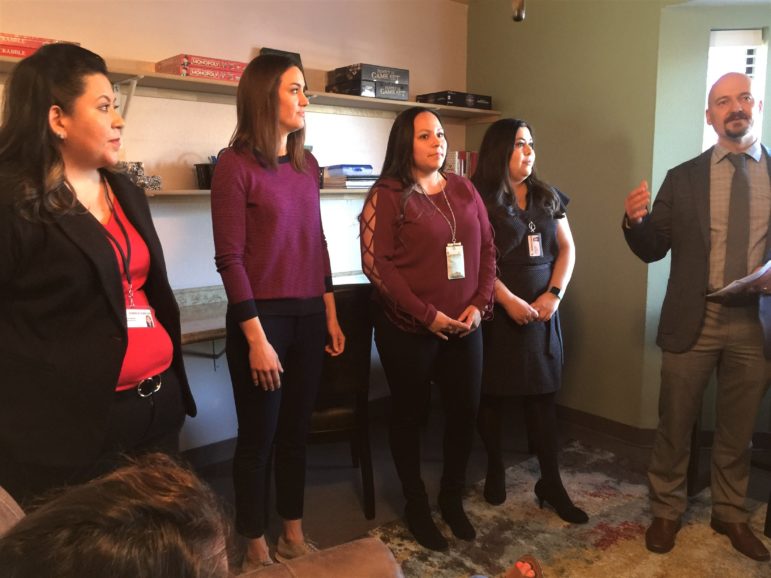

Jacqueline Devine/Sun-News

Brian Kavanaugh, CEO of Families & Youth Inc., stands with My Friend’s Place core team members (from left) Jolene Martinez, Lindsey Davis, Jennica Bustamante and Veronica Doil in a Feb. 28, 2019 file photo.

For a couple of years, homeless foster youth, runaways and other at-risk children in southern New Mexico had a handful of emergency housing choices. They just happened to be hundreds of miles from Las Cruces.

“A lot of youth were being displaced from their community here and having to go to Albuquerque, Taos, Santa Fe or Farmington because that’s where all of the youth shelters are mainly located,” said Jennica Bustamante, shelter supervisor at My Friend’s Place in Las Cruces.

“There was literally nowhere to go prior to our opening,” she said. “There was only treatment foster care and regular foster care.”

My Friend’s Place filled a titanic gap when its 16-bed emergency shelter for homeless, abused and runaway youth aged 12 to 17 opened in February 2019. Once a vulnerable youth turns 18, they may be eligible to live in an apartment run by nonprofit El Crucero (The Crossing), a permanent supportive housing option for aged-out youth in care, low-income persons or people with disabilities.

Though My Friend’s Place and El Crucero are successfully filling a crucial need for at-risk youth and families in the Las Cruces area, the two organizations, which are under the nonprofit Families and Youth, Inc. (FYI) umbrella, face longstanding obstacles as well as challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Filling the Gaps

Crisis housing didn’t exist for Doña Ana County youth for approximately two years. The FYI-run Stepping Stones, a teen group home that was located on the same site as My Friend’s Place, faltered shortly after New Mexico’s behavioral health shake-up in 2013. In February 2018, the Las Cruces City Council unanimously approved $361,000 in start-up money for FYI to help reopen the only teen shelter in southern New Mexico.

The crisis shelter, which has a maximum capacity of 16 (eight girls and eight boys), also links youth to additional community services, such as mental health providers, medication management and help with school enrollment.

“Whether they’re in foster care or in families that are going through hard times, youth can come here for shelter services and we maintain them in their schools,” Bustamante said.

El Crucero, a 12-unit housing complex, is also more than a safe and permanent haven for struggling youth and families, according to program supervisor Terry Armstrong. The program provides case management services, ranging from resume development and employment procurement to parenting support and life skills classes. Additionally, Armstrong, who recently moved to Las Cruces from Albuquerque, instituted the Earn Differently program for residents who are talented artisans.

“Some of the residents, because of mental health challenges, can’t work in a traditional environment. They’ve tried and tried and tried and it just doesn’t work,” said Armstrong, who was formerly employed by Goodwill Industries of New Mexico and Albuquerque Health Care for the Homeless. “There are multiple artists here and they’re good, so we provide a space to make arts and crafts, which they then sell to bring in additional income.”

El Crucero currently houses 25 children and 14 adults, he said. Nearly every resident is an aged-out youth in care. There’s also a waiting list — Armstrong says that approximately 90% of applicants are single mothers with multiple children.

Despite successes by the two FYI programs, it’s not easy to connect vulnerable individuals with behavioral health providers in southern New Mexico. “Mental health services are still hard to come by due to what happened a few years ago,” Armstrong said.

[Related: COVID-19 Adds to Woes of Homeless New Mexican Youth Who Age Out of Foster Care]

[Related: Homeless Youth in Northern New Mexico the Focus of 2-Year Project]

[Related: New Mexico Foster Care Intended to Become ‘Trauma Responsive’ in Lawsuit Settlement]

[Related: COVID-19 Changes in Eddy County Mean Fewer Referrals, More Donations]

Older foster youth face an uphill battle in another way. “Once they turn 18, the services that are available to them are slim to none,” Bustamante said. In 2019, New Mexico extended foster care from age 18 to 21. The Children, Youth and Families Department is about a year into a three-year implementation process.

“It puts youth in difficult spots because they’re unsure how to navigate the system. We do a 30-day follow-up [after a youth turns 18], but the interaction once they leave here is very minimal,” Bustamante added. “I hope that once extended foster care comes into play, our youth who are 17 will get that continuum of care that they need once they turn 18 and continue on into adulthood.”

Coronavirus Responses

In an effort to prevent community transmission of the coronavirus, My Friend’s Place increased its sanitization procedures in March and halted some of its admissions. According to Bustamante, the shelter isn’t accepting youth who aren’t Doña Ana County residents or any Doña Ana County youth who have left the county, then returned until 14 days have elapsed.

“Though we’re not accepting these admissions, we also haven’t received any referrals since we made that decision,” Bustamante said.

As a result of the pandemic, the residents of El Crucero are without laundry service, due to concern about potentially contaminated surfaces and lack of social distancing in the shared space. Though this might not sound crucial, Armstrong calls the laundry facility a “lifeline” to the residents. Additionally, specialized case management services that Armstrong personally provides, such as help with writing a resume, have been put on hold.

As of late March, Armstrong was still delivering breakfast and lunch to every resident. “I go door to door with my gloves and boxes full of food. It’s huge for them right now,” Armstrong said.

This story is part of a Youth Today project on foster care in New Mexico. It’s made possible in part by the May and Stanley Smith Charitable Trust. Youth Today is solely responsible for the content and maintains editorial independence.