Photos by Greenwood Cultural Center

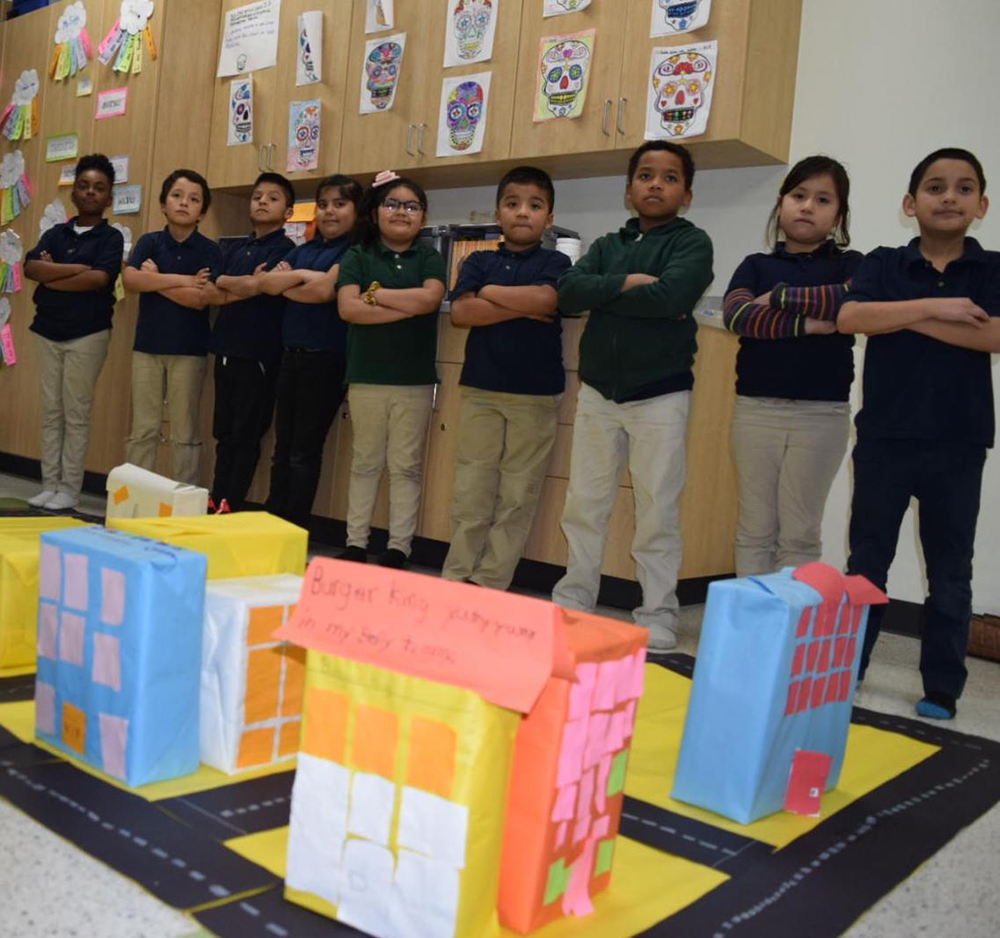

Children in the Greenwood Community Center after-school program in Tulsa, Okla., stand behind the model town they built representing a new version of Black Wall Street, the African-American business district that was destroyed by a white mob in 1921.

TULSA, Okla. — Large black-and-white portraits of people who were young a century ago line the walls of Greenwood Cultural Center next to the Oklahoma State University-Tulsa campus. Underneath each portrait is that person’s recollection of what happened to them in May 1921.

On the day of the riot, I remember running with my parents, siblings and other fleeing blacks.

—Joe Burns, born in 1915

My mother never forgot that day as long as she lived. She said she ran nine miles with me, a nine-day-old baby, in her arms.

—Leroy Leon Hatcher, born in 1921

I saw a truckload of dead bodies being carried somewhere.

—Genevieve Elizabeth Tillman Jackson, born in 1915

Going back to Greenwood was like entering a war zone. Everything was gone!

—Ernestine Gibbs, born in 1902

These survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre, in which as many as 300 people were killed, lived through a white mob shooting, pillaging and burning 35 acres of black-owned homes and businesses.

The violence took place in the Greenwood area of Tulsa known as Black Wall Street, where in the early 1900s African Americans bought land, built prosperous businesses and created one of the most affluent African American communities in the United States.

