Shahrukh Khalibeak, 17, is a force for good.

He and his family arrived in the U.S. in August 2021 after the Taliban seized complete control of Afghanistan. As the oldest of six children, he is not only making the transition to a different school environment, but also working part time, learning to drive, and being the main translator and cultural interpreter for his parents and younger siblings. He has taken on these responsibilities, which challenge his capacities, because of his motivation to help his family.

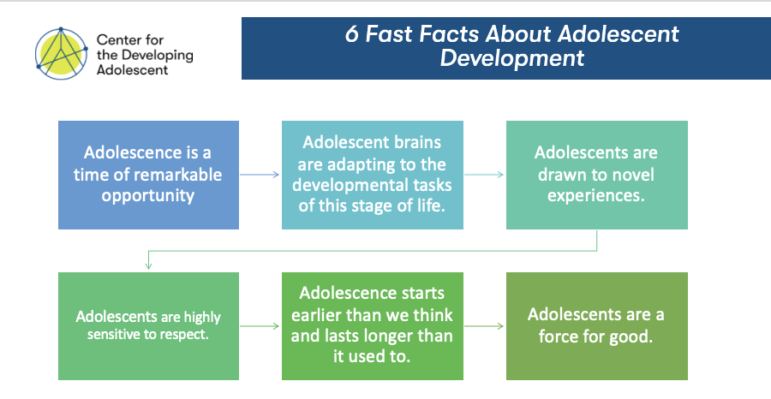

Adolescents are a force for good is one of the UCLA’s Center for the Developing Adolescent six principles of adolescent development. The others are equally declarative.

These simple declarations are powerful discussion starters because they force us to examine embedded assumptions that shape how we interpret adolescents’ behaviors and that in some cases have been reinforced by over-simplification and selective use of the incredibly nuanced research.

These simple declarations are powerful discussion starters because they force us to examine embedded assumptions that shape how we interpret adolescents’ behaviors and that in some cases have been reinforced by over-simplification and selective use of the incredibly nuanced research.

Shahrukh’s level of responsibility is common among immigrants. It is also common among U.S.-born teens whose parents are struggling for any number of reasons. Immigrant youth, even as they struggle to catch up in school, may be given the benefit of the doubt more readily and get more credit for their non-academic contributions to their families. Additionally, the social, educational and financial services and supports available to immigrant families in many communities are better coordinated and less stigmatizing than those in place for resident struggling families.

Shahrukh and Samaya Khalilbeak stand outside Edison Preparatory School, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The district has enrolled more than 300 Afghan students since August, 2021.

The Khalibeak family was welcomed by Catholic Charities, which helped them find housing and jobs. The schools anticipated the children’s needs — providing each with a laptop, supplies and bilingual dictionaries; working closely with parents and students to understand their values and help them navigate school structures, cultures and expectations; and providing supports if behavioral issues begin to surface because of the adjustment pressures.

I know too that Tulsa’s Opportunity Project and Tulsa Public Schools’ collaborative effort to make Tulsa “a city of learning” also provide Tulsa immigrant youth connected opportunities for learning and development.

Last year, I had an opportunity to get to know the story of another amazing immigrant youth.

Margarida Celestino’s family came to Portland, Mainein 2016. Their family, similar to Shahrukh’s, was greeted by a social services agency prepared to help with all aspects of the transition. They were assigned a case worker who helped them get permanent housing, find employment, connect with community resources and enroll in school. Because the case worker took the time to get to know Margarida well enough to be impressed with her intellect and determination to go to college, she made calls to get her into Casco Bay, a public high school that is a part of the EL Education Network. There Margarida was immersed in an intentionally crafted community of adults and students all focused on building character, competence and community.

Margardia graduated as Casco Bay’s valedictorian, a result of her drive as well as a support system of partnerships between the school and other organizations. Margarida names four adults and organizations, beyond teachers and the classroom, that were a part of her support system: her school’s nurse, her school counselor, the Boys and Girls Clubs of Southern Maine program director and the public library’s teen librarian. Her story of the complementary roles they played throughout her high school years was so impressive that we asked her to co-host a series of podcast episodes featuring these local youth champions.

The interviews gave us a unique opportunity to look at a single community’s asset building infrastructure from the bottom up, from the experiences of young people and practitioners. They show how Portland, Maine, much like Tulsa, Oklahoma, has empowered and supported practitioners across systems to work collaboratively to change the odds for the most vulnerable young people in their community.

Thinking about the similarities in Shahrukh’s and Margarida’s experiences leaves me wondering why it may be easier to acknowledge the needs of immigrant youth without questioning their capacities.

Easier to knit together supports that help them and their families achieve independence.

Easier to recognize the integral roles they play in their families.

Easier than it is to acknowledge that adolescents who grew up in our own communities and systems are also a force for good.

***

Read all The Remix with Karen Pittman’s columns on Youth Today.

Karen Pittman is a partner at KP Catalysts and the founder and former CEO of the Forum for Youth Investment.