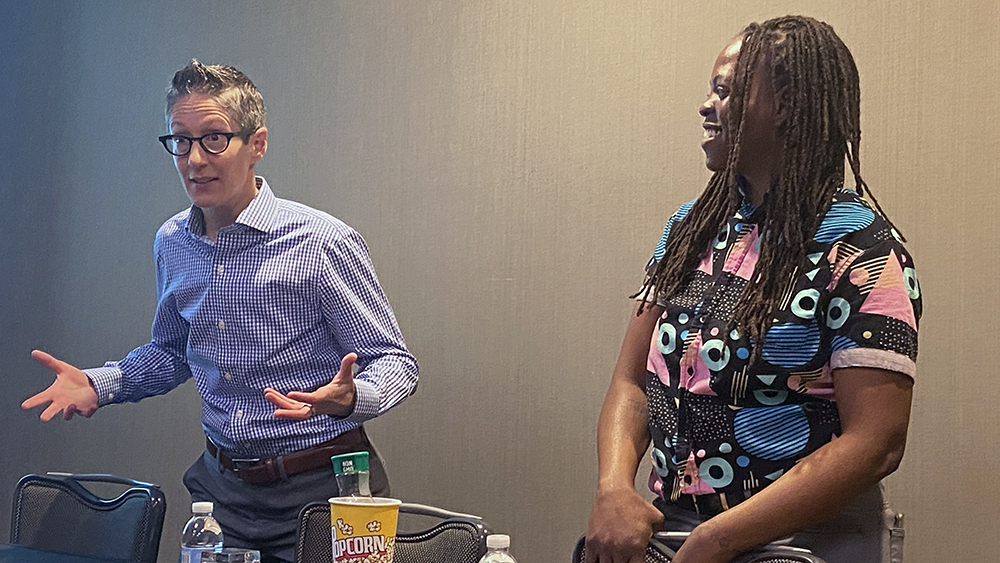

Colby Swettberg (left), CEO of the Silver Lining Institute, and colleague Christina “Mobile” Burrell, its program manager, discussed how paying special attention to mentoring foster youth pays off at the National Mentoring Summit in January. | Allison Stevens

WASHINGTON — Born to a prostitute with a drug problem, April (a pseudonym for her privacy) was removed from her home about two decades ago and sent to live with a relative. But she didn’t get the care she needed there either: She was physically and emotionally abused and sent to live with a foster mother.

At 11, April faced a bleak future: Kids in foster care are less likely to finish high school, graduate from college and hold steady jobs than their peers in the general population, according to FosterClub, a nonprofit organization. Fewer than 3% earn college degrees, about half are unemployed at 24 and more than 70% of young women are pregnant by 21. Youth of color, religious minorities and those who identify as LGBTQ face additional challenges.

But April beat the odds: Now 25, she completed high school, earned a bachelor’s degree at an area college and avoided teen pregnancy.

One resource that helped her achieve her goals: her mentor, Michelle (also a pseudonym).

When April was 11, she and Michelle began spending a few hours together every weekend. They visited parks, saw movies and plays, and sometimes just hung out in Michelle’s apartment. Fourteen years later, the pair still see each other — and Michelle has a shoebox full of ticket stubs, receipts, photos and other memorabilia that tell the story of their deep bond.

“She just became part of the family,” Michelle said.

The stable presence of a caring adult like Michelle in a young person’s life — even for just a few hours a week — can help youth overcome adversity, build resilience and access support services, research shows. Such mentors are especially valuable for youth in foster care, who are uprooted from their homes and communities every time they are assigned a new placement, which can happen multiple times in a single year.

Volunteer mentors are often the only adults in the lives of system-involved youth who are not paid to be there.

Mentoring gives foster youth sense of belonging

Yet few mentoring programs are designed to meet the unique needs of youth in foster care, according to Colby Swettberg, CEO of the Silver Lining Institute in Massachusetts. Few are set up so mentors can follow foster youth as they move from placement to placement and as they transition out of the system at age 18.

Program design can be problematic too, Swettberg said.

Mentoring organizations often focus on high-order needs like self-esteem and actualization but overlook a key midlevel need on Maslow’s famed hierarchy — a sense of belonging. Though key to developing higher-order needs, this need often goes unmet among system-involved youth and unaddressed in “one-size-fits-all” mentoring programs.

Silver Lining Mentoring — the organization that paired April and Michelle and that created the Silver Lining Institute — is working to change that. Founded in 2001 by a man who grew up in foster care, it is one of only a handful of groups across the country that focuses exclusively on mentoring foster youth.

The organization recruits mentors who meet mentees regularly in their communities for a minimum of one year and gives them rigorous training. It also pays mentees to participate in workshops that teach life skills, career readiness and financial literacy, offers leadership opportunities and provides specialized support to youth aging out of the system.

The goal is to build resilience by building mentees’ social connections, strengthening their social and emotional skills, fostering positive identity and self-efficacy and more.

Youth in foster care often feel like they don’t have roots, Swettberg explained during a presentation last month at a national mentoring conference in Washington. “We want them to feel connected and held by a network of people who care about them — not because it’s their job but because they are invested in these young people.”

Paying special attention to this group’s needs pays off. Silver Lining Mentoring’s mentor matches last an average of 55 months, far longer than the national average, and youth participants are far more likely to be employed and go to college than their peers in foster care.

Silver Lining Mentoring is the pre-eminent mentoring program serving foster youth, according to Jean Rhodes, director of the Center for Evidence-Based Mentoring — and Swettberg and their team are now working to spread the model across the country.

This fall, the organization launched an effort to share the program’s “special sauce” with partners around the country. The Silver Lining Mentoring Institute educates interested people about mentoring as a high-impact, low-cost intervention for youth in care — a service it provided at last month’s mentoring conference.

The group also has its eyes on policy and culture change, Swettberg said. Ultimately, it aims to educate lawmakers and policymakers at the state and federal level so they understand the challenges facing youth in foster care — and make better policy decisions relating to housing, health care, employment and other areas of life that affect foster youth. And they hope to bring about broader cultural change through media outreach and public awareness efforts.

“Our hope is to build a movement of allies and advocates who will step up for youth in foster care,” Swettberg said.