This story was originally published by Chalkbeat. Sign up for their newsletters.

I was 21 when I started teaching at Hope-Hill Elementary School in Atlanta. I had big dreams and bold ideas — some held, others fettered as the toll of teaching in majority Black schools suffering from resource deprivation took hold.

My first year was complicated by the fact that C.W. Hill Elementary closed, or merged with John Hope Elementary, depending on whom you ask. And in an effort to make the devastating change more palatable, John Hope Elementary School became Hope-Hill Elementary School.

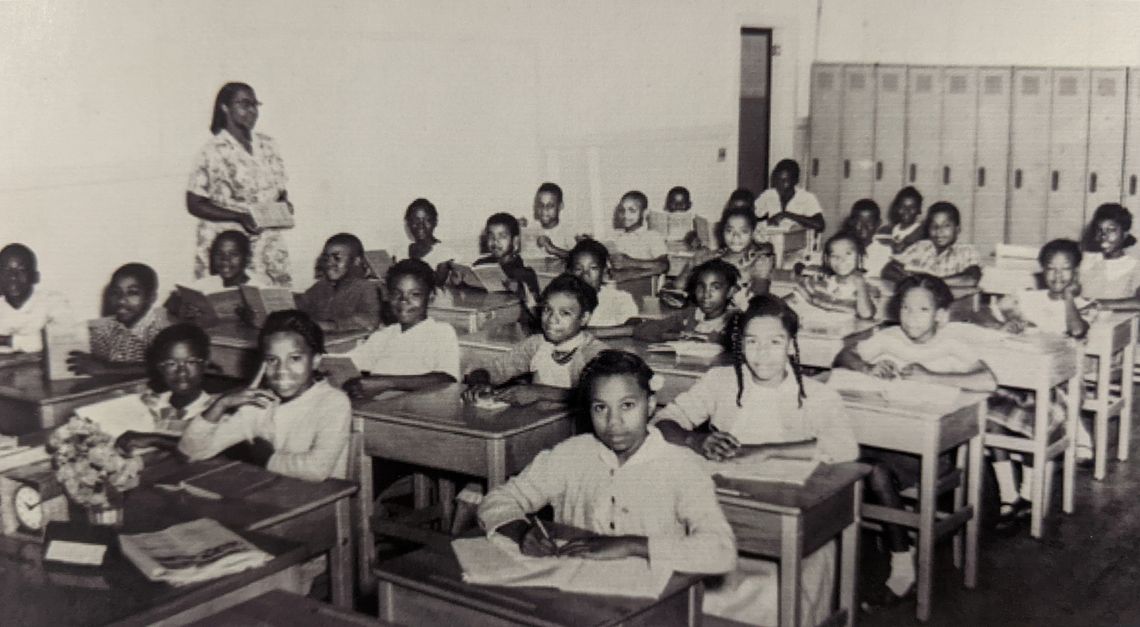

Courtesy of Shannon Paige Clark

Shannon Paige Clark

This was my introduction to austerity measures, or the practices in school districts that justified slashing resources, slimming budgets, and closing schools, which are often in working-class Black communities.

Hope-Hill was led by Black women and almost all of my colleagues were Black, as am I. We did the best with what we had, and many of us used our own resources to make our classrooms special. At the end of that year, I felt grateful to be in a community that felt like home, and I was happy I survived the first year of teaching in a system that set me and my colleagues up to fail.

Midway through my summer break, I received a surprise phone call inviting me to interview for a new teaching position. A neighboring school principal informed me that my name was listed as eligible for hire, which meant I was surplused, unbeknownst to me. In other words, I was the last one hired and the first one fired because the enrollment numbers at Hope-Hill did not justify the existing number of teachers — another austerity measure.

Two years, two schools. New grade, new curriculum. I was already disillusioned and not sure I had the wherewithal to start over so soon. In fact, research shows that Black teachers leave the teaching profession more than educators in other racial groups, commonly citing burnout, disrespect, and racism.

I stuck it out. I was a brand new teacher for the second year in a row.

‘Did you say segregation ended?’ My student’s question speaks to the reality inside classrooms.

One day, I read a book about Ruby Bridges to my third grade students. I began to explain that schools were no longer segregated, in part because of the courage of children like Ruby, who in 1960 became the first Black student to attend a Louisiana school that had previously been all white.

“Did you say segregation ended, Ms. Paige?”

Tatianna’s question stopped me mid-sentence.

I thought to myself: I did, but if you look around this classroom and school, you would not know.

“Yes,” I told Tatianna. ”There are no longer laws, or rules, that forbid Black people like you and I from going to schools with white children.”

Then Tyreik chimed in, “So where all the white people?”

I replied, “That’s a good question. It’s tricky. Many of the neighborhoods we live in are still segregated even though the law does not say they have to be that way. And since we live in segregated neighborhoods, many schools still look like they did when the law said schools must be segregated because most children go to school near their houses.”

If they were older, I would have told them about anti-Blackness and redlining and the ways unjust policies have been used to maintain de facto segregation.

Today, schools remain largely segregated by race and class, and I often think back to my first two years in the classroom, starting in 2009. All but three of my students were Black, and most of my colleagues were Black, too. We lacked material resources, but we had a lot of heart.

Black teachers leave the teaching profession more than educators in other racial groups, commonly citing burnout, disrespect, and racism.

My teaching and coaching experiences in schools that were highly segregated by race and class fuels my passion for researching hypersegregated schools, places that 70 years after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling are still separate and unequal.

According to the Center for American Progress, some 40% of America’s more than 1,700 school districts are hypersegregated, where at least three-quarters of students are from low-income households. Hypersegregated schools tend to get by on the bare minimum. Facilities may be inadequate, and the consequences of racial segregation and concentrated poverty make it harder to learn and even harder to thrive.

In my research, I focus on hypersegregated school communities where people lack the resources they need. I call this resource deprivation because those in power make decisions that deny necessary resources.

A CBS News investigation found that majority Black school districts have less money, and the students suffer as a result. School funding disparities exist across states, districts, and schools; high-poverty districts with the most students of color receive less funding per student, on average. EdBuild, which parsed school funding systems, determined that, nationwide, predominantly white school districts get $23 billion more than predominantly non-white districts, despite serving a similar number of children. This is resource deprivation.

[Related: Schools are more segregated than 30 years ago. But how much?]

Hypersegregation fuels inequity, and despite the landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education 70 years ago, the resource deprivation that existed in 1954 remains for far too many Black children who are relegated to underfunded schools.

There are miracle workers in many of these school communities. But the weight of fighting a separate and unequal system can diminish the hopes and dreams of even the most idealistic people — educators and students alike.

***

Shannon Paige Clark, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern. She researches educational policies and family engagement in school.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.