This story first appeared in The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education.

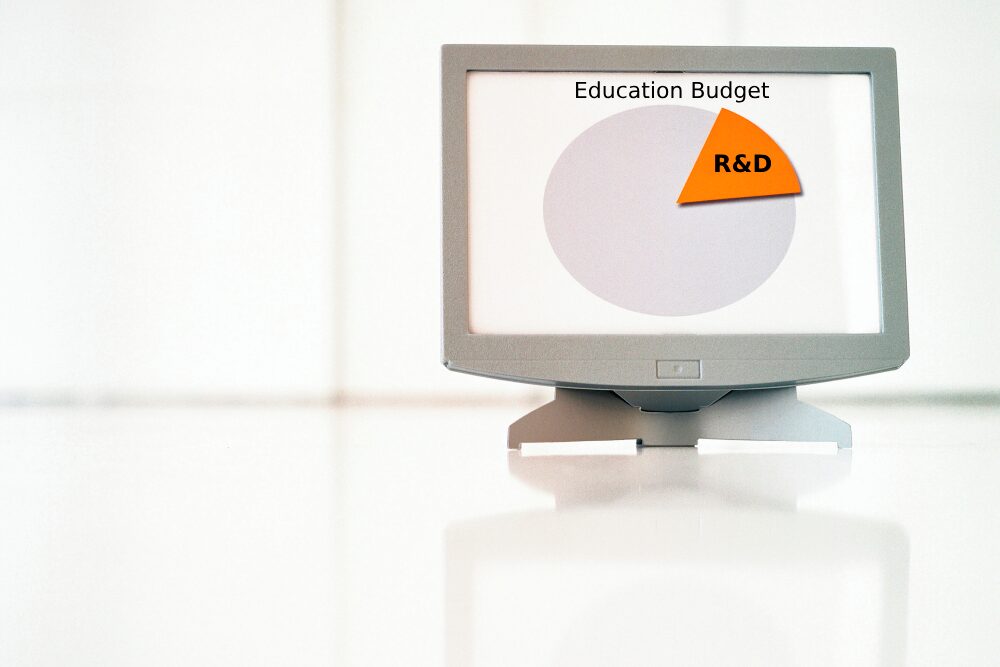

When COVID struck, scientists rushed to stem the pandemic in a coordinated effort that led to the creation of new vaccines in record time, saving millions of lives. These vaccines resulted from decades of investment by the federal government in mRNA research. Investing in research and development is a time-tested and effective way to solve big, complex problems. After all, R&D drives innovation in fields like health care, tech, energy and agriculture.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said about education.

The U.S. has never adequately invested in R&D related to education.

Persistent problems remain unsolved and the system is largely unable to handle unexpected emergencies, like COVID. Although strong research does exist, few education leaders use it to guide their decisions on behalf of kids.

Schwinn & Wright: In our states, we used the latest research to help students learn.

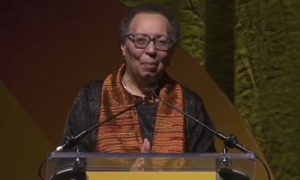

Courtesy Maryland State Dept. Education

Dr. Cary Wright, state superintendent of schools at the Maryland State Dept. of Education. Previously, she was State Superintendent of Education in Mississippi.

As former state education commissioners in Mississippi and Tennessee, we know that education research, when consulted and applied in classrooms, can yield huge academic gains for students.

Take literacy, for example.

For generations, Mississippi students ranked at or near the bottom in national reading scores, and Tennessee didn’t fare much better. In the late 1990s, the federal government poured millions of dollars into researching the most effective ways to teach young people how to read. But like a lot of good education research, those findings did little to change what was happening in classrooms and teachers colleges.

As education leaders, we knew we had to act on the findings, which supported systematic and explicit phonics-based instruction. It’s malpractice to look at stagnant achievement year after year and say, “Let’s keep doing the same thing.”

The key to each state’s progress was a desire to learn from researchers and implement evidence-based solutions — even if that meant admitting that current strategies weren’t working.

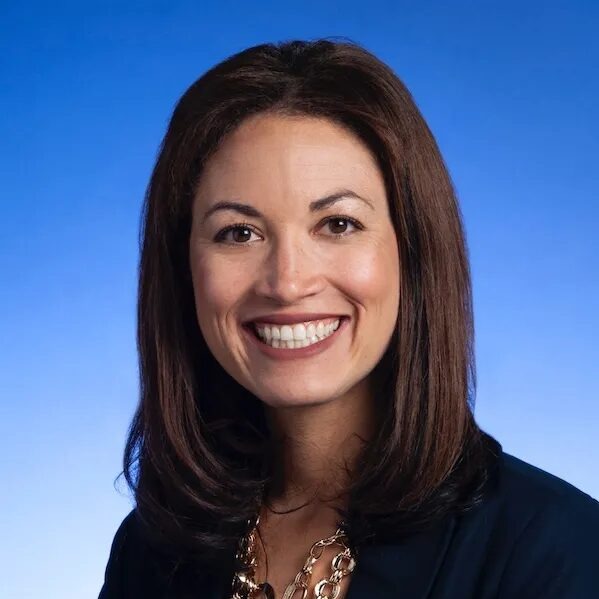

Courtesy University of Tennessee

Dr. Penny Schwinn, vice president for PK-12 and Pre-Bachelors programs at the University of Florida. Previously she served as a State Commissioner of Education in Tennessee.

