Courtesy of Emily Rodriguez /The Hechinger Report

The entire Rodriguez family dropped Ashley Rodriguez off for her freshman year at Emory University’s Oxford College this fall.

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION ENDS

While affirmative action made strides in increasing diversity on college campuses, it fell far short of meeting its intended goals. And now that it’s been struck down, CBS Reports teamed up with independent journalist Soledad O’Brien and The Hechinger Report to examine the fog of uncertainty for students and administrators who say the decision threatens to unravel decades of progress.

![]()

WILMINGTON, Del. – A wall of the Rodriguez family home celebrates three seminal events with these words: “A moment in time, changed forever.”

Beneath the inscription, a clock marks the time and dates when three swaddled newborns depicted in large photos entered the world: Ashley, now 19, Emily, 17, and Brianna, 11.

Another “moment in time” occurred last June, one that could change the paths of Emily and Brianna. That’s when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in its landmark case on affirmative action, barring colleges from taking race into consideration as a factor in admission decisions.

The ruling struck down more than 50 years of legal precedent, creating newfound uncertainty for the first class of college applicants to be shaped by the decision – especially for Black and Hispanic students hoping to get into highly competitive colleges that once sought them out.

It also places the Rodriguez sisters on opposite sides of history: Ashley applied to college when schools in many states could still consider race, while Emily can expect no such advantage.

Their parents, Margarita Lopez, 38, and Rafael Rodriguez, 42, are immigrants from Mexico who moved to the United States as teenagers.

Ashley is the first in her family to attend college, a freshman studying child psychology on a full scholarship to prestigious Oxford College of Emory University, where annual estimated costs approached $80,000 this year.

Emily is the middle daughter, a senior and mostly straight-A student at Conrad Schools of Science in Wilmington who wants to become a veterinarian, and who spent most of this fall anxiously awaiting word from her first-choice college, Cornell University.

The impact of the court’s decision on enrollment at hundreds of selective colleges and universities won’t start to become clear until colleges send out offers this spring and release final acceptance figures.

“We definitely feel that this year, the window is narrower for students whose GPA does not tell the full story of their brilliance and the challenges they’ve overcome.”

TeenSHARP co-founder Atnre Alleyne

But many students, counselors and families view this admission cycle as the first test of whether colleges will become less diverse going forward, while cautioning it may take years before a clear pattern emerges. The Hechinger Report contacted more than 40 selective colleges and universities asking for the racial breakdown of those who applied for early decision and were accepted this year.

About half the institutions responded and none provided the requested information. Several said that they would not have such data available even internally until after the admissions cycle wraps up next year. Some have cited advice from legal counsel in declining to release the racial and ethnic composition for the class of 2028.

For the Rodriguez family, higher education has already become a symbol of upward mobility, a life-altering path to meaningful careers and the sort of financial stability that Margarita and Rafael have never known.

College wasn’t a part of their culture, and before last year Rafael and Margarita had no idea how complicated and competitive the landscape would be for their bright, hardworking daughters. Of all U.S. racial or ethnic groups, Hispanic Americans are the least likely to hold a college degree.

“I never even dreamed about a place like Emory, or about all the schools that have really good financial aid,” Margarita said recently. She wouldn’t have looked beyond the local community college and state universities for her daughters if she hadn’t learned about TeenSHARP, a nonprofit that prepares high-performing students from underrepresented backgrounds for higher education.

She immediately signed up Ashley, and later, Emily.

TeenSHARP co-founder Atnre Alleyne, with his wife, Tatiana Poladko, and team of advisers, guided Ashley and Emily through their high school course selection and college essays, while pointing out leadership opportunities and colleges with good track records of offering scholarships.

Emory is one. The school admitted no Black students until 1963, but has aggressively recruited students from underrepresented backgrounds in recent years. Hispanic enrollment had been growing before the Supreme Court’s decision, from 7.5 percent in 2017 to 9.2 percent in 2021. Ashley’s class at Oxford is 15 percent Hispanic.

“I felt like I was right at home here,” Ashley said, shortly after arriving in August. The entire Rodriguez family dropped her off and stayed for a few days until she was settled. “It felt very homey to me,” she said. “Everybody is so welcoming.”

