Photos by Matt M. McKnight/Crosscut

A chalkboard sign welcomes young people outside Cocoon House in Everett, Wash.

SEATTLE — At the age of 16, A.S. had just made his high school football team when his life was upended. His mother was moving overseas, and he would have to go live with his remarried father and four step-siblings in another part of town.

A.S. (he asked that his initials be used to protect his privacy) says he was still adjusting to the rules in his new home when his father discovered he had been smoking pot. His punishment: He was sent to a shelter for homeless and runaway youth for a couple of weeks. From there, his life spiraled downward.

As the conflict at home festered, A.S. dropped out of school and was intermittently homeless. He was arrested for a string of minor offenses, including truancy, until finally his father refused to pick him up following his release from detention — a situation hundreds of Washington youths face each year. “I’ve kind of been on my own since then,” said A.S., a Seattle native who is now 24.

In some ways, A.S. was fortunate: He got a rare spot in one of the state’s only long-term housing programs for homeless minors, Cocoon House in Everett (about 30 miles north of Seattle), where he lived until turning 18. Although he has since experienced brief periods of homelessness, today he has a job, an apartment and dreams of becoming a personal trainer. “I’m trying to get on my feet,” he said.

Many homeless teens aren’t as lucky. Instead, they find themselves falling through the cracks.

Because they are minors, somebody is supposed to be responsible for homeless teens. Often no one is. In those cases, youths have limited options.

Only a handful of homeless shelters in the state are licensed for unaccompanied youths under 18, and they must receive a parent’s permission for a child to stay beyond three days. Funding restrictions force most shelters to limit stays to a few weeks, leading youth to “hop” from shelter to shelter.

Parents kicking teens out or them running away are top causes of such homelessness, yet the state offers few timely resources to support families in conflict. And when home isn’t safe or parents refuse to allow their children to come back, Child Protective Services rarely steps in.

Some youth end up surviving on their own until they turn 18, when they can sign themselves up for a variety of housing programs that offer more freedom and fewer rules.

Those gaps leave younger homeless teens in a dangerous limbo. Even a few nights on the street, where pimps and drug dealers quickly prey on the young, sets them up to be assaulted, arrested or sex trafficked, studies show.

“Most folks, our defenses won’t even let us imagine what it’s really like to be outside all night long surrounded by predators,” said Jim Theofelis, executive director of A Way Home Washington in Seattle. “Two or three nights on the street, the impact of that trauma, we have a completely different young person.”

Halting that downward trajectory is essential to resolving Washington state’s homelessness crisis. Roughly half of homeless adults in King County first became homeless as children or young adults.

“If you want to end adult homelessness,” Theofelis said, “you are going to have to end youth and young adult homelessness.” His organization has launched an initiative to eliminate youth and young adult homelessness in four Washington counties.

The population of homeless K–12 students in Washington more than doubled in the past decade, hitting nearly 41,000 children in 2016–17 — the sixth highest in the country — according to Building Changes. Three out of five homeless students are children of color.

Nationwide, an estimated 1 in 30 adolescents between the ages of 13 and 17 — or about 700,000 children — experience homelessness in a year, according to a 2017 study by Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Recognizing the shortage of options for homeless minors, King County last fall began targeting homelessness specifically among school-age children, with the goal of intervening before kids and families become chronically homeless. The county’s most recent point-in-time survey shows a drop in youth homelessness. A similar program in Snohomish County, Wash., set to launch late this year, will assign “permanency navigators” to assist minors at risk of homelessness in juvenile justice and other systems.

These county efforts are getting a headstart on the state’s ambitious goal of ensuring that no youth are homeless upon leaving juvenile detention, foster care and inpatient mental health and substance abuse treatment by the end of 2020.

As the state pushes to end youth homelessness, advocates are calling for the new Department of Children, Youth and Families, which took over the state’s child welfare system last July, to take a more active role.

Today, when homeless teens can’t reunite with family, it’s unclear whose job it is to care for them until they become adults, said DeAnn Adams, who oversees residential services for minors at Friends of Youth in Kirkland, Wash., 11 miles northeast of Seattle.

“I don’t think anybody is really sure who should own that role,” she said.

Youth ‘shelter hop’ to dodge time limits

In most shelters, teens run into strict limits on how long they can stay: from 21 to 60 days, depending on the funding source.

Those time limits are not realistic for many, say shelter managers, who sometimes use private dollars to allow kids to stay longer.

“It’s just silliness, in my mind,” said Bridget Cannon, director of youth services for Volunteers of America of Eastern Washington & Northern Idaho. “To think that a youth’s homeless situation is going to be solved in 21 days, 30 days, is just an unrealistic expectation.”