So we aligned our states’ approaches to what the research said was most effective. In Mississippi, that meant training teachers on the science of reading. In eight years, Mississippi’s national literacy ranking for fourth graders improved 29 places, from 49th to 21st.

For Tennessee, it meant a revised program based on the science of reading and high-quality instructional materials, as well as new tutoring and summer school programs. This led to a nearly 8 percentage point jump in the third-grade reading proficiency rate – to 40% – in just two years.

There is still a long road ahead to get children in Mississippi and Tennessee where they need to be, but the key to each state’s progress was a desire to learn from researchers and implement evidence-based solutions — even if that meant admitting that current strategies weren’t working.

Congress and state leaders must make education innovation a priority.

That’s not an easy admission, but from our experience leading education efforts in states both red and blue, we believe that education R&D should be the foundation for every decision that affects student learning. That’s why we are calling on leaders in states and in Congress to make it a top priority.

Why now?

First: Students lost significant learning due to COVID, creating an academic gap that may take years to close. Solving this problem requires innovative programs, new platforms and evidence-based approaches. The status quo isn’t sufficient. Education leaders and policymakers need to move with urgency.

Second: America is on the cusp of a new age of technological opportunity. With AI-powered tools like ChatGPT and advances in learning analytics, researchers and developers are just beginning to tap the vast potential these technologies hold for implementing personalized learning, reducing teachers’ administrative responsibilities and improving feedback on student writing.

[Related report: Leveraging AI to transform education]

They can even help teachers make sense of education research. Without adequate R&D, however, these technologies may fall short of their potential to help students or – worse – could interfere with learning by perpetuating bias or giving students incorrect information.

But in order to tap this vast potential, the R&D process must be structured around the pressing needs facing schools.

Educators, researchers and developers must collaborate to solve real-world classroom problems.

Too often, tech tools are conceived by companies with sales in mind, while research agendas are set by academics whose goals and interests do not always align with what schools truly need. Both situations leave educators disconnected from the R&D process, so it’s no wonder they are often unenthusiastic when asked to implement yet another new strategy or tool.

The field needs educators, researchers and companies working together to prioritize which problems to solve, what gets studied, what interventions get developed and where the field goes next. Instead of education leaders selecting from an existing menu of tools and approaches, they should be driving the demand for better options that reflect their students’ needs.

Leaders at both the state and federal levels have an important role to play in making this standard operating procedure.

At the state level: Superintendents and other leaders must be deliberate in using research to make evidence-based decisions for the benefit of students. Every state and school district has access to a federally funded Regional Education Laboratory, which stands ready to generate and apply evidence to improve student outcomes. But too few leaders take advantage of this resource. Local universities offer opportunities for partnerships that can benefit K-12 students.

[Related: ‘Not waiting for people to save us’: 9 school districts combine forces to help students]

For example, the Tennessee Department of Education and the University of Tennessee established a reading research center to study the state’s literacy efforts. Programs like Harvard University’s Strategic Data Project Fellowship and the Invest in What Works State Education Fellowship can provide states and districts with talented and affordable experts who can help build their in-house research capabilities. If you’re a state or district education leader who hasn’t yet tapped into your Regional Lab, forged partnerships with universities or hired an R&D fellow, these are three easy ways to start becoming an evidence-driven leader.

At the federal level: Congress can do much more to engender a bolder approach to education R&D. A great first step would be to create a National Center for Advanced Development in Education, at the Institute of Education Sciences, the research arm of the U.S. Department of Education.

This center would tackle ambitious projects not otherwise addressed by basic research or the market — and support interdisciplinary teams to conduct outside-the-box R&D. The idea is to create a nimble, flexible research center modeled after agencies like DARPA, whose research produced game-changing inventions like GPS and the Internet. Rather than just making incremental changes, the center would strive to solve the biggest, most complex challenges in education and develop innovations that could fundamentally transform teaching and learning.

DARPA for Education’ is a good start. Now, Congress must do more]

Congress can make this possible by passing the bipartisan New Essential Education Discoveries (NEED) Act (H.R. 6691), soon to be introduced in the Senate. Or, the center could be included in a reauthorization of the Education Sciences Reform Act, legislation that shapes the activities of the Institute of Education Sciences and is long overdue for an update.

This is the leadership students need from Congress and state officials, now.

Education innovation won’t happen if school systems continue to rely on old ways of thinking and operating.

Education needs a bold, “what if” mentality – embracing ambitious goals, smart risks, and game-changing solutions – all guided by the north star of evidence. Only when educators, researchers, companies and policymakers champion a new model for education R&D, will schools pioneer a future where every student receives a truly transformative education.

***

Dr. Penny Schwinn is the Vice President for PK-12 and Pre-Bachelors Programs at the University of Florida. Previously she served as a State Commissioner of Education in Tennessee. With over two decades of bipartisan experience, Dr. Schwinn is a national education leader and as held a variety of leadership roles in public education.

Dr. Carey M. Wright is the State Superintendent of Schools at the Maryland State Department of Education. Previously, she was State Superintendent of Education in Mississippi. As one of the longest-serving state chiefs of the 21st century, she retired in Mississippi in June 2022. Her tenure there was longer and marked by more student gains than any State Superintendent of Education since the Education Reform Act of 1982 established the Mississippi State Board of Education.

fter steering Mississippi’s unlikely learning miracle, Carey Wright steps down]

This story was produced by The 74, a non-profit, independent news organization focused on education in America. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.