CHICAGO — In a cavernous room at the local electricians union headquarters, dozens of high school students and recent graduates are starting their first day of an intensive, two-week solar energy program that will end with them working in a real job for nearby contractors.

Among them is Santino Ruvalcaba, an 18-year-old resident of Chicago’s Little Village, a working class Latino neighborhood that has suffered the effects of environmental racism — from bad air quality to low life expectancy compared to more affluent, whiter neighborhoods in the nation’s third densest city.

But for Ruvalcaba, a recent high school graduate, it was the hands-on nature of the work and the chance to live a better life than his parents that spurred him to join the program.

Michael Gerstein/For Youth Today

High school students and recent graduates gathered in a Chicago IBEW hall in August for an intensive, two-week solar energy job training program.

“[My mom] always wanted to be a teacher, but she couldn’t because of the money for college,” Ruvalcaba said.“My dad, he’s a manager for a warehouse, so most of his paycheck money goes to rent and stuff. So it’s not that much, but it still keeps us afloat.

“I’ll have a lot more to work with,” he continued. “Whatever benefits me benefits them — that’s how I see it.”

The two-week solar academy is geared toward Chicago youth and run by Chicago’s branch of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, IBEW Local 134, using funds from 2016 state climate legislation. It draws students and recent graduates from a handful of schools across Chicago, some of which have started their own solar training programs in partnership with the union.

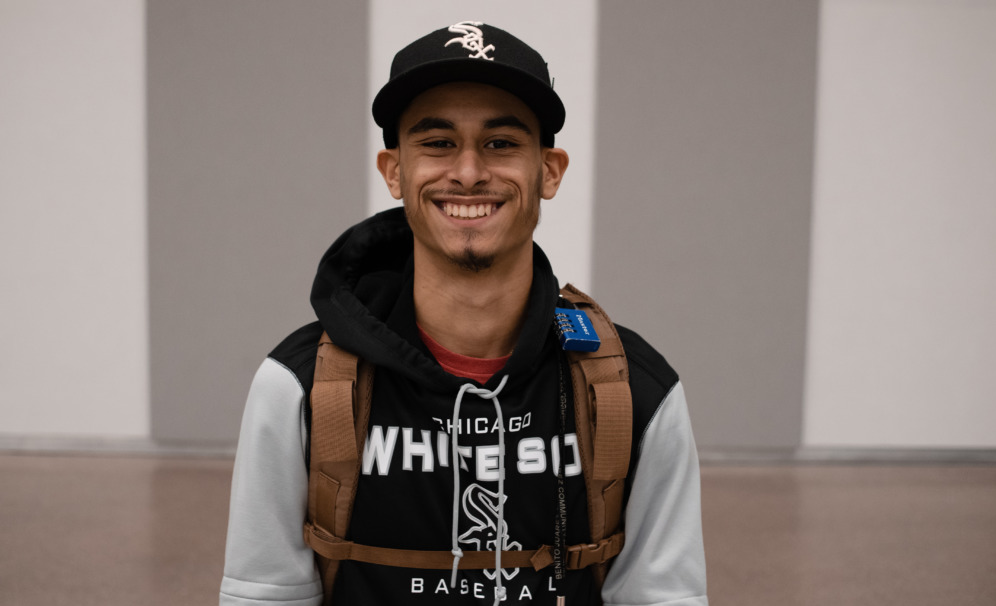

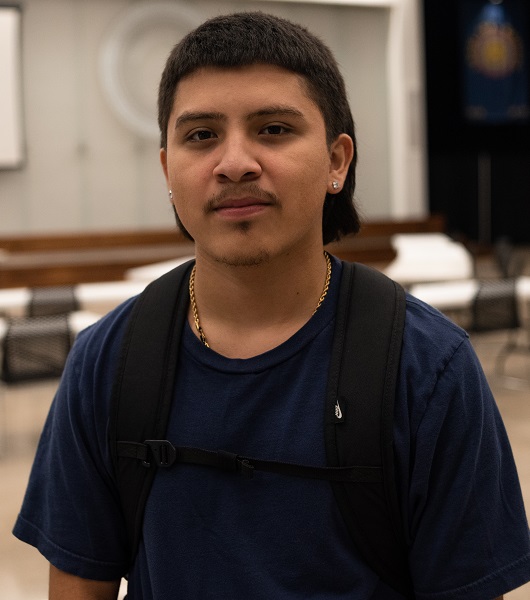

Michael Gerstein/Youth Today

Santino Ruvalcaba, an 18-year-old resident of Chicago’s Little Village, said the hands-on nature of the work and the chance to live a better life than his parents spurred him to join the solar energy job training program.

Students who take part in the solar academy learn the basic principles of electricity and how to put together circuits. Eventually they learn to install a full-size, 285-watt solar module. After completing the program, they have the opportunity to get placed in a contract solar job and are considered “pre-apprentice” electricians, on track to become apprentice-level electricians and then full electricians.

Advocates say programs like these are necessary, not only to meet Illinois’ own ambitious climate goals, but to help thwart the disastrous consequences of global temperatures climbing more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-Industrial levels.

For students like Ruvalcaba in the city’s working-class Lower West Side, where 24% of the population has a college degree and where the median household income is just under $60,000, the solar academy is a direct path to a well-paying and secure job. After five years of earning about $20 an hour, with raises every six months, they’ll be qualified to work in a career in which they could earn up to $50 an hour plus substantial benefits and a comfortable retirement as a union electrician.