Liz Willen/The Hechinger Report

The Rodriguez family at their home in Wilmington, Delaware, left to right: Mom Margarita, middle daughter Emily, youngest Brianna, father Rafael, with their college adviser, Atnre Alleyne.

Still, Ashley worried about her grades as she adjusted to her new workload. She fielded constant texts and calls from her family, who were adjusting to having her away from home for the first time.

Emily missed her sister terribly – together they’d started their high school’s club for first-generation scholars, helping others navigate college choices. “She has the brain and I like to talk,” Emily joked.

This fall, Emily set her sights on some of the most selective colleges in the country, many of which had terrible track records on diversity even before the Supreme Court’s decision. She approached her search knowing that she was unlikely to get any boost based on her ethnicity.

That makes her angry.

“We have so much history behind us as people of color,” Emily said. “So why would we be put at the same level as somebody whose family has benefited off of the harm done to communities of color?”

Emily also knew she would need a hefty scholarship to attend one of her dream schools; her family can’t afford the tuition, and they’ve been loath to saddle their daughters with loans.

“I don’t think it’s a bad thing if poor whites now benefit from affirmative action.”

Richard Kahlenberg, an author and scholar at Georgetown University

Elite schools like those on Ashley and Emily’s lists are more likely to be filled with wealthy students: Families from the top 0.1 percent are more than twice as likely to get in as other applicants with the same test scores. But such schools also offer the most generous scholarship and aid packages, and Emily and Ashley believed they presented the best shot at a different life from their parents’.

“Ever since I was little, I knew that college was the ticket to break this cycle our family has been in for generations and generations, of not knowing, of not being educated,” Emily said. “And because of that, having to work with their backs instead of their brains.”

That the Rodriguez sisters could even consider top-tier colleges is a credit to their mother.

“I want them to have the opportunity I never had,” Margarita said. “I know that life after education will be easier for them. I don’t want them to be working 12, 14 hours like their dad did.”

Rafael Rodriguez has always worked: first, with livestock as a child in central Mexico and later, in Florida, on an orange farm until the age of 15, with a residential permit. His earnings went toward helping the rest of the family come to the United States and settle in West Grove, Pennsylvania.

Rafael didn’t attend high school because he had to help support his parents and sisters. He now owns a trucking company.

Margarita desperately wanted to go to college, but said her mother did not believe in taking out loans for higher education and refused to sign her financial aid forms.

Instead, she married Rafael a few days after graduating from high school and had Ashley a year later. Emily was born 17 months later. Margarita was thinking of enrolling in community college until Brianna came along six years later. She now helps Rafael with his trucking business while working as a translator.

Courtesy of Emily Rodriguez

Ashley Rodriguez fields calls, Facetime requests and texts from her family while settling in as a freshman at Oxford College of Emory University in Georgia.

Both sisters are keenly aware of the gulf between their lives and their mom’s. In her college essay, Ashley described being “a daughter of two immigrant parents who undertook a dangerous journey from their native Guanajuato, Mexico, to America.”

Emily wrote about how Margarita had violated “every norm of our Mexican community, allowing me to sacrifice my time with family on weekends and in the summer” to attend Saturday leadership trainings with TeenSHARP, as well as college-level courses in epidemiology and health sciences at Brown, Cornell and the University of Delaware.

The pressure Emily feels is both formidable and familiar to the immigrant experience, magnified by the divisive court decision.

Hamza Parker, a senior at Smyrna High School in Delaware, feels it as well. He was at first unsure of whether or not to write about race in his essay, a debate many students have been having.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in his majority decision that race could be invoked only within the context of the applicant’s life story, leaving it up to students to decide if they would use their essays to discuss their race.

Meanwhile, conservative activist Edward Blum, who helped bring the case before the court, has threatened more lawsuits and said he would challenge essays “used to ascertain or provide a benefit based on the applicant’s race.”

“I never even dreamed about a place like Emory, or about all the schools that have really good financial aid.”

