Photos by Forum for Youth Investment

Karen Pittman, president and CEO of the Forum for Youth Investment, speaks at the 2018 Ready by 21 National Meeting in West Palm Beach, Fla.

Karen Pittman is the co-founder, president and CEO of the Forum for Youth Investment, a nonprofit whose goal is to change the odds that young people will be ready for college, work and life.

She recently took part in the Aspen Institute National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development, where she led the Youth Development Work Group. The commission began its work in November 2016 and released a final report in January.

Here, Pittman talks with Youth Today reporter Stell Simonton.

Stell Simonton: The commission produced a report “From a Nation at Risk to a Nation at Hope.” What’s the significance of that report?

Karen Pittman: It’s the first time a broad-based group has been brought together to really articulate both a vision and a set of strategies and recommendations for K-12 education leaders to integrate social and emotional learning into academic development.

This builds off a significant amount of research. That research — both brain research and research on how learning happens — suggests strongly that all of us are social animals. If young people aren’t engaged socially and emotionally, if they don’t feel socially accepted and emotionally safe, then learning anything is impaired.

So [the commission’s work] has been a big push to acknowledge the importance of:

- creating environments in which young people feel safe and supported

- having explicit instruction that names and gives young people a chance to learn and practice social and emotional skills

- making sure that the idea of leading with social and emotional learning is embedded in all courses.

So that’s a three-part menu for school leaders.

SS: You’ve said that right now is a pivotal moment for the youth development field to connect with the K-12 sector. Is that because of the research that has been done or are there other reasons?

KP: It’s both the research that has been done and … the work the commission has done over the past two years to generate a set of consensus documents. That’s the formal report [and] an array of documents developed with commissioners and probably 100-plus people. They include a council of distinguished scientists, a council of distinguished educators, a youth advisory group, a parent advisory group and two ad hoc groups created by popular demand.

One, the Youth Development Work Group, worked to make sure that youth development organizations had an opportunity to review the reports and recommendations. We then pushed for that group to convene and create its own issue brief, “Building Partnerships.”

Learning happens everywhere

SS: Part of your role, as I understand it, was bringing in additional people from the youth development field. You’ve said that it is important to widen our understanding of the settings where young people learn. Can you tell me why that’s important?

Karen Pittman believes the time is ripe for K-12 educators and the youth development field to work together.

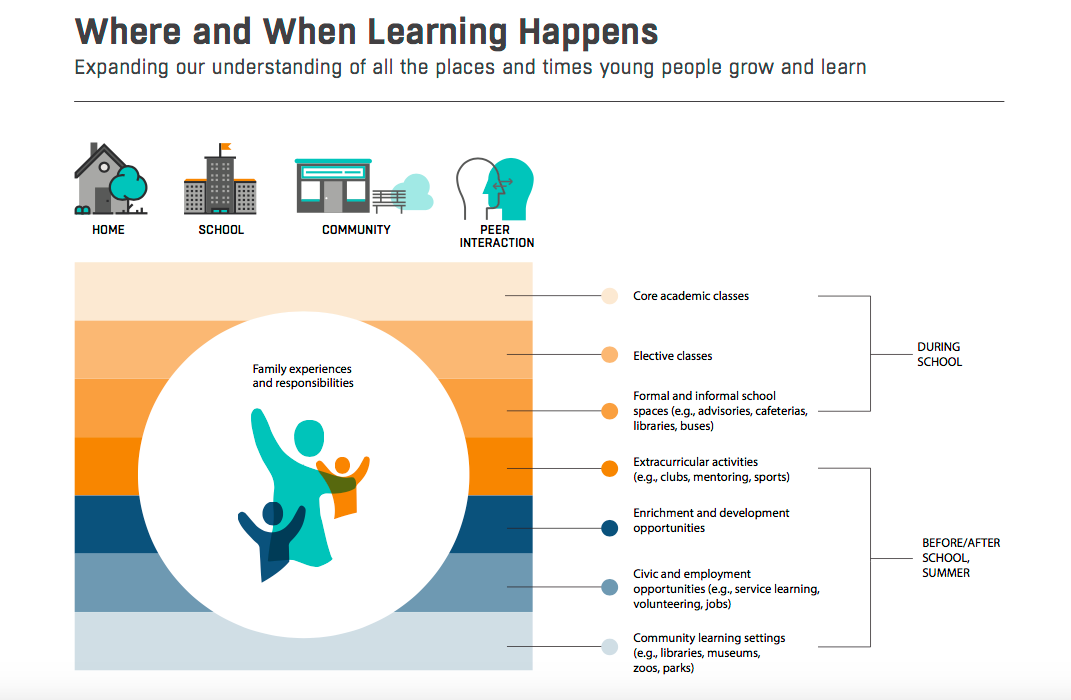

KP: I was probably the only commissioner who came out of the youth development field. It was really important that we ask the commission to broaden its scope to acknowledge the role of what ended up being called the K-12 ecosystem …

