Last summer, staff at La Paloma group homes for teens in foster care began to notice a problem. First, they saw signs of possible drug use in about four boys and confirmed they had used fentanyl. Then a staffer found one boy unresponsive. She quickly administered naloxone kept on site, reviving him, said La Paloma residential clinical supervisor Ed Grove.

Courtesy of Ed Grove

Ed Grove, La Paloma

The Tuscon, Arizona group homes were only caring for about 30 kids at the time, Grove said, so the experience left Grove and the staff shaken up, and they remain on high alert.

“This [fentanyl] epidemic has become such that we don’t have the luxury of thinking that whatever we’ve already done in terms of prevention is enough or completely safeguards our children from being exposed,” Grove said.

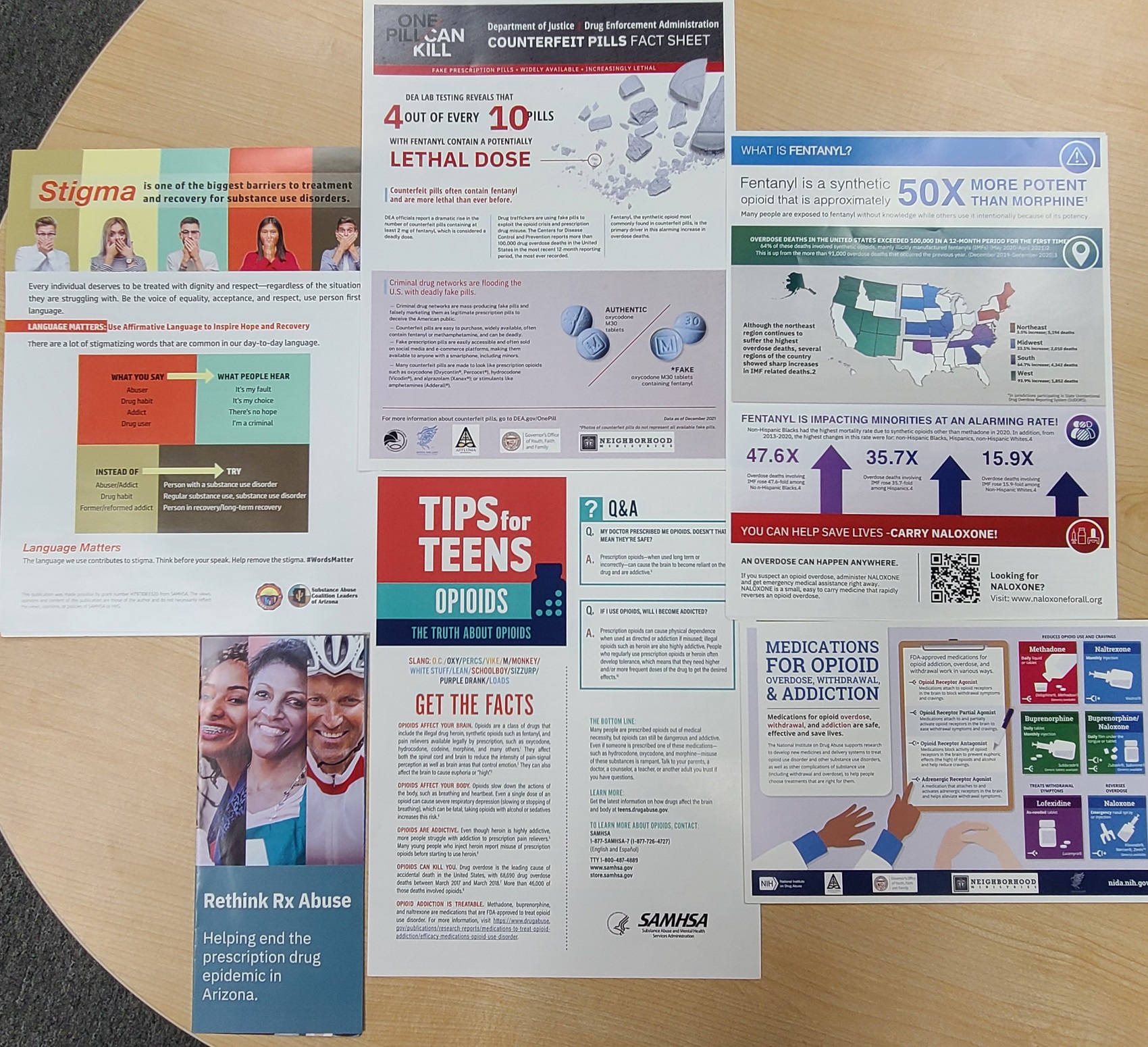

La Paloma has kept naloxone in its group homes since early 2021, but last May the Arizona Department of Child Safety, the state’s child welfare agency, began requiring all group homes, foster family homes, and children’s shelters with kids 12 and older to keep naloxone, the opioid-overdose antidote, on site. (Naloxone is often referred to as Narcan, the brand name for a device that delivers the drug.) The policy also requires foster parents and group home staff to receive training on how to administer naloxone and identify the signs and symptoms of an opioid overdose and to report any use of naloxone.

