This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education.

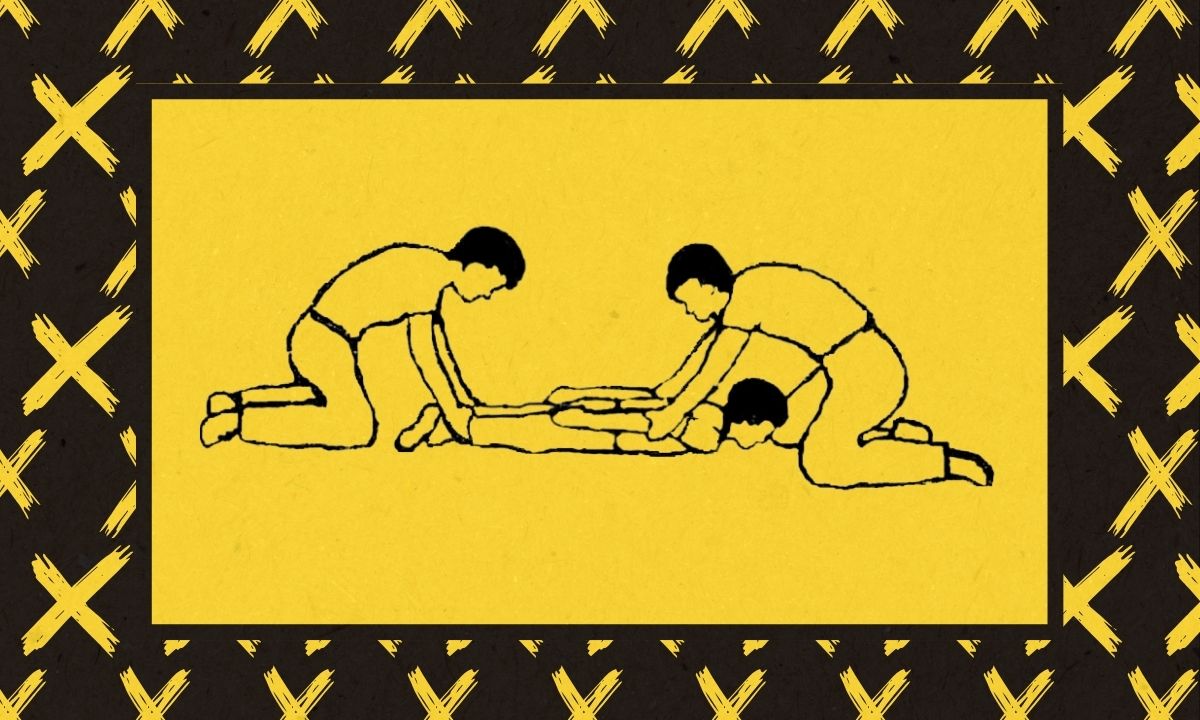

When they voted earlier this year to let police officers use a dangerous form of restraint on students in schools, Minnesota Democratic lawmakers said they did so because they had brokered a compromise. A task force made up of law enforcement agencies, disability advocates and others would create a model policy aimed at minimizing the use of prone restraint — the face-down hold Minneapolis police officers used to immobilize George Floyd as he suffocated.

Now, however, some advocates say they fear that the task force’s law enforcement majority wants to shut down discussion of the issues at the core of the raging debate over the perils of stationing cops in schools.

Representatives of kids with disabilities, children of color say task force is shutting down discussion of guidelines for cops in schools.

At the task force’s first meeting, in June, the executive director of the Minnesota Board of Peace Officer Standards and Training announced that the group would not discuss prone restraints or use of force, says Khulia Pringle, the task force member who represents Solutions Not Suspensions. Her coalition consists of community groups including disability and racial equity advocates.

“He said, ‘This is not a philosophical debate and we are not going to go beyond the substance of the statute,’ ” Pringle quoted Erik Misselt as saying. “I thought for sure we would get into the weeds of what we were there for.”

The board, which licenses law enforcement officers, is responsible for overseeing development of the model policy.

The compromise legislation, Pringle and other advocates say, requires the committee to address a number of issues pertaining to the use of school resource officers, whose campus presence dramatically increases student arrests. They believed the model policy — to be adopted by law enforcement agencies whose officers work in schools — would specify when police can act in schools and lay out alternatives to the use of force.

The task force is scheduled to hold the second of four planned meetings July 18 and to agree on a finished model policy in mid-September. So far, members of the group have been given little research on policies guiding police presence in schools, causing some advocates to fear the end product won’t reflect best practices.

“The public was told this was sorted out, that children would be protected by a model policy,” says Erin Sandsmark, another Solutions Not Suspensions leader.

“To say you can’t do the job without holding a child face-down in a dangerous hold seems extreme to us.”

By law, the task force had to include representatives of the police licensing board and five other law enforcement organizations, four statewide education organizations and three community groups — one of them representing special education students. Maren Christenson, executive director of the Multicultural Autism Action Network — one of two disability-focused organizations in the Solutions Not Suspensions coalition — is concerned about the lack of representation for the students most impacted.

“We know who is on the receiving end of most types of disciplinary actions in schools,” she says, “especially students of color with disabilities. Limiting their representation in this discussion doesn’t help.”