Margarita Rodriguez, mother

Hamza wavered at first, then rewrote his essay to describe his family’s move to the United States from Saudi Arabia in sixth grade and the racism he subsequently experienced. He applied early decision to Union College in upstate New York; earlier this month, he learned via email that he did not get in.

Neither Hamza nor his father, Timothy Parker, an engineer, know why, or what role affirmative action played in Union’s decision: Rejections never come with explanations.

Parker hopes his son will now consider an HBCU like the one he attended, Hampton University, in Virginia. He worries that if Hamza ends up at a school where he is clearly in the minority, he could be made to feel as though he doesn’t belong.

[Related: Beyond the Rankings: College Welcome Guide]

“I’m letting it be his choice,” Parker said, noting that Hamza might also feel more comfortable at an HBCU given the nation’s divisive political climate. With the end of affirmative action, he added, “It feels like we are going backwards not forward.”

HBCUs are becoming more competitive after the court’s decision. Chelsea Holley, director of admissions at Spelman College in Atlanta, said Black high schoolers may be choosing HBCUs because they fear further assaults on diversity and inclusion and believe they’ll feel more comfortable on predominantly Black campuses.

Parker is now finishing his applications to Denison University, the University of Maryland, the University of Delaware, and Carleton College. He’s not sure if Hampton will be on his list.

Alleyne, Hamza’s adviser, said that while they will never know if the court’s decision had any impact on Hamza’s rejection from Union, he’s concerned about what it portends for other TeenSHARP seniors.

“There are so many factors at play with every application,” Alleyne said. “We definitely feel that this year, the window is narrower for students whose GPA does not tell the full story of their brilliance and the challenges they’ve overcome.”

“We have so much history behind us as people of color. So why would we be put at the same level as somebody whose family has benefited off of the harm done to communities of color?”

Emily Rodriguez, high school senior

Alleyne is also concerned that scholarships once available for students like Parker are disappearing. Some of the race-based scholarships his students applied for in past years are no longer listed on college websites, he said.

At the same time, there are plenty who believe that the court’s decision was a much-needed correction, including Richard Kahlenberg, an author and scholar at Georgetown University who testified in the case. He argues that the ban will lead to a fairer landscape for low-income students for all races.

Kahlenberg is in favor of using affirmative action based on class instead of race. “I don’t think it’s a bad thing if poor whites now benefit from affirmative action,” Kahlenberg said.

