This story was originally produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news outlet focused on education.

LOS ANGELES — When Abram van der Fluit began teaching science more than two decades ago, he tried to ward off classroom disruption with the threat of suspension: “I had my consequences, and the third consequence was you get referred to the dean,” he recalled.

Suspending kids didn’t make them less defiant, he said, but getting them out of the school for a bit made his job easier. Now, suspensions for “willful defiance” are off the table at Maywood Academy High School, taking the bite out of van der Fluit’s threat.

Lawmakers argued that suspensions for relatively minor infractions, like talking back to a teacher, harmed kids, including by feeding the school-to-prison pipeline.

Mikey Valladares, a 12th grader there, said when he last got into an argument with a teacher, a campus aide brought him to the school’s restorative justice coordinator, who offered Valladares a bottle of water and then asked what had happened. “He doesn’t come in … like a persecuting way,” Valladares said. “He’d just console you about it.”

Being listened to and treated with empathy, Valladares said, “makes me feel better.” Better enough to put himself in his teacher’s shoes, consider what he could have done differently — and offer an apology.

This new way of responding to disrespectful behavior doesn’t always work, according to van der Fluit. But “overall,” he said, “it’s a good thing.”

In 2013, the Los Angeles Unified School District banned suspensions for willfully defiant behavior, as part of a multi-year effort to move away from punitive discipline. The California legislature took note. Lawmakers argued that suspensions for relatively minor infractions, like talking back to a teacher, harmed kids, including by feeding the school-to-prison pipeline. Others noted that this ground for suspension was a subjective catch-all disproportionately applied to Black and Hispanic students.

A state law prohibiting willful defiance suspensions for grades K-3 went into effect in 2015; five years later, the ban was extended through eighth grade. Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law adding high schoolers to the prohibition. It takes effect this July.

A Hechinger Report investigation reveals that the national picture is quite different. Across the 20 states that collect data on the reasons why students are suspended or expelled, school districts cited willful defiance, insubordination, disorderly conduct and similar categories as a justification for suspending or expelling students more than 2.8 million times from 2017-18 to 2021-22. That amounted to nearly a third of all punishments reported by those states.

As school districts search for ways to cope with the increase in student misbehavior that followed the pandemic, LAUSD’s experience offers insight into whether banning such suspensions is effective and under what conditions. In general, the district’s results have been positive: Data suggests that schools didn’t become less safe, more chaotic or less effective, as critics had warned.

The Los Angeles school district’s decade-old ban on suspensions for ‘willful defiance’ has benefited students — but also required a major investment in less punitive discipline methods

From 2011-12 to 2021-22, as suspensions for willful defiance fell from 4,500 to near zero, suspensions across all categories fell too, to 1,633, a more than 90 percent drop, according to state data. Those numbers, plus in-depth research on the ban, show that educators in LAUSD didn’t simply find different justifications for suspending kids once willful defiance was off limits. Racial disparities in discipline remain, but they have been reduced.

Meanwhile, according to state survey data, students were less likely to report feeling unsafe in school. During the 2021-22 school year for example, 5 percent of LAUSD freshmen said they felt unsafe in school, compared with more than three times that nine years earlier. As for academics, state and federal data suggest that the district’s performance didn’t fall after the disciplinary shift, although the state switched tests over that decade, making precise comparison difficult.

“It really points out that we can do this differently, and do it better,” said Dan Losen, senior director for the education team at the National Center for Youth Law.

[Related: Preventing suspensions — Tackle discipline problems with empathy first]

A pile of research demonstrates that losing class time negatively affects students. Suspensions are tied to lower grades, lower odds of graduating high school and a higher risk of being arrested or unemployed as an adult. Losen said this is in part because students who are suspended not only miss out on educational opportunities, but also lose access to the web of services many schools offer, including mental health treatment and meals.

That harm is less justifiable for minor transgressions, he added. And “what makes it even less justifiable is that there are alternative responses that work better and involve more adult interface for the student, not less.”

In part because of this research, Los Angeles, and then California, increasingly focused on disciplinary alternatives as they eliminated or narrowed the use of suspensions for willful defiance.