Arizona is unusual in requiring foster and group homes to keep naloxone on site — an Arizona Department of Child Safety spokesperson said the agency is not aware of other states adopting similar policies before Arizona — but the policy is part of a broader move to keep the opioid overdose reversal drug in places where teenagers are. In recent months, school districts across the country, including Los Angeles, Denver, and Des Moines, Iowa, started stocking campuses with naloxone. Others started years earlier; two districts in Tucson have been keeping naloxone on high school campuses since 2019 or earlier

Drug use in general has been decreasing among teens in recent years, but for those who use, it has become far more deadly, with fentanyl being the prime culprit, according to a 2022 JAMA study. The problem grew even more during the pandemic. During a six-month period in 2019 compared to the same period in 2021, overdose deaths among teens involving fentanyl increased 182%, according to the CDC.

Despite the requirement to report instances of naloxone use, a spokesperson for the Arizona Department of Child Safety said they do not have data at this time on how many times foster parents, group homes, and children’s shelters have used naloxone.

However, in 2021, the most recent year for which Arizona has released data, 44 children in the state died from fentanyl overdoses, out of 863 total child deaths, according to state data. In 2022, four children in foster care died from overdoses, two in group homes, one in a hospital, and one in a shelter, according to the Department of Child Safety’s two most recent semi-annual child welfare reports, though the data doesn’t track whether the overdoses were from opioids or other drugs.

Courtesy of Nancy Williams

Arizona requires foster parents and group home staff to receive training on how to administer naloxone and identify the signs of an opioid overdose.

Fentanyl can be up to 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Other drugs can be laced with fentanyl, making them extremely potent, and users aren’t always aware. Colored fentanyl pills known as “rainbow fentanyl” have also raised concern among experts and caregivers as the candy-like appearance more easily attracts young people who may not know what they’re ingesting.

A large national study from 2018 showed that deaths from opioid overdoses decreased after states enacted naloxone access laws. But there’s little research specifically on substance abuse and overdose prevention among young people in foster care, said Judy Havlicek, a child welfare researcher at the University of Illinois School of Social Work. Most of the data that exists is about young people who have left care. But even then, a paper that Havlicek co-authored in 2014 found that substance abuse was still “poorly understood” among this population.

“I think mental health has been a pretty common topic, but research that really digs down around substance use has been less common, particularly given the risk for exposure to adverse childhood events and trauma,” Havlicek said. “It’s surprising that there is as little research as there is.”

The Arizona Department of Child Safety declined to make an official available to discuss the naloxone policy’s enactment and data collection.

Bryan Samuels, executive director of Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago, a child welfare policy research institute, said without evidence, the Arizona policy might make sense if institutions for all groups of vulnerable populations were requiring naloxone on site, like schools and libraries. But it gets dicey if that isn’t the case, he said.

“It really becomes a question of how specific is the policy to kids in foster care versus a generalized policy around multiple vulnerable populations that are driving that decision,” Samuels said.

Courtesy of Nancy Williams

Nancy Williams, third from right in this photo of her with her husband and children, said many of the foster parents she works with say they feel a sense of relief having naloxone in their homes.

For many in the foster care community in Arizona, the policy was a surprise. Nancy Williams, executive director of the Arizona Association for Foster and Adoptive Parents, said she hadn’t heard about opioid use and overdose being a big issue among youth in foster care, and she wasn’t aware of the policy until it was put in place. She scrambled to inform parents, help them get the required training and find free naloxone to stock their homes. About 850 foster families needed the training in a matter of months, she said.

But Williams said many of the foster parents she works with say they feel a sense of relief having naloxone in their homes, given the risk fentanyl poses not just to their foster children, but all children.

Tracie Hammond, a foster parent in Glendale who is also a group home manager, said she’s never had to use naloxone at home or in her job, nor have any of her staffers. But she’s witnessed a lot of kids struggling with their mental health, especially in the wake of the pandemic.

“When kids are struggling, they tend to look for something to dull the pain. [Fentanyl] is one way they can do that, so it’s always a concern for me,” Hammond said. “Just in case somebody does make a mistake or a bad choice, I feel glad that I have [naloxone] in my home for our neighborhood kiddos or my grandkids or anybody who’s over here.”

***

Colleen Connolly is a Minneapolis-based journalist who covers education and child welfare, among other topics.