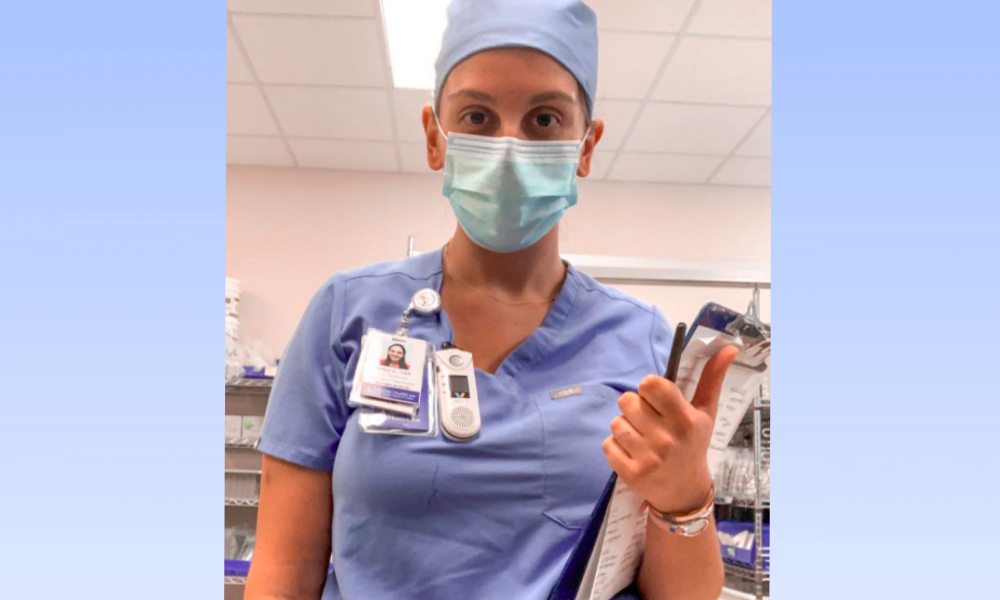

Courtesy Aaryn Zimmerman

Aaryn Zimmerman is an emergency department technician in Maryland.

Before COVID-19, I graduated from the University of Maryland with a bachelor of science degree in the biological sciences. I also received my nursing assistant certification and got a job working as an emergency department technician for the Adventist HealthCare Germantown Emergency Center in Germantown, Maryland.

I was excited to work toward fulfilling the prerequisites for graduate school. My ultimate dream is to work as a physician assistant in emergency medicine.

Never in my life did I expect to be working on the front lines as a recent graduate. None of the volunteer experience I had in college working as a patient care volunteer for Children’s National Hospital or even what I learned in school to become a nursing assistant could have prepared me for what I’ve seen on the front lines.

There is no such thing as a normal day, as one day runs into another. Before I leave the house at 5:45 a.m., I take my vitamins and make sure I have a change of clothes and a scrub cap, which I wear to protect my ears from the straps of both the N95 and surgical masks.

As I get closer to the hospital, I put on my scrub cap and surgical mask. When I get to the parking lot, I close my eyes and take slow, deep breaths to try and calm myself as I face another day. As a stage four cancer survivor with lung scarring following mass quantities of chemotherapy, I am especially vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19.

I grab my work shoes from my trunk, where I keep them so I don’t contaminate the inside of my car or home. I put them on and head into the emergency room. Inside, I put a new N95 on under my surgical mask, my laboratory goggles and face shield. The Emergency Department technician from the night shift gives a report at 6:45 a.m., and I begin my work at 7 a.m.

Wearing the personal protective equipment serves as a reminder to be cautious, but it is so unwieldy and incredibly hot. The first time I put it on, I got claustrophobic, did not breathe properly and almost passed out. I move more slowly when it’s on and have to take a break every couple of hours to take off my masks and get some fresh air.

The personal protective equipment has changed the way I do my job. Medical professionals are facilitators of healing, and we do this in part through human connection, touching, listening and understanding. However, that is a real difficulty now.

Hard to sleep

The way I interact with the patients has changed because I need to minimize my exposure to the virus. When I volunteered at Children’s National Hospital before COVID-19, I was much more hands-on. I would hold the kiddos as we played with toys, give them high-fives and snuggle the babies in the neonatal intensive care unit. When I was doing my clinical rotation at a nursing home when I was getting my nursing assistant certification, I was also more hands-on with the patients.

As a cancer survivor, I fear for my own personal safety and have to be very cautious. Additionally, the patients are often so short of breath I do not want them to carry on a full conversation, so we use nodding to communicate how they’re feeling.

My shift can include inserting IVs, collecting blood specimens, applying orthopedic devices such as splints and slings, irrigating wounds, performing electrocardiograms, irrigating ears, taking vitals signs and doing cardiopulmonary resuscitation when a patient is coding.

Depending on how busy the department is, my shift ends between 7 p.m. and 9 p.m. At the end of my shift, I recycle my N95 and put my laboratory goggles and face shield in the brown paper bag I leave at work. I shower in the locker room and put everything in a plastic bag. When I get to my car, everything gets put in the trunk. When I arrive home, I shower again and wash and dry my clothes immediately.

Even when I’m off shift and home, I worry. At night, I have a hard time sleeping, and when I do sleep I am so restless that I feel more tired when I wake up. The scenes from work replay in my dreams. I see my patients’ eyes looking to me for answers or reassurance, and the constant worries and fears of the other technicians, nurses and doctors.

About a week ago, I felt so overwhelmed. I couldn’t do anything and had no desire to do anything. It was as if I were stuck in quicksand and couldn’t pull myself out of the dark abyss. I had never experienced anything like that before.

On my day off, I went for a bike ride and took some time for myself out in nature, which I find incredibly healing. I journaled and reflected and meditated and that helped me get out of it.

I haven’t given my career choice a second thought during this pandemic. It has been both an honor and privilege serving the community on the front lines with my fellow medical professionals.

Aaryn Zimmerman is an emergency department technician for the Adventist HealthCare Germantown Emergency Center in Germantown, Maryland. She recently graduated from the University of Maryland with a bachelor of science in biology and is working toward becoming a physician assistant specializing in emergency medicine.