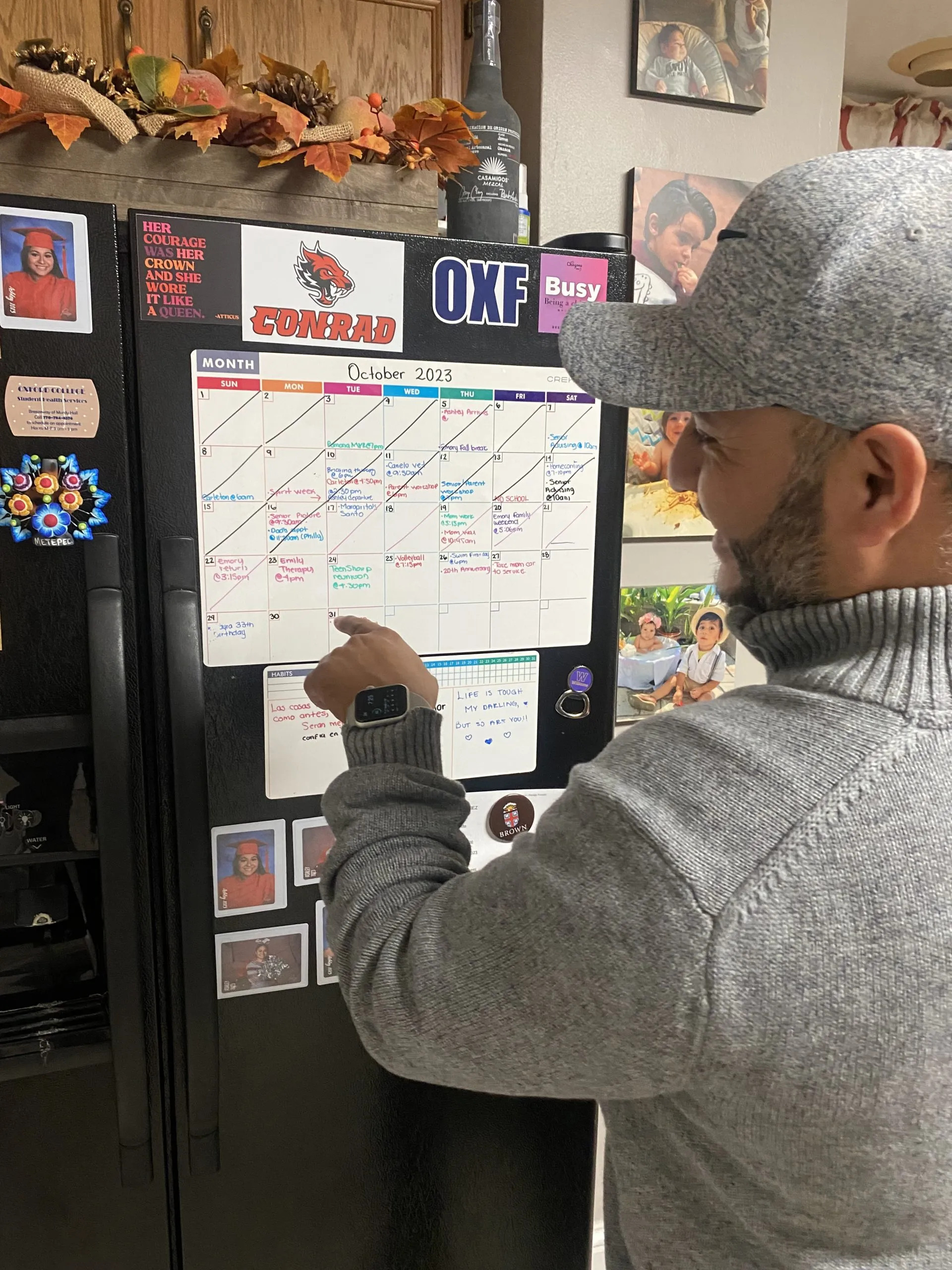

For the Rodriguez family, Cornell’s early decision announcement was long anticipated, to be marked on the magnetic calendar attached to their refrigerator as soon as they knew it. Ashley would be home from Emory for winter break and would hear the news alongside her sister.

For weeks, the family had prepared themselves for bad news: Cornell had announced it was limiting the number of students it would accept early decision, in what the university said was “an effort to increase equity in the admissions process.”

Still, Emily had spent a summer studying at Cornell and gotten to know some faculty and advisers there. She had fallen in love with the animal science program, and the lively upstate New York college town of Ithaca, set amid stunning gorges and waterfalls.

Liz Willen/The Hechinger Report

Rafael Rodriguez, affectionately known as “Papa Bear,” keeps a close eye on the jam-packed family calendar.

“Let’s go, let’s go!” Rafael said as they huddled together in front of Emily’s laptop. Emily wore a white t-shirt with “Cornell” emblazoned in bold red letters on the front, for good luck. She wavered, then clicked.

“Congratulations, you have been admitted to the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences: College major: Animal Science at Cornell University for the fall of 2024. Welcome to the Cornell community!” said the email on her screen, adorned with red confetti.Annual estimated costs for next year would be $92,682 – but Cornell pledged to meet all of it.

Emily screamed, and the room erupted in cheers. Every member of the family began sobbing. Cinnamon, the family’s three-year-old Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, barked wildly.

Emily jumped up and down. “Ivy League!” she shouted. “Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God. I did it.”

Brianna, a sixth grader who will work with TeenSHARP once she’s in high school, hugged both of her sisters.

It will be her turn next.

***

Additional reporting was contributed by Sarah Butrymowicz.

This story about the end of affirmative action is the second in a series of articles accompanying a documentary produced by The Hechinger Report in partnership with Soledad O’Brien Productions, about the impact of the Supreme Court ruling on race-based affirmative action.

Hechinger is an independent, nonprofit news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for our weekly newsletters.