Gail Cornwall for The Hechinger Report

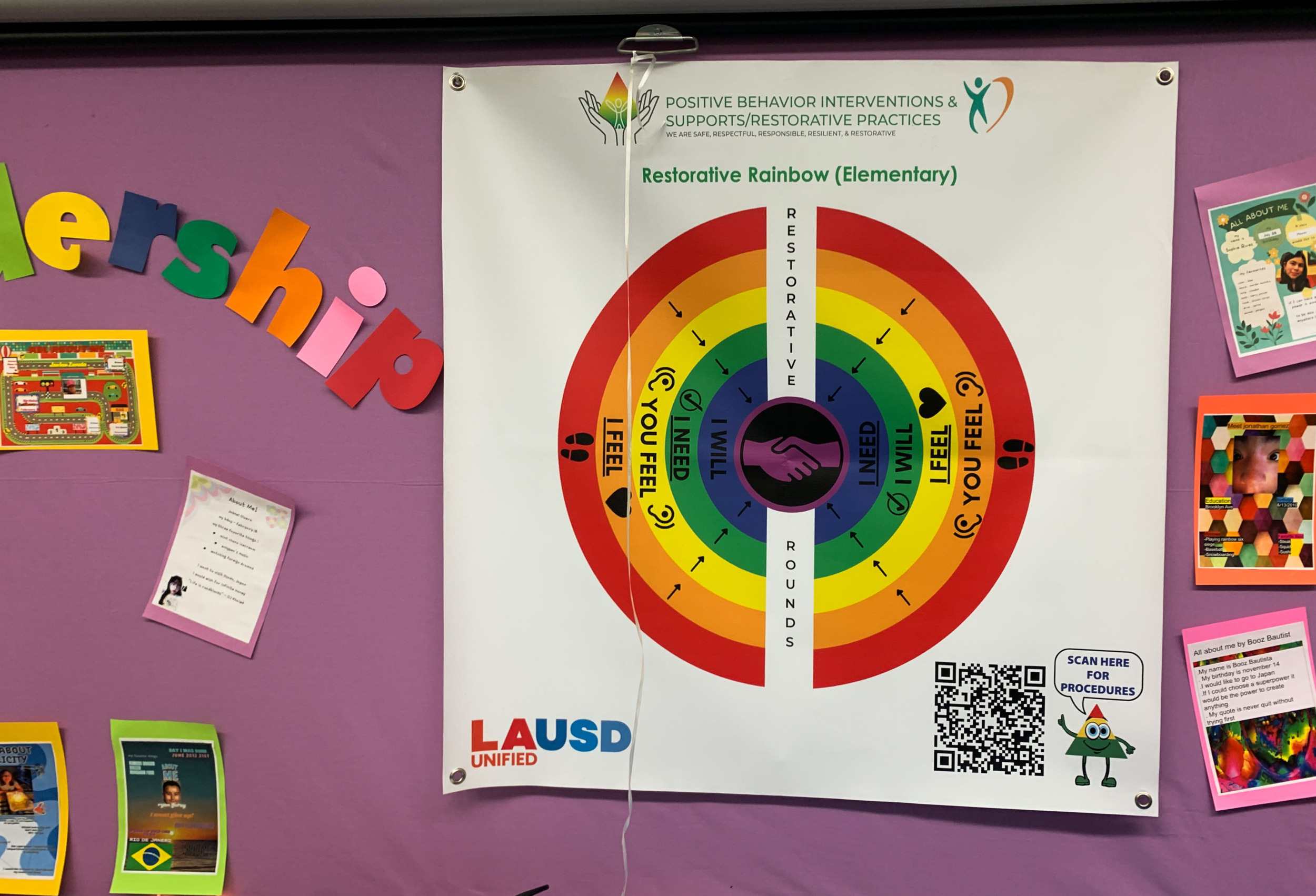

A “restorative rounds” poster on the wall of Brooklyn Avenue School in East L.A. creates a protocol with steps and “sentence-starters” that teachers and students can use to process conflict, reconnect and be heard.

LAUSD gradually scaled up its investment, rolling out training in 2015 for teachers and administrators in “restorative” practices like the ones Valladares described. Educators were also encouraged to implement an approach called positive behavioral interventions and supports. Together, these strategies seek to address the root causes of challenging behavior. That means both preventing it and, when some still inevitably occurs, responding in a way that strengthens the relationship between student and school rather than undermining it.

