After 17 students and teachers were shot dead at a Florida school 23 miles away from her hometown, Ashley Freeland was afraid to step back inside her own classrooms.

Student Ashley Freeland raised money for her school’s Stop-the-Bleed kits.

“I was terrified to go to school the next day,” Freeland said, of that 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High in Parkland. “And my parents were, like, ‘Ashley, you’ll be fine, you’ll be safe, just go to school.’ And I did. But I was scared to go and I know a lot of my friends were scared to go.

“You don’t know where it’s going to happen next. And you don’t know who it’s going to happen to.”

Persuaded by that reality, Freeland raised $15,000 to outfit every class at 4,800-student Cypress Bay High School in Weston, Florida, with kits from the American College of Surgeons Stop the Bleed campaign. The campaign, which bears the name of a pre-existing U.S. Department of Defense program, trains everyday people in how to stanch gunshots and other types of wounds.

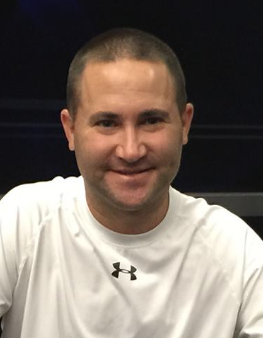

Courtesy of Paul Gorlick

Teacher Paul Gorlick, advisor to Make Our Schools Safe chapter at Cypress Bay High.

Last August, teachers and other school staff at Cypress Bay joined what the surgeon’s group says are more than 2.4 million people who have completed that training. Among them is Paul Gorlick, a social sciences teacher and advisor to Cypress Bay’s Make Our Schools Safe chapter, which Freeland, a senior, launched.

That these times call for such training has been hard for some to accept, Gorlick said. Teachers flinched at the idea of being trained to triage gunshot wounds until they realized those new skills also could be used to lessen other injuries.

“Everybody who did [train] said positive things about it. They feel a little more at ease and comfortable if they ever had to use what was in the kit,” he added. “The kids are aware of the kits in every classroom. They understand that it’s not just for a bullet wound. It could be for any type of serious wound.”

First moments after a shooting are critical

During those first crucial moments after a catastrophic accident or calculated gun violence, the reaction of nearby individuals can mean the difference between life and death for a person with a severe bleeding wound or injury.

Dr. Shane Speights, dean of the NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine in Jonesboro, Arkansas.

“If someone has an acute blood loss — let’s say there is the severing of an artery — by and large, that person will bleed out before the ambulance can make it there,” said Dr. Shane Speights, dean of the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine campus in Jonesboro, Arkansas.

Speights said third-year students at the osteopathic medical school, housed at Arkansas State University, are trained to stop bleeding. Upon completion of the training, the medical students get kits containing bandages and tourniquets that they can keep.

“We’ve had students use these,” Speights said. “So they go out in the community and stop at a car accident, and they’ve broken into this pack and used it to help control bleeding … We have our students providing care, providing meaningful trauma care before they even graduate from medical school.”

Alongside Arkansas, where the Department of Health has been equipping high schools statewide with tourniquets and providing training, others among a growing number of states requiring training and/or gunshot trauma kits in schools or other public places are Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas.

Most recently, in September, California lawmakers enacted a law requiring emergency trauma kits in newly constructed public or private buildings throughout the state. In the U.S. Senate, a bipartisan bill proposes funding to help states expand access to bleeding control kits in public places.

In Missouri, during the 2022 legislative session, a measure requiring bleeding control kits in all public and charter classrooms statewide was introduced.

Dr. Doug Schuerer, trauma services director at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

“We as trauma surgeons are huge advocates for Stop the Bleed. It’s been legislation in Missouri the last two years and hasn’t made it across the finish line,” said Dr. Douglas Schuerer, a trauma surgeon at Barnes-Jewish Washington University in St. Louis.

“There are a lot of schools already doing it and some universities that already have it,” added Schuerer, also vice chair of advocacy for the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. “We would love to make it a statewide thing.”

