the effects of poverty and the accumulated stresses that go along with it, she said.

“Children are carrying that burden,” Warner said.

At the same time, the country has also faced several national disasters and mass shootings, she said. And sexual assault and harassment has come out into the open as women speak out about the actions of prominent men.

Warner said turbulent times are exactly when youth-serving professionals can function as a stabilizing force. She learned it during Hurricane Katrina.

Warner ran the Partnership for Youth Development in New Orleans, where she had lived for 15 years, when Hurricane Katrina hit. She had a 3-month-old daughter, and her house flooded with 8 feet of water.

“Numerous after-school organizations lost their facilities. After-school staff lost their homes,” she said.

At that time, she saw them mobilize and organize.

“Often, the first people back were the people working in after-school programs,” Warner said.

Out of that experience, Warner developed an expanded view of the role of after-school workers. The field can take a holistic approach, she said, teaching young people the practical skills of civic engagement and organizing.

“Our opportunity is to focus on a younger generation,” she said.

Youth can explore the political system. They can learn how to organize, speak in public, canvass neighborhoods, build coalitions and get out messages effectively, Warner said.

“It’s encouraging to me to see young people taking a leadership role,” she said. They believe they can affect positive change.

“Equally important is to be self-aware,” she said. The foundation of emotional intelligence is self-awareness, she said.

“This is something they can learn in after-school programs,” she said.

Tools for after-school

The NAA is providing tools for after-school professionals to help them during turbulent times, Warner said. One resource provides specific and practical advice about things after-school providers can do, ranging from how to organize the space in rooms to ways to talk to kids and co-workers, she said. The ideas match each of the core competencies spelled out in the NAA Core Knowledge and Competencies with effective practices.

In addition, the NAA will launch an online training promoting the well-being of staff. Often, after-school staff are focused on caring for others, but it’s very important to also care for themselves, she said.

It’s very important to create “a culture of well-being,” Warner said.

After-School All-Stars uses a social and emotional communications approach to empower kids and help them become advocates for themselves. The after-school organization seeks to arm kids with information, including facts about the rights of undocumented immigrants.

What about taking a stand?

To Maureen Costello, taking a stand is important. She is the director of Teaching Tolerance, a nonprofit that provides curriculum and professional development resources for educators and youth-serving organizations.

“We are experiencing a fraught moment in which it is impossible to stay neutral,” she wrote in a fall 2017 blog on the Teaching Tolerance website. “The students we teach in 20 years will want to know, ‘Where did you stand? What did you do to combat hate? How did you seek justice?’”

Hate speech is not up for debate, she wrote, and should not be legitimized in any way. In the foreword to Teaching Tolerance magazine just after the 2016 election, Costello advised appealing to shared democratic values when discussing political differences.

Holding productive discussions across political divides can happen, she wrote.

Not everyone agrees on the need for action, however. Walter Thompson, executive director of After-School All-Stars Atlanta, agrees that youth organizations should always be proactive, but the current political climate doesn’t play a big role in his after-school work.

“It has not affected After-School All-Stars Atlanta,” he said. “We are apolitical. We stay out of all of the discussion. We don’t want to polarize anybody.”

Hate speech is not a new phenomenon, he said.

“It exists, but we use those as teachable moments,” Thompson said. “If we see something, we’ll immediately develop a program to address that.”

For example, 10 years ago, After-School All-Stars Atlanta created Girl Talk, a program that addresses sexual exploitation and trafficking. Middle-school girls take part in small discussion groups led by female graduate students. They learn about sexual exploitation and how to recognize and respond.

The organization has had an anti-bullying program for 20 years, Thompson said.

His organization makes a point to be proactive in the face of sexual exploitation, bullying and gang pressures, he said. The organization serves 2,600 youth per year at 23 sites at middle schools, city recreation centers and two homeless shelters.

However, many others who work with youth see a troubling political landscape impacting today’s youth work.

For Mikoy, one good thing has come out of it. Her after-school program is not alone in its effort to support young people who feel under siege, she said: “Our community has really come together to help support our families.”