The district also created new positions, hiring school climate advocates to give campuses a warm, constructive tone, and “system of support advisors,” or SOSAs, to train current employees in the new way of doing discipline. From August to October 2023, SOSAs offered 380 such sessions; since July 2021 alone, more than 23,000 district staff members and 2,400 parents have participated in restorative practices training, according to LAUSD.

[Related: Breaking walls, building bridges: A call for restorative justice in school discipline]

All that work has been expensive: The district budgeted more than $31 million for school climate advocates, $16 million for restorative justice teachers and nearly $9 million for the SOSAs for this school year. Combined with spending on psychiatric social workers, mental health coordinators and campus aides, the district’s allocation for “school climate personnel” totaled more than $300 million this year.

That’s money other districts don’t have. And it’s part of what prompted the California School Boards Association to support the recent legislation only if it were amended to include more cash for alternative approaches to behavior management.

Gail Cornwall for The Hechinger Report

At William Tell Aggeler High School, Robert Hill, the school’s dean, calmly shadows an angry, upset student, prepared to help restore calm rather than impose a punishment. His response is part of LAUSD’s transition to a more positive, relational form of discipline meant to keep students from losing educational minutes.

Troy Flint, the organization’s chief communications officer, said administrators in many remote, rural districts in particular do not have the bandwidth, or the ability to hire consultants, to train staff on new methods. Their schools also often lack a space for disruptive students who have had to leave class but can’t be sent home, and lack the adults needed to supervise them, he said. “You often have situations in these districts where you have a superintendent or principal who’s also a teacher, and maybe they drive a bus – they don’t have the capacity to implement all these programs,” said Flint.

The state’s 2023 budget allocated just $7 million, parceled out in grants of up to $100,000, for districts to implement restorative justice practices. If each got the full amount, only approximately 70 districts would receive funding — when there are more than a thousand districts in the state. Even then, the grants would give each district only a small fraction of what LAUSD has needed to make the shift.

[Related: Hidden expulsions? Schools kick students out but call it a ‘transfer’]

“The district doesn’t have my back.” Researchers, legislators and school board members, wear “rose-colored glasses.”

Abram van der Fluit, science teacher,

Maywood Academy High School

Even in LAUSD, the money only goes so far. The district of more than 1,000 schools employs nearly 120 restorative justice teachers, meaning only about a tenth of schools have one. Roughly a third of schools have a school climate advocate. SOSAs are stretched thin too, in some cases supporting as many as 25 schools each, and some budgeted SOSA positions haven’t been filled. There’s also the continual threat of lost funding: In recent years, the district has been using federal pandemic funding, which ends soon, to pay for some of the work. “School sites are having to make hard choices,” said Tanya Ortiz Franklin, an LAUSD school board member.

And money hasn’t been the district’s only challenge. Success requires buy-in, and buy-in requires a change in educators’ mindsets. Back in 2013, van der Fluit recalls, his colleagues’ perspective on the ban on willful defiance suspensions was often: “What is this hippie-dippie baloney?” Teachers also questioned the motives of district leaders, wondering if they wanted to avoid suspending kids because school funding is tied to average daily attendance.