Cannon oversees the Crosswalk shelter in Spokane, near the Idaho border, one of the few overnight teen shelters in Eastern Washington. She acknowledges that growing up in shelters is far from ideal. But for 16- and 17-year-olds who can’t go home and aren’t placed in foster care, “where do they go?” she said.

For many youth, the answer is “shelter hopping” — moving to another shelter, where the clock starts over. With each move, they must change case managers, mental health counselors, schools and other sources of stability.

“We are constantly in the situation of sending kids to the next shelter,” said Rachel Mathison, director of programs for Cocoon House, which offers both short- and long-term housing for minors. “That’s not how a kid should live. And then school — how’s a 15-year-old who’s shelter hopping from King County to Bellingham supposed to stay in school?”

Longer-term options are in short supply. Cocoon House hosts 13 of the roughly 25 transitional living spots in Western Washington for homeless minors who are either not parents themselves or aren’t in foster care. Mathison said she sometimes must leave beds empty because she can’t pay enough to hire and retain sufficient staff to supervise the youths around the clock.

Shelters work to reunite young people with family whenever possible, and the majority eventually go home. But those efforts can take longer than a few weeks, staffers say.

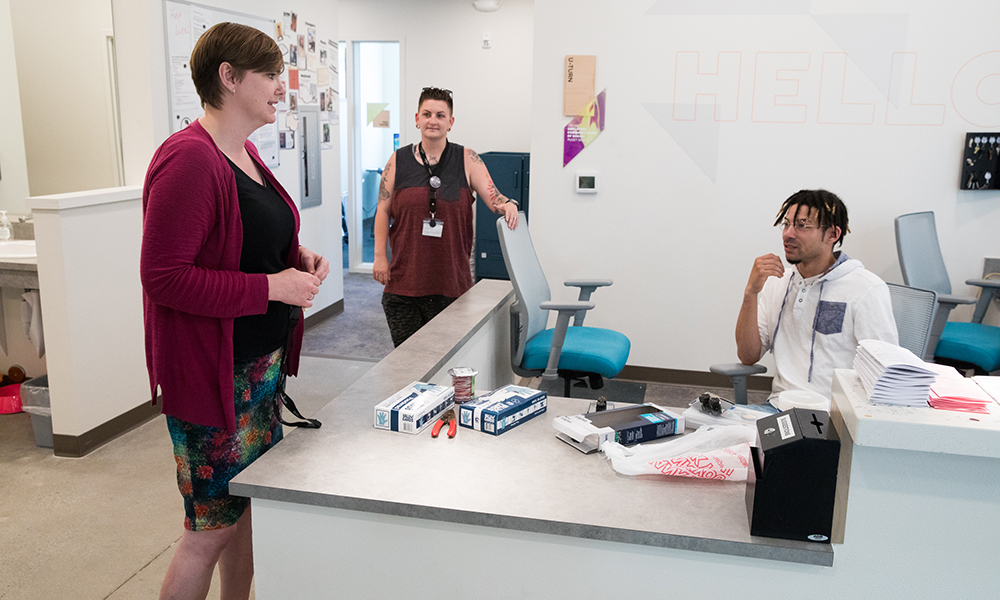

Director of Programs Rachel Mathison speaks with staff members at Cocoon House.

Sometimes parents need extra time to secure a job or an apartment so that a child can return home permanently. And sometimes it’s the youth working to hold the family together.

Mathison recalled a young woman at Cocoon House who each morning brought breakfast out to her mother, who lived in her car. After eight months, the daughter finally landed a job and could afford a place for both of them.

In other cases, the conflicts that drove a teen from the home have been building for years and are not easily resolved, said Friends of Youth’s Adams.

If a youth has reached the point where staying in a shelter “seems more desirable than staying at home, you are often talking about pretty complex, deep-seated challenges,” she said. “Within three weeks, how much complete transformation are you able to effect?”

Legal troubles keep youths on the streets

Homeless youths’ frequent brushes with the law only exacerbate their homelessness. More than 77% of homeless youths in a national study reported having had an interaction with the police, and 62% said they had been arrested. (Washington has been an outlier among states in jailing juveniles for noncriminal offenses, such as running away. A state law passed this year phases out that practice.)

As a result of their frequent arrests, many are dogged by warrants. Youth sometimes stop attending school and avoid shelters because they fear getting picked up, said Erin Lovell, executive director of Legal Counsel for Youth and Children, which represents homeless youths. If they have already been detained for running away, “the next time they run, they just go deeper,” she said.

Criminal records also hinder young people from getting housing. Youth shelters typically bar those convicted of sexual abuse and other violent crimes, and sometimes they turn away youths merely accused of an offense because they fear those youths could pose a risk to others.

