Photos by Clarissa Sosin

Donna Carter-Heyward mourns her husband Nicholas Heyward Sr. after his death on New Year’s Eve.

NEW YORK — More than a week since Christmas, Donna Carter-Heyward’s Brooklyn apartment still had the cozy warm atmosphere of the holidays. A small Charlie Brown-sized white plastic Christmas tree decorated with tinsel and candy canes sat on a table. A Mickey Mouse race car set and other unopened children’s toys sat underneath it as they had since Christmas morning. The air smelled of eucalyptus and gospel music played from a CD player in the corner.

But there was no joy on Carter-Heyward’s wan face. She looked tired. She kept burying her face in her hands. When she spoke to her “Auntie” Blanche Mance, seated across the table from her, her voice came out raw and cracked. She felt overwhelmed. Either she was fielding phone calls, responding to text messages or answering the buzzer to the apartment.

In the midst of it all, another phone on the table in front of her — not her own — rang. She answered it introducing herself as Donna, Nicholas’ wife, then listened to the person on the other end of the line speak. After a few moments, she explained that Nicholas had died. There was a brief exchange, she said thank you and hung up.

“Donna, you don’t have a voice,” Mance said.

“It keeps going in and out. It be fine one minute and then it just,” Carter-Heyward said, gesturing helplessly with her hands. “I guess from crying so much. It just …” she said, her voice fading away.

“What’s your regret, Donna?” Mance asked her.

Carter-Heyward replied, her voice hoarse, eyes brimming with tears, “That we didn’t have time to spend together,”

Scroll down for video

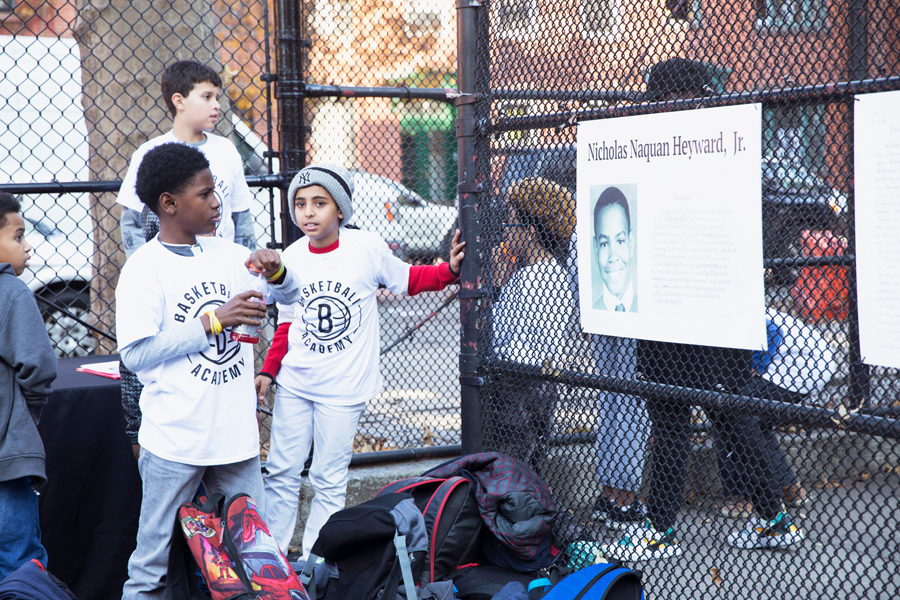

For the three years of their marriage, Carter-Heyward grew accustomed to sharing her husband with the cause that came to dominate his life since a fateful shooting more than two decades ago. On Sept. 27, 1994, his son, Nicholas Naquan Heyward Jr., was playing cops and robbers with a toy gun in the Gowanus Houses projects with friends when he was shot and killed by an NYPD housing officer. He was 13 years old.

Heyward Sr. died of cardiac arrest at the age of 61 on New Year’s Eve after 24 years of campaigning for justice for his son and other people killed by police violence. He leaves behind a wife, a son, an adopted 1-year old son, several grandchildren and many mourning civil rights activists who looked to him as their elder statesman.

After his son’s death, Heyward Sr. became an unrelenting critic of both the NYPD and the Brooklyn district attorney’s office. Brian George, the 23-year-old officer who killed his son, remained on the force, and then-District Attorney Charles Hynes declined to prosecute him. