MANHATTAN, N.Y. — When Naomi Peña’s first-born child was having trouble reading 16 years ago, teachers at his public school chalked it up to behavior problems.

“They were just labeling my kid as lazy,” said Peña, of Manhattan, whose four children were eventually diagnosed with dyslexia. “I was in a space of not knowing what this thing was.”

Then a young mother on a low civil servant salary with little knowledge of dyslexia, she struggled to get him a diagnosis, which can cost upwards of $10,000, and to lobby for access to targeted reading help tailored toward students with severe reading challenges.

Federal law requires public schools to give students with dyslexia targeted tutoring and extra time on tests. But to get those services, teachers and administrators have to identify and accept potential signs of dyslexia. Peña and other parents say they often need to secure a formal dyslexia diagnosis by a psychologist to ensure they get services or, if public schools aren’t helping, subsidies for private school tuition.

Around 40 states require schools to screen children for risk of dyslexia, according to the National Center on Improving Literacy, a consortium of researchers. But in New York State, finding out if a child is dyslexic is left to the initiative of individual schools and parents.

New York, California and Illinois are among the few states that don’t require schools to routinely test children for potential indications of dyslexia, according to a list maintained by the National Center on Improving Literacy. Those states include the some of the largest school districts, with high percentages of non-white students.

All students in Miami-Dade County Public Schools, for example, are tested for signs of significant reading difficulty and the district provides comprehensive psychoeducational evaluations for students who show signs of potential dyslexia at no cost to families, said district spokeswoman Ana Rhodes.

Even in Chicago where the state doesn’t mandate testing students for signs of dyslexia, 93% of kindergarten through 2nd grade schools use data from an online reading instruction platform to identify those who show signs of dyslexia, according to Chicago Public Schools spokeswoman Sylvia Barragan. As in Miami, evaluations for students who show potential signs of dyslexia are free.

The stakes are high

The stakes are particularly high for Black boys. Some research suggests boys are more likely to be dyslexic than girls. And Black boys who are dyslexic more likely to be misdiagnosed with conditions like attention deficit disorder and behavioral disorders.

Cedar Attanasio/For Youth Today

Naomi Peña is a co-founder of the Literacy Academy Collective, a grant-backed organization that’s involved in New York City’s pilot program.

That can set them up for failure. Students with dyslexia respond well to early interventions, educators say. But if students don’t get help by fourth grade, reading challenges start to compound. Students who can’t read quickly and with joy take in less information, and their confidence can spiral downward, educators say.

Peña said her son’s elementary school slow-walked his at-risk testing, his intervention, and his diagnosis, taking months to complete the process. She ultimately paid for him to be diagnosed herself.

“I was just told he was having trouble reading. He was being disruptive,” she said.

By middle school Peña’s eldest son, who is Latino, was so behind that doing poorly in school was starting to become part of his identity.

“He was so far behind academically that he ended up gravitating to kids who were completely disengaged from school,” Peña said.

He barely graduated and now, at 22, isn’t considering college, she said.

“The truth is 15 years later he’s not fine; none of it worked,” Peña said.

Pilot program could change the trajectory

A pilot program in New York City public schools could change the trajectory for some New York City children.

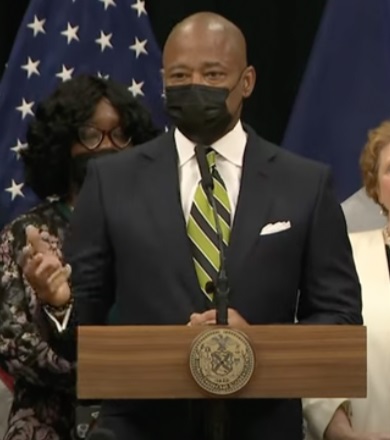

New York City Mayor Eric Adams, who often spoke of his long-undiagnosed dyslexia and resulting struggles in school on the campaign trail, announced in May ambitious plans to create “the largest, most comprehensive approach to supporting public school students with dyslexia in the United States.” The pledge included screening all students in the city for dyslexia risk, more training for teachers and the creation of a school specializing in educating dyslexic students.

Delivering on those promises, as schools in New York and across the country face the challenge of students who are already struggling academically due to the pandemic, is off to a slow but significant start.

But if Adams’ pledges become reality, they could help the nation’s largest school district catch up with much of the rest of the country; and put more Black and Hispanic boys on track for success in school and life.

“I need to do something different”

In 2019, frustrated New York City parents banded together to create the first and only public school in the city centered around serving students with dyslexia, Bridge Preparatory Charter School on Staten Island.

In January, Mayor Adams pledged to create at least one more school specifically serving students with dyslexia by 2023 and eventually one in each of the city’s five boroughs. The city is currently “looking at options” for designing, constructing and staffing those schools, said Department of Education spokeswoman Nicole Brownstein.

New York City Mayor’s Office/Via You Tube

New York City Mayor Eric Adams announced in May ambitious plans to create “the largest, most comprehensive approach to supporting public school students with dyslexia in the United States.”

And as part of a pilot project, begun in fall 2022, 160 of the city’s 700 elementary schools have been evaluating the reading abilities of first- through third-graders to identify those at-risk for dyslexia. The schools have also made changes to how they teach all readers, and how they intervene with struggling readers.