Recently, St. Louis became the site of the nation’s 40th active school shooter incident of 2022. A 2021 graduate of Central Visual and Performing Arts High killed a 15-year-0ld student and one teacher; five other students were wounded by gunfire or injured in the ensuing chaos before St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department officers shot and killed the 19-year-old gunman.

Some districts already were binding wounds

Ladue School District in suburban St. Louis began training all school nurses to treat severe wounds several years ago, with the understanding that the skills likely would be used for traumas other than gunshot wounds, including ones that might occur in the school district’s family and consumer sciences classes.

Nurse Ann Body of Ladue School District in Missouri,

“They’re cooking, they’re using sharp knives. We have students who are using box cutters for craft projects. We have students who take woodworking classes and are using saws and drills and those kinds of heavy machinery,” said Ann Body, the district’s lead nurse, noting potential injuries from the school bus or other accidents, too.

“ … Like CPR [cardiopulmonary resuscitation], it’s a very good life skill to have in the event of an emergency.”

Ladue school employees were trained by Mercy Hospital St. Louis, where emergency care nurse and trauma educator William Downum teaches stop-the-bleed courses. Downum also has trained high school students in health occupations classes, police officers, members of gun clubs and church groups and other individuals.

[Related story “Listening for gunshot victims’ ‘audible blood,’ then stopping its flow“]

The free in-person training or the free 90-minute online course caution trainees to, first, call 911 and make sure the environment is safe enough for them to begin to try to stop bleeding. The training itself shows people how to control or stop bleeding by applying hand pressure to a wound, packing a wound with an absorbent material or applying a tourniquet.

William Downum, a Mercy Hospital St. Louis emergency care nurse and trauma educator.

The training is free. The trauma kits cost. Those sold online carry varying price tags, including $69, $99 or more. For example, a $109 kit, sold by the American Red Cross, includes a container pouch, tourniquets, gauze, material designed to trigger blood clotting, trauma sheers and rubber gloves.

Downum said he tells trainees who want to make their own kits which essentials to obtain.

“You need more than one tourniquet, you know, just for a family,” Downum said. “And if they shop around, they can find all the things that are in that kit and put it together in a baggie … and save quite a few dollars like that.”

Overcoming fear by being proactive

Freeland, the Florida student, said she doesn’t want anyone at Cypress Bay High to be paralyzed by their fears of being shot at school.

After Parkland, what helped Freeland channel her own fears into action was meeting Lori Alhadeff, mom of 14-year-old Alyssa Alhadeff who was killed at Margory Stoneman Douglas. “I knew that was my chance to make a difference in my community,” Freeland said, of learning about how Lori and her husband Ilan Alhadef co-founded Make Our Schools Safe.

Courtesy of Lore Alhadeff

Lore Alhadeff, co-founder of Make Our Schools Safe

It advocates for Alyssa’s Law, which requires schools to install silent panic alarms directly linked schools to law enforcement agencies. The Alhadefs are among those who say they believe that signal would shorten the amount of time it takes for officers to get to the scene, subdue the threat and triage victims. Alyssa’s Law passed in New Jersey in 2019, Florida in 2020 and New York in 2022. Similar legislation has been introduced in Arizona, Nebraska, Virginia and Texas.

In Weston, Florida, Freeland said she has not yet been trained to treat severe wounds. But she expects to do so, with other student members of Make Our Schools Safe.

“It’s not something that’s easy to deal with for anyone,” said Freeland, the Florida student, “whether you live in the city, whether you live in the country, whether you are a citizen of the United States.

“I’ve never experienced actually being at the school where it happened but … my advice is, ‘If you want to see a change, be the change.’”

***

Award-winning health journalist Sandra Jordan’s byline has appeared in, among other publications, the St. Louis American, where she also was an assistant managing editor. Previously, she was a producer for TV newsrooms in Kansas and Missouri.