I co-chaired a committee with retired Gen. Craig McKinley on outreach and partnership. … It was in that context that I began to explicitly reach out — with some of the Forum’s team — and invite in youth development organizations. And explain why it was important for them to be involved in something that pretty much on the outside looked like it was going to be a set of recommendations for K-12 leaders … It really became critically important … that we work throughout the whole commission to broaden the language and increase the recognition that learning happens in places in school and in places outside of school. And that if we’re really going to address equity issues and embrace this idea that learning is social-emotional we really have to acknowledge the importance that community partners play …

SS: Why is it so important to involve the wider community — not just the schools — in order to provide a greater equality of opportunity for young people?

KP: It’s important for two reasons. One, it’s important purely from a time reason. We’ve known for decades that young people don’t spend most of their waking hours in school, when you count evenings and weekends and summers … Social and emotional skills and competencies [as well as] cognitive skills and competencies are built up in all kinds of learning settings.

We need to do a better job of officially acknowledging where and when learning happens so that we can actually have data to understand where learning isn’t happening, where access isn’t available.

“From a Nation at Risk to a Nation at Hope"

.

The second reason is that every learning environment isn’t equal. We tend to think of schools as classrooms with kids sitting in chairs in rows with a teacher in front of them and we tend to think of out-of-school community as very informal spaces.

[But] an arts program could be in the school building in the school day or it could be out in the community. Pretty much identical things could be happening under the auspices of two organizations, one seen as formal and academic, the other seen as informal and community-based …

We also thought it was very important for educators to realize that there’s a range of learning settings inside the building that schools are responsible for, from the cafeteria to the playground to the library to the counselor’s office to the extracurricular course that you’re taking or the elective course in art to your core academic subjects.

Those present very different opportunities for learning because they have different levels of accountability associated with them, different levels of mandated content associated with them, different levels of staff. When we can get people thinking in a more nuanced way of the range of settings and the range of adults, then we have better opportunities for partnering.

SS: One thing that was not mentioned — as far as settings in which young people learn — is the media. is there a reason the media wasn’t included?

KP: The reason it wasn’t included was purely a matter of time. The graphic [above] went through several iterations. One iteration actually added in the more informal spaces like playgrounds, etc. … Another added the idea that young people, especially high school students, learn in work settings. [The inclusion of] peer interaction was sort of the first push toward recognizing that the people who are involved in learning are not just adults but also peers. … We consider this graphic … a conversation that needs to keep happening and we expect that it will continue to evolve.

What’s wrong with ‘after-school’?

SS: I also want to ask you about the use of language. You’ve had some concerns about the impact of terms such as “after-school” and “out-of-school time.” Can you explain that?

KP: The K-12 system is beginning to think more about expanding — we’re having conversations about expanded learning and extended learning and year-round learning — and now we also have a push for them to expand the competencies that they are responsible for. Not just academic skills and competencies but social and emotional and cognitive competencies.

As the mandate or potential for schools … begins to broaden [in time, content and approach] we need to have a better way to articulate the historic value we have played.

Reducing the richness of what youth development organizations do down to a definition of basically who we’re not — we’re not schools — that definition isn’t descriptive of what we do. It’s just descriptive of how we connect or don’t connect to schools …

[With schools] encroaching on what was typically considered youth development territory, we ‘re not very articulate about why school shouldn’t just take over. … What’s our argument? Is it that we know how to do it better? We train our staff differently? We have different relationships with families? With communities? That we are more flexible? We have to be prepared to explain our value independent of just saying we start where school stops. …

SS: What would you like to add?

KP: This is an important report to bring into conversations about equity. … If we don’t create the right kind of learning environments, we will continue to have learning gaps. If we’re going to fill opportunity gaps we have to fill them not just in school but beyond …

One of the things we also have to be prepared to do … is not to show up at the door of a school and say: “We can bring a program in to serve some of your kids.” We’re going to have to figure out how …collectively the array of youth organizations in a community can work together. … We’re going to have to operate differently than as a set of independent organizations that serve the kids that come to us but that don’t necessarily take responsibility for making sure that all kids are served.

SS: And you feel like this is a hopeful moment for that to happen?

KP: I would say for readers who are old enough to remember it, this report is as important as the National Research Council’s report in 2002. That report gave us common language to talk about what community programs do. We really need to go back to that language and to go back to talking about the value of what we do and the research behind it. …

That report was written to validate what community programs do but this report is saying essentially that we assume community programs are important — we don’t quite understand them — but we need them to be partners with schools.