New York City Public Schools Literacy Collaborative Executive Director Jason Bourges believes that early intervention in the pilot program can help many kids on the dyslexia spectrum without requiring a diagnosis or a special education classification.

But he’s trying to temper expectations for the pilot program.

“We’re not going to go out and start screening for risk with every single student in New York City public schools this year,” Bourges said. “We’re going to be doing it [at a] subset of schools and then scale over time.”

“We’re really going to be offering more support in more areas where our children possibly, historically were not getting that specified support in dyslexia,” said Yael Leopold, principal of Public School 125 in Harlem, one of the pilot schools.

Starting this year, parents in the pilot program schools will be notified if their child is at risk for dyslexia. That would immediately qualify them for some additional reading help from a reading specialist.

Bourges said that early interventions can give students the tools they need to learn how to read, even if they have dyslexia-like symptoms, and even if they’re not diagnosed.

Most schools in the city already teach reading through phonics, which since the late 1990s has been seen as the most effective teaching method for all readers, including those with dyslexia. But all of the pilot schools will go farther than most other schools by training teachers in phonics and requiring phonics instruction in the classroom.

Students in the pilot program schools who struggle with reading will also receive regular reading tutoring, either one-on-one or in small groups.

“Most students, it’s only five times of interaction with practice and they begin to map the words by memory,” said Bourges, the literacy director, but children with severe dyslexia, including overlap with attention and phonological disorders “need up to 30 times more practice in word reading development.”

Some of the pilot program’s changes were already integrated into the curriculum last year at Public School 125. That’s already led to a “dramatic mindset shift” among teachers, said Leopold, the principal.

Leopold said teachers told her “This is the first time that I’ve said, ‘I need to do something different,’ versus it being that the child needs to do something different.”

Diagnosing dyslexia

Dyslexia is hard to spot in young children because the symptoms, like avoiding reading, can overlap with not being able to focus. Like illiterate adults, children can also fake reading by memorizing words based on context. Sometimes it takes testing, including the use of “nonsense” words that can’t be understood contextually, to see if a child can read or not.

Estimates of how many children are dyslexic range from as low as single digits and as high as 17%. Few of those studies track the severity of dyslexia, which can range on a spectrum from slow reading to no reading at all.

“The screening is good, this is something we should be doing,” said Rachel Fish, an education sociologist at the New York University Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development who studies how students are sorted into special and gifted education programs, of New York City’s pilot program.

Fish’s research has built on earlier studies showing that Black boys are disadvantaged by racial bias in the process of screening for educational disabilities.

Fish’s research suggests that Black boys are more likely to be diagnosed with a behavioral disorder, compared to white boys. That’s especially true if they attend a predominantly white school. White students with dyslexia are more likely to be diagnosed with dyslexia, and to get more academic help and therapy for speech impairments that sometimes accompany dyslexia.

For parents, sussing out the possibility of dyslexia from often overlapping disabilities like ADHD or vision problems takes time and money. A definitive diagnosis requires a battery of tests performed over as long as a week and costing parents upwards of $10,000.

Peña, a co-founder of the Literacy Academy Collective, a grant-backed organization that’s involved in the pilot program, eventually learned all four of her children were dyslexic, after paying herself for their testing.

Three of her dyslexic children are still school-aged. One attends a private school; two attend a public district school. At the private school she pays around $70,000 in tuition. She believes she’ll be reimbursed by the city after two years, but isn’t absolutely sure. She said the city offers direct reimbursements, but it would have delayed enrollment by a year or more.

A step forward

As it stands now, the pilot falls short of Adams’ pledge “to screen all New York City students for dyslexia and give them the support they need.”

Yet some advocates across New York State say it’s a step forward for the city and could serve as a template for lawmakers in Albany.

“New York is lucky; they have this wonderful mayor,” said Helen Roussel, Executive Director of the Dyslexia Advocacy Action Group and mother of a dyslexic son in suburban Long Island, east of New York City. Adams’ advocacy on dyslexia has inspired her in her own advocacy work, she said, and contrasts sharply with what she hears from schools outside of New York City.

With Adams driving the agenda, literacy advocates are hoping they can cement the importance of phonics-based reading instruction, as well as assessments and data gathering on student performance to identify students who are struggling and get them get extra help.

However, Gov. Kathy Hochul recently vetoed a bill that would have convened a panel to recommend best practices in dyslexia screening and teacher training and other reforms. Hochul’s office did not respond to requests for comment about her veto.

Roussel had hoped the work of such a panel would have yielded, for students statewide, screening and targeting teaching similar to what’s happening in New York City.

“We are certainly not leading on the issue, by any account. There’s no screening of children,” said bill sponsor State Sen. Brad Hoylman, of Manhattan, whose daughter is dyslexic. “I noticed personally because although my now-11-year-old was screened for vision — which was very important, because we didn’t know that she was farsighted — she wasn’t screened for dyslexia, and we had to figure it out ourselves.”

***

Cedar Attanasio is a New York City-based journalist who covers the intersections of youth, nature, and immigration.

***

This story was corrected on Dec. 16, 2022: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Naomi Peña’s eldest son is Black. He is Latino. The earlier version also incorrectly stated that three of Peña’s children attended both charter and private schools. One child attends a private school; two other children attend a district public school.