“I need money versus an education,” said Eric Camerena, 19, explaining his decision to enroll in the solar program.

Related stories

• What are green jobs and how can I get one? 5 questions answered about clean energy careers

• After a win for U.S. climate change education, classroom implementation is off to a slow start

• Youth find hope restoring Rio Grande wetlands threatened by climate change

• Youth and climate change: How a generation is adapting while fighting for their future

“I’m probably gonna be the one who’s making the most from my career, because I’ve always been surrounded by hard work,” Camerena said. “If I do everything correctly, I’ll be able to give back to my family.”

Most young people who enroll in these programs are drawn by the promise of a good job and a hands-on class that gets them away from textbooks, said James Klock, a solar instructor at Benito Juarez Academy, a public school in the predominantly Latino neighborhood of Pilson on the south side of Chicago that has embraced solar technical education.

But Klock, a former math and science teacher, said students leave his class with “a clear understanding of how climate change is happening, and what the role that the work they’re trying to do has relative to that.”

Illinois has set a goal of generating 40% of its electricity with renewable energy by 2030. To accomplish that, the state will need a lot more workers, and a lot more workers from neighborhoods like Pilson and Little Village, said John Delury, senior regional director for Vote Solar, a group that advocates for clean energy.

“There’s definitely a very, very high demand for workers right now,” Delury said. “We’re just not keeping pace.”

The total number of solar jobs nationally has doubled since 2011 to more than 255,000, and industry experts say it will keep growing thanks to the recently-signed Inflation Reduction Act, the government’s biggest climate package to date, which includes incentives for renewable energy.

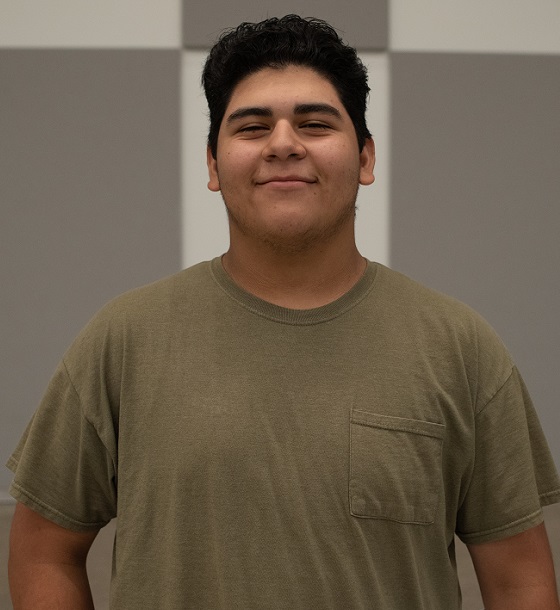

Michael Gerstein/Youth Today

Isaiah Zargoza, 19, a graduate of Benito Juarez Academy who grew up in Little Village, saw the solar job training as a chance to have a better life.

Twenty-two states and the District of Columbia have set decarbonization goals — renewable energy quotas that aim to eventually move away from fossil fuels.

In addition to setting renewable energy benchmarks, Illinois is also requiring that 30% of the labor force in this field come from backgrounds that have borne the brunt of environmental racism or face other barriers to working in the field.

Mijin Cha, an urban environmental policy professor at the Occidental College in Los Angeles, said renewable energy transitions must protect workers and communities that might rely on fossil fuels for their livelihood.

“We also have to think about the people who have borne the brunt of the fossil fuel economy, but have not had the economic opportunity that comes from it as well,” Cha said.

Illinois lawmakers “really centered that piece,” she said.

Cha lauded high school training programs like the one at Benito Juarez. She said there should be more programs to train incoming workers and help current energy workers learn new skills amid growing demand for renewable energy.

But Delury from Vote Solar worries that the strict requirements to hire from backgrounds that have borne the brunt of environmental racism are now the state’s biggest hurdle in meeting its climate goals because of the labor shortage.

“We don’t yet have the robust pipeline” of qualified workers from impacted communities, he said. “2023 starts to give me indigestion just because of that mismatch.”

Cha argues that the gap itself is evidence of the systemic racism the law is intended to address.

“Why don’t you know how to diversify your workforce?” she said. “I don’t see any way except to just do it. Now’s the time to start creating these pipelines.”

Michael Gerstein/Youth Today

Bob Hattier, IBEW Local 134 Business Representative, leads the union’s renewable energy job training programs.

Since the union’s solar training program launched in 2019, at least 90 young Chicagoans have been trained in the basics of solar energy and placed into pre-apprentice electrical jobs, said Bob Hattier, a business representative with the union and executive director of the Illinois IBEW Renewable Energy Fund.

In 2020, the program was paused due to the coronavirus pandemic before resuming in 2021, when it also expanded the number of participating schools.

“I think we’re gonna continue to need more people, especially as energy goals nationwide are increasing,” Hattier said. “They won’t be out of work.”

Benito Juarez Principal Juan Carlos Ocon said the program has been so successful at his school that he’s trying to expand it. If the district approves his request, it would funnel more Juarez students into the program and allow students from any neighborhood in the city to attend the school for its solar program.

“Our students are immensely talented and they know the jobs we need to prepare them for may not even yet exist, but the skills these jobs require is what we can focus on,” Ocon said. “The solar program is one of those exciting opportunities.”

***

Michael Gerstein is an award-winning freelance journalist based in Chicago. He’s written for the Associated Press, WBEZ (Chicago’s NPR station), The Detroit News, the Santa Fe New Mexican and other news outlets.