Gail Cornwall for The Hechinger Report

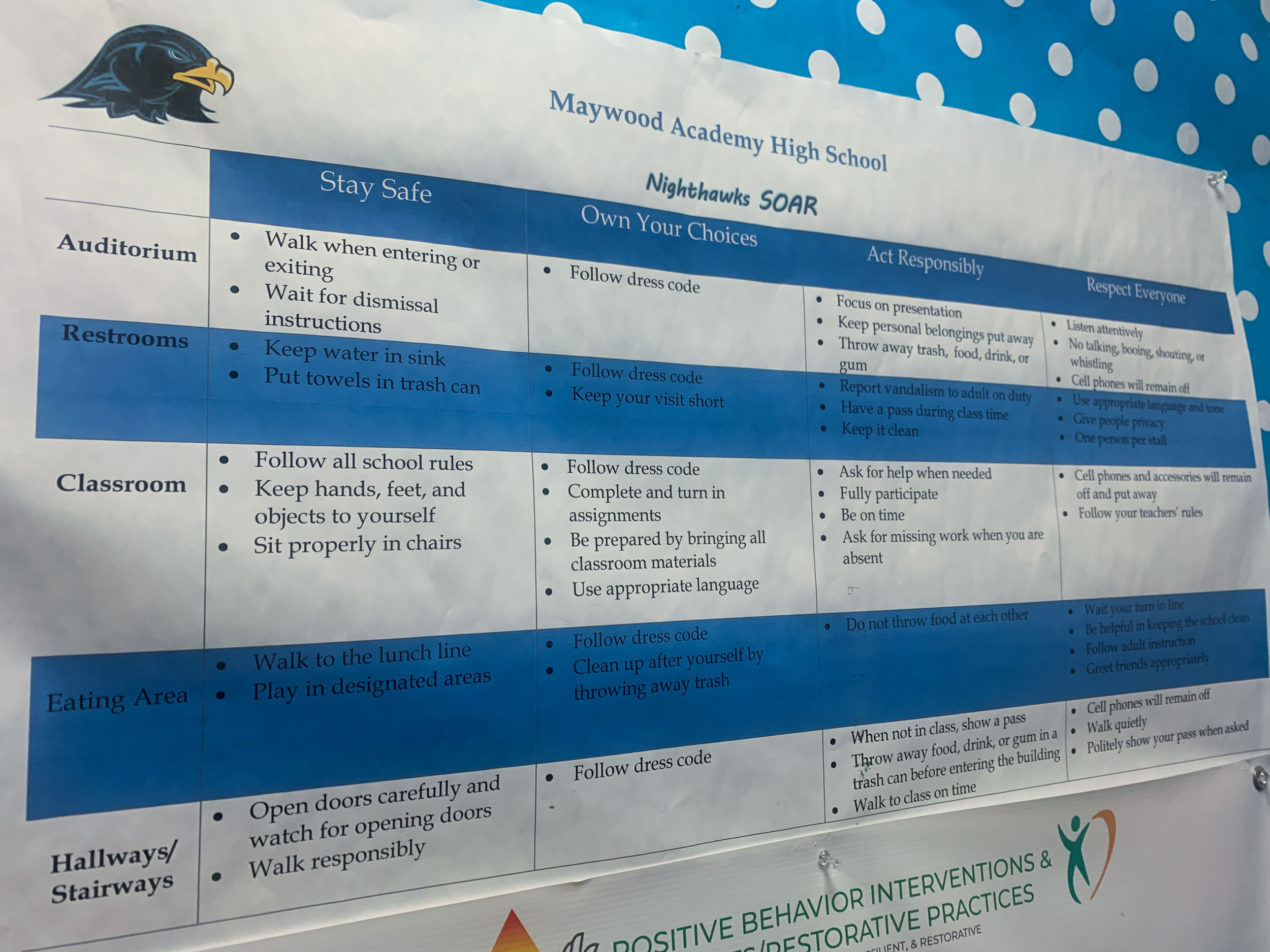

LAUSD’s office of Positive Behavior Interventions & Support/Restorative Practices works with schools to develop and implement behavioral expectations.

Last year, for example, when he asked a student who was late to get a tardy slip, she refused. She also refused when a campus aide, and then the restorative justice coordinator and then the principal, asked her to go to the school’s office. The situation was eventually resolved after her basketball coach arrived, but van der Fluit said it had been “a 20-minute thing, and I’m trying to teach in between all of this stuff.”

That sort of scene is rare at Maywood, van der Fluit said, but it happens. There are students “who just want to disrupt, and they know how to manipulate and control and are gaslighting and deflecting.” He described seeing a student with his phone out. When van der Fluit said, “You had your phone out,” the student denied it. Van der Fluit said there are days he feels “the district doesn’t have my back” under this new system. Researchers, legislators and school board members, he said, wear “rose-colored glasses.”

Gail Cornwall for The Hechinger Report

Critics warned that eliminating suspensions for “willful defiance” would render schools more chaotic and less effective, but Maywood Academy High School is calmer than it used to be, according to teachers and principal Maricella Garcia.

His concerns are not uncommon. But according to Losen, in LAUSD, “The main issue for teachers was that the teacher training was phased in while the policy change was not.”

