When California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a budget measure last summer that would increase the financial support provided to older youth and young adults in the state’s foster care system, it felt like a miracle. Less than a year later, Newsom proposed a 2024-25 budget completely eliminating that essential increase in funding for housing and other support services, saying he aims to trim the state’s financial deficit.

Newsom’s plan to cut that $18.8 million of rental and health care subsidies — federal funds constitute roughly a quarter of those dollars — would put more than 3,000 18- to 21-year-olds in foster care at increased risk for homelessness.

Yet, a variety of state and federal laws obligate the state and California’s counties to provide housing and such supportive services as Medicaid-funded mental health and other health care to older foster care youth and young adults. The failure to meet those obligations results in too many youth experiencing extended periods of homelessness or being forced to move into substandard housing, typically far from their support system.

[Related: Gas, food, lodging for homeless students in jeopardy as funding deadline looms]

Common sense and scientific research confirm that people entering adulthood require ongoing support, and it’s widely understood that parents don’t stop caring for their children at age 18. Many young people in foster care have experienced the trauma of being separated from their families and losing social ties, and have often experienced additional trauma while in foster care. Recognizing those realities, in 2010, California lawmakers extended foster care services to young people up to age 21, with the law taking effect in 2012.

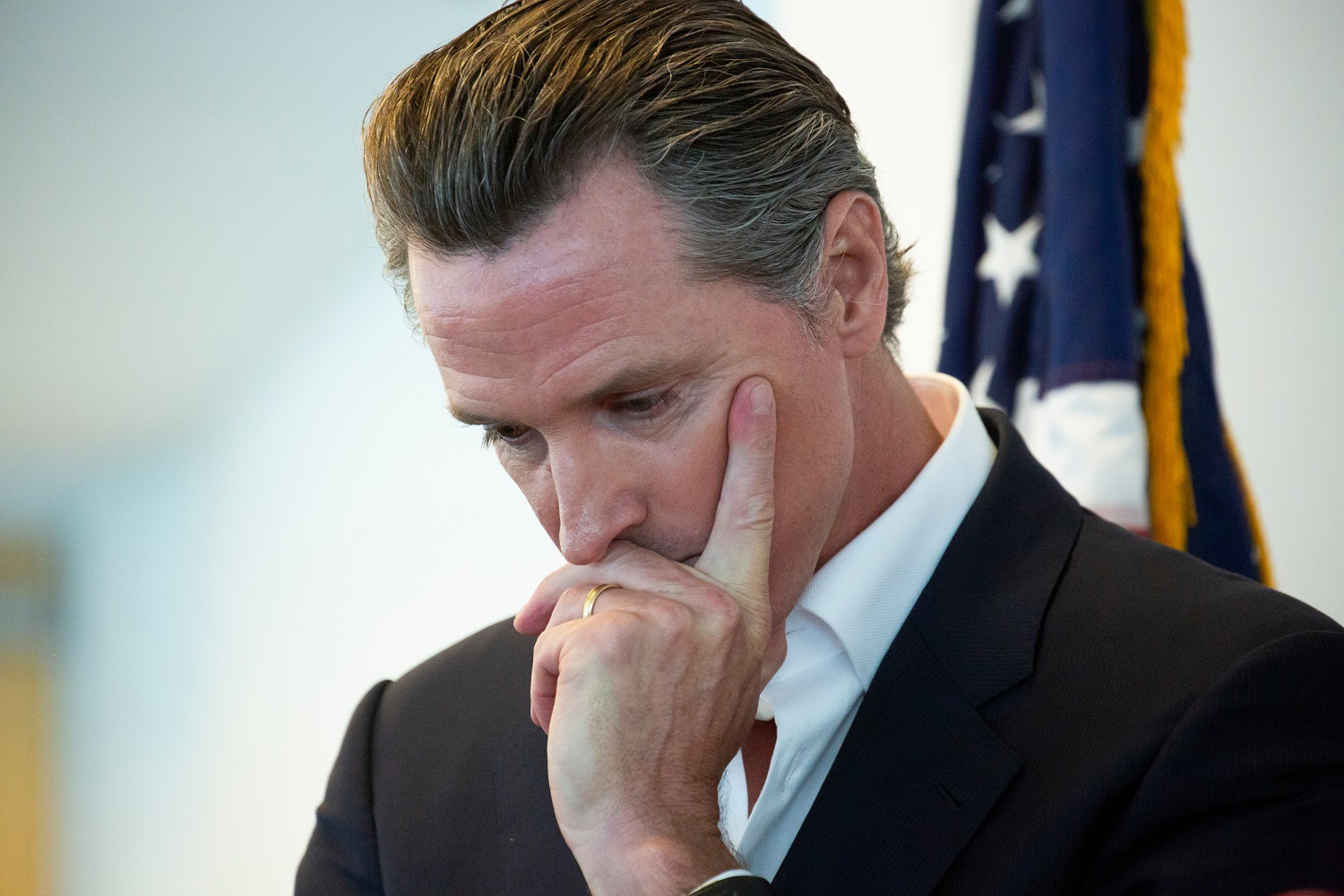

Courtesy of Mara Ziegler

Mara Ziegler

Currently, about 40% of those aged 18 to 21 are placed in what’s called supervised independent living, where youths find someone willing to rent them a room or shared apartment. Once a local child welfare agency caseworker approves the proposed living arrangement, youth receive a monthly stipend of $1,206 to cover all basic living expenses. That amount does not increase, even if the cost of room and board exceeds the stipend. According to private firm Zillow, in March 2024, the median monthly rent in California was $2,941 but as high as $3,795 in the San Jose area, home to Silicon Valley and tech workers whose higher salaries and housing demands have displaced so many longtime residents. (The most recent available Census data put average California rent at $1,870 a month in 2022.)

Because the state’s current rental subsidies are barely half the market rate of rentals in some markets, many of my clients have no choice but to move out of county or even out of state. This has particularly dire consequences for the more than 1,000 custodial parents who are in foster care — let alone those who have, tragically, lost custody of their children for not navigating that difficult system while addressing the trauma that brought them into care in the first place. So, their children become part of another generation entering foster care.

For those young parents who must relocate, moving away often means being separated from the baby’s other parent, their community, job or school. Too often, those become a barrier, either temporarily or over the long term, to eventually being reunited with their kin. The current, insufficient stipend forces too many youths into homelessness or into, as one youth recently reported, a roach-infested apartment, paying rent to a landlord who refused to exterminate the property. Her child has asthma, which can be worsened by roach allergens. It took her more than three months to find a new apartment.

Eliminating the previously approved foster care rent and support services subsidies would needlessly derail the progress California has made toward the governor’s prior commitment to work to prevent youth homelessness. Without housing, many of my clients go into survival mode. Much of their energy is consumed by their focusing on safety or, as one client told me, finding the least scary municipal bus bench to sleep on at night. Their time is spent addressing the panic that comes with having no stable place to call your home, instead of taking steps to pursue a better future. Forget school attendance, forget vocational training, forget focusing on health and well-being, forget creating a clear path to independence.

For over a decade, I have been helping youth in extended foster care navigate the insanely competitive Los Angeles housing market. and live with the consequences of government’s failure to ensure they are properly housed and supported. I’m alarmed by Newsom’s retreat from what he’d promised.

The state of California should leave intact the increase in housing subsidies not only as a practical mechanism for reducing youth homelessness but also to convey to our youth that their safety, stability and future matter.

***

As a senior social worker for the Children’s Rights Project of Public Counsel, a nationwide nonprofit law firm, Mara Ziegler specializes in serving older youth in foster care.