Shelters face a tough “balancing act,” Lovell noted. If a shelter isn’t safe, kids won’t come there. At the same time, “putting kids on the street is not a solution,” she said. For youths who are acting out and in need of extra help, “how do we provide [those services] in a way that reaches those young people and also keeps them safe?”

Even after they turn 18, young adults can be haunted by their youthful offenses. Juvenile records are not automatically sealed in all cases, which can thwart future efforts to get housing and employment.

As A.S. found out, spending time in detention also tends to deepen the rifts between parents and their children, increasing the chance youths will be homeless when they are released. The state Office of Homeless Youth is developing a plan to prevent youths from becoming homeless when they exit detention and other publicly funded systems of care, which it will take to the legislature next year.

CPS ‘turns a blind eye’ to homeless youths

For some young people, home will never be safe or welcoming. Where should they live out their childhoods? The child welfare system is supposed to provide the ultimate safety net, advocates say.

Shelter staffers are required by law to call Child Protective Services when youths report abuse or neglect at home, or when parents refuse to pick up their kids. Shelters say they make dozens of such calls each week. Yet the state rarely investigates allegations that involve teenagers, unless young children are also in the home, according to interviews with a dozen shelter workers and attorneys.

“I cannot tell you how many times I or colleagues have called CPS on an adolescent who clearly has been abandoned,” said A Way Home’s Theofelis, who previously ran programs for foster children. “It is almost impossible to get CPS to accept the referral” and for the young person to end up in a safe foster home.

Theofelis and others attribute this inaction to child welfare prioritizing young children, who are deemed more vulnerable. That “has resulted in not only failing adolescents, but actually continues to create adolescents who are homeless,” he said.

Theofelis hopes this will change under the new Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF), which lawmakers created in 2017 with the goal of better serving at-risk children by integrating early childhood education, juvenile justice and child welfare programs. The department is in the process of creating a new unit specifically to address the needs of adolescents.

Fundraising staff work in the offices of Cocoon House.

Asked about the claim that DCYF rarely takes action on calls involving homeless teens, spokesperson Debra Johnson said allegations of abuse or neglect must meet legal definitions in order to be investigated. “It’s really difficult for us to address generalities … without knowing the circumstances of specific youth,” she wrote in an email. Homelessness alone is not a reason for the department to take a child into custody, she said.

If the homelessness stems from family conflict, the department might offer them help through a voluntary program called Family Reconciliation Services, Johnson said in an interview. Those services, however, were cut drastically after the Great Recession and remain very limited.

DCYF declined requests to make an executive available to discuss the department’s role in addressing youth homelessness.

“The reality that a state’s child welfare system can turn a blind eye to youth homelessness and refuse to reach out to these youth is unconscionable,” said Dee Wilson, a 26-year veteran of Washington’s child welfare department. He blames the situation on a definition of neglect that focuses more on parents’ “failure” than on children’s needs.

Plus, DCYF simply lacks the resources to have robust services for adolescents, Wilson added. “If they intervene in homelessness, what are they going to do with the kids?” he asked. “They ought to be lobbying [the Legislature] for some resources” to help homeless teens they can’t place in foster care, such as via family reconciliation or transitional living programs.

Some homeless youths could benefit from the long-term assistance available to foster kids, experts say. In Washington and most other states, children who enter foster care may stay until age 21 and receive help with housing, health insurance and education. One possible solution, said Samantha Batko, a research associate with the Urban Institute, is making homeless young adults eligible for the same benefits.

Others worry that homeless kids won’t fare any better in foster care. With a shortage of foster homes in most states, especially for adolescents, teens are likely to bounce from home to home, be held in hotels or shipped to out-of-state group homes. That instability just contributes to them running away and becoming homeless. Among Washington youths who “age out” of foster care without finding a permanent family, nearly 28% experience homelessness within a year, according to a 2015 study.

Homeless minors shouldn’t be forced into foster care, attorney Lovell said. “That would be a horrible idea.” Many don’t want to live with strangers, and they will “vote with their feet” if they are forced, she said.

But even those amenable to foster care rarely get placed without the help of a lawyer, Lovell said. Her organization sometimes petitions courts to place homeless youths in foster care if CPS won’t initiate a case. “It’s a really sad state of affairs” that children need a lawyer to get help, she said.

Whether or not foster care is the right place for homeless teens, the state must take children’s cries for help seriously, Lovell said. CPS should investigate whenever youths call on their own to report neglect or abuse, she said.

“If they call and ask for help, you have to be prepared to help them,” she said. “Otherwise you might lose them, and you may lose them for decades.”

This article is part of a series by Youth Today on homelessness and its intersection with youth justice. It is made possible in part by support from the Park, Raikes and Tow foundations. Youth Today maintains editorial control.

This story has been updated.