The U.S. Department of Education has called for banning prone restraints, and the Justice Department in 2022 issued extensive recommendations for in-school policing.

More recently, the Government Accountability Office released research that draws on federal arrest data, which revealed dramatic disparities by race, gender and disability status. At schools where police are stationed, teachers and administrators often call on them to deal with student misbehavior, the report notes, dramatically ratcheting up arrest rates.

[Related: What happens when suspensions get suspended?]

In the wake of Floyd’s 2020 murder, numerous districts throughout the country — including Minneapolis — stopped stationing police in schools. In 2023, Minnesota lawmakers banned the use of in-school prone restraints altogether.

But with election year politics already in play, in-school policing remained a red-hot topic. Although they control the state House of Representatives, state Senate and governorship, Minnesota Democrats have straddled a rural-urban divide on policing since Floyd’s death. After in-school prone restraints were outlawed

… at least 16 suburban and rural law enforcement agencies pulled officers out of schools, arguing that they could not work if they were not allowed to use the holds.

Fearing the controversy would cost the party seats in November, this year Democrats stripped the ban from state law but added detailed requirements regarding training, data collection and the creation of a model policy. Among other things, the law says the policy must prohibit calling on cops to enforce school rules or assist educators with discipline; specify de-escalation techniques and other alternatives to the use of force; create a timeline for school resource officers to complete extensive, new training on juvenile issues also called for under the law; and protect student data.

Debate during the legislative session was hampered by a near-total lack of data on police presence in Minnesota schools. No one tracks how many school systems have contracts with law enforcement agencies, how many officers are stationed in schools and how often they intervene with students — much less which ones and why.

“Reporters kept asking, ‘Do you know how many kids are restrained?’ ” says Pringle, the only person of color on the task force. “And [lawmakers] kept saying, ‘That’s one of the things we will now know.’ ”

It’s not clear to her or other advocates present at the group’s first meeting if data will be collected or whether any agency will track law enforcement contracts with school systems.

Disability advocates nationwide for years have campaigned to outlaw prone restraints, which were linked to 79 child deaths between 1993 and 2018.

In 2015, Minnesota passed a law prohibiting school staff from using the hold and requiring education and school leaders to reduce other types of physical holds and seclusion, which are used disproportionately on children with disabilities.

Though COVID-related school closures skew the data, the use of physical restraints involving students with disabilities in schools fell from 19,000 in the 2017-18 school year to some 10,000 in 2021-22. Black and Native American children are disproportionately likely to experience restraint, as are autistic students and those with emotional behavioral disorders.

In preparation for the July 18 meeting, participants were asked to submit examples of model policies for discussion. Solutions Not Suspensions submitted the only guidance to go beyond the law’s basic scope, according to a meeting preparation packet emailed to participants. Created by the American Civil Liberties Union, it contains detailed information on many of the topics raised by the legislature.

The ACLU document distinguishes between disciplinary misconduct, which should be handled by school staff, and criminal behavior requiring police intervention.

School resource officers can’t be called in when a student is disruptive or involved in a fight that doesn’t involve a weapon or result in injury, for example. The rules also require police to collect data on their in-school activities and make it publicly available.

Other models submitted include a policy drafted by the Minnesota School Boards Association and manuals used by a school system in Georgia that operates its own police department. The Georgia materials do not address prone restraint, instead defining different levels of physical force, ranging from benign redirection to lethal steps.

[Related: School interventions offer best shot at reducing youth violence]

Like most school board organizations, the Minnesota association typically creates policies for its members, many of whom serve on boards of districts that are too small to generate their own. So that it can be used in many contexts, this type of model policy is typically very general. The Minnesota version simply reiterates the main points of the new state statute without addressing alternative strategies.

The task force will use the school board policy as a starting point, law enforcement board officials said in an email sent to members along with an agenda for their July meeting. The group is supposed to have a finished model policy by September, after which the law enforcement board will decide whether to adopt it.

In an emailed response to The 74’s request for comment about advocates’ concerns, Misselt wrote, “All members of the working group have the opportunity to discuss their opinions and viewpoints during the meetings and all participants are expected to do so.”

Lawmakers who voted both for and against allowing police to use prone restraints said they have not yet received updates on the development of the model policy and thus can’t comment. Disability advocates said they expect several legislators will be present at the task force’s next meeting.

In the end, Pringle is concerned that the task force won’t have time to come up with a nuanced recommendation. “I’m just confused as to how in the world this is supposed to work,” she says. “It feels like whatever happens in this model policy is going to be focused on the adults.”

***

Beth Hawkins is a senior writer and national correspondent at The 74. She has covered education since 2000, writing about K-12 schools for Minnesota’s nonprofit public policy news site, MinnPost, followed by a recent stint as Education Post’s writer-in-residence. Hawkins’ stories have appeared in More, Mother Jones, the Atlantic, U.S. News & World Report, Edutopia, EducationNext, the Hechinger Report and numerous other outlets.

The 74 is a nonprofit news organization covering America’s education system from early childhood through college and career. The 74’s journalists aim to challenge the status quo, expose corruption and inequality, spotlight solutions, confront the impact of systemic racism, and champion the heroes bringing positive change to our schools. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74.