In recent years there has been some parental pushback too: At a November 2023 meeting of the school district safety and climate committee, for example, a handful of parents described their kids’ schools as “out of control” and decried a “rampant lack of discipline.”

Ortiz Franklin acknowledged an uptick in behavioral incidents over the last three years, but attributed it to the pandemic and students’ isolation and loss, not the shift in disciplinary approach. Groups like Students Deserve, a youth-led, grassroots nonprofit, have urged LAUSD to hold the line on its positive, restorative approach.

[Related: Giving first-time juvenile offenders avenues away from detention in New York]

“Our schools are not an uncontrollable, violent, off-the-wall place. They’re a place with kids who are dealing with an unprecedented level of trauma and need an unprecedented level of support,” said W. Joseph Williams, the group’s director.

District survey data presented at the same November meeting, meanwhile, suggests most teachers remain relatively committed to the policies: On a 1 to 4 scale, teachers rated their support for restorative practices at around a 3, on average, and principals rated it close to a 4.

Even van der Fluit, who maintains that the new way takes more work, said: “But is it the better thing for the student? For sure.”

“And what’s the point in a school if there’s no corrections, just instant punishment?”

Mikey Valladares, 12th grader,

Maywood Academy High School

At Maywood, Marcus Van, the restorative justice coordinator who met with Valladares after the teen argued with a teacher, said students have a chance to talk out their problems and grievances and resolve them. In contrast, Van said, “When you just suspend someone, you do not go through the process of reconciliation.”

Often, so-called defiant behavior is spurred by some larger issue, he said: “Maybe somebody has parents who are on drugs [or] abusive, maybe they have housing insecurity, maybe they have food insecurity, maybe they’re being bullied.” He added: “I think people want an easy fix for a complicated problem.”

Valladares, for his part, knows some people think suspensions breed school safety. But he said he feels safer — and behaves in a way that’s safer for others — when “I’m able to voice how I feel.”

Twelfth grader Yaretzy Ferreira said: “I feel like they actually hear us out, instead of just cutting us out.”

Her first year and a half at Maywood, she was “really hyper sassy,” according to Van. But, Ferreira recalled, that changed after Van invited her mom and a translator to a meeting: “He was like, ‘Your daughter did this, this, this, but we’re not here to get her in trouble. We’re here to help.’” Now, the only reason she ends up in Van’s office is for a water or a snack.

Gail Cornwall for The Hechinger Report

LAUSD’s office of Positive Behavior Interventions & Support/Restorative Practices falls under the “joy and wellness” pillar of the district’s strategic plan. Information pushed out by the PBIS/RP office aims to help students and staff connect in a positive, forward-looking manner.

Van der Fluit said the new approach is better for all kids, not just those with a history of defiance. For example, the class that watched the tardy slip interaction unfold saw adults model how to successfully manage frustration and de-escalate a situation. “That’s incredibly valuable,” he said, “more valuable than learning photosynthesis.”

The Maywood campus is calmer than it used to be, educators at the school say. Students, for the most part, no longer roam the halls during class time. There’s less profanity, said history teacher Michael Melendez. Things are going “just fine” without willful defiance suspensions, he said.

Nationally, researchers have come to a similar conclusion: A 2023 report from the Learning Policy Institute, based on data for about 2 million California students, concluded that exposure to restorative practices improved academic achievement, behavior and school safety. A 2023 study on restorative programs in Chicago Public Schools, conducted by the University of Chicago Education Lab, found positive changes in how students viewed their schools, their in-school safety and their sense of belonging.

In Los Angeles, many students say the hard work of transitioning to a new disciplinary approach is worth it.

“We’re still kids in a way. We are growing, but there’s still corrections to be made,” said Valladares. “And what’s the point in a school if there’s no corrections, just instant punishment?”

***

Gail Cornwall, a San Francisco-based award-winning, freelance writer, is a former ninth-grade public school teacher and higher education lawyer. Her articles on education, parenting and other topics impacting children and families have been published by the Atlantic, Boston Globe, Guardian, the LA Times, New York Times, Salon, San Francisco Chronicle, USA Today, U.S. News & World Report, and the Washington Post, among others.

The Hechinger Report is a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

This story also appeared in USA TODAY.