Nearly 100 years later, the Greenwood Cultural Center, which has exhibits, offices and event space, transmits the history of Black Wall Street and the Tulsa massacre through its programming — including an after-school and summer learning program.

Historical knowledge

“In schools they are not teaching that history yet,” said Mechelle Brown, program coordinator at the Greenwood Cultural Center. Many children born in Oklahoma never learn about it, she said. This year, for the first time, the state is introducing a curriculum for all Oklahoma schoolchildren.

Greenwood altered its longtime summer program three years ago to focus on entrepreneurship as a way to teach about the creation and destruction of Black Wall Street.

“I realized these were children [in the summer program] who were not really connected to this history,” Brown said.

The monthlong Young Entrepreneurs program serves 110 kids ages 5 to 12. Among other things, they learn about the Dreamland movie theater, the hotel built by J.B. Stratford and the work of O.W. Gurley, who originally envisioned the black enterprise district and bought the land. Kids learn about the destruction of the district and how many residents challenged the city in order to rebuild it.

“Up From the Ashes,” a children’s book read in the after-school program, tells the story of the creation, destruction and rebuilding of Tulsa’s Black Wall Street.

In the summer program, kids think up child-sized enterprises they would like to start. To get ideas, they visit local businesses. Kids have made and sold pottery, lip balm or food items, among other projects. The program’s culminating event is a marketplace where they exhibit and sell their products to a group of 200 to 300 parents, grandparents and friends.

“They get to keep the proceeds,” Brown said. They probably earn $20 to $30, which can be a lot to 8-, 9- and 10-year-olds, she said.

The program introduces the idea of business ownership, she said.

“They really never thought of owning their own business before,” she said. Their families may not have a lot of money and their parents or grandparents may never have owned a business.

Greenwood Cultural Center also sponsors an after-school program at McKinley Elementary School for second and third graders. It uses the Children’s Defense Fund Freedom School model. These young children also learn the history of Black Wall Street.

They are asked to think about businesses the community might need, said Kevin Ross, an instructor in the program. Children build a shoebox-and-construction-paper structure to house their businesses, which have included veterinary clinics, shoe stores and hospitals. When all the structures are done, they are assembled into a small-scale town.

“They’re building a brand-new Black Wall Street with the spirit of the old,” Ross said.

Lessons from Black Wall Street

Faith in business might not be the main lesson that some would take away from the 1921 racially motivated massacre in Tulsa. Nevertheless, the Greenwood Cultural Center’s focus on black entrepreneurship carries a message the center would like to impart.

The rebuilding of Black Wall Street — the reconstruction of homes and businesses in the 1920s — is shown as a story of perseverance and indomitable spirit. Entrepreneurship is thus offered to young people as a way they too can persevere and succeed in this world — as their ancestors did.

The youth programs at Greenwood Cultural Center are highly local, focusing on momentous events that occurred footsteps from the front door. Recounting that history locates young people in a place and time and shows their connection to it. The story brings into the open both racial hatred and the transcendence of hatred. It also presents an implicit message about the economic motivations underlying racism.

Starting with one’s own culture

Culturally relevant teaching uses students’ culture as a vehicle for learning, and it can nurture the dreams and aspirations for African American students, wrote Gloria Ladson-Billings, professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Education. She coined the term culturally relevant pedagogy.,

This type of teaching has the potential to strengthen students’ identity while also encouraging critical thinking. Students in Tulsa might ask, for example: Why did a white mob burn down one of the most prosperous African American business districts? Why did some black business owners stay and rebuild while others decided to leave?

Teaching about horrific past events has an important rationale, Ladson-Billings wrote in an introduction to a book about teaching the Holocaust: “How would I ever have known about your suffering without this effort? How can we prevent this from happening again?”

One of the goals of this type of teaching is to transform students from passive recipients of knowledge to active, participatory citizens, according to Ladson-Billings.

Culturally relevant teaching is generally discussed as something that happens in schools, but it doesn’t need to be confined to schools. Greenwood Cultural Center was already a repository of the history of the Greenwood District and already operated a youth program. Local museums, libraries and cultural centers may have similar resources.

Local history is very often not taught to kids, wrote Coshandra Dillard in Teaching Tolerance.

However, it allows kids to connect that history to issues they see around them, such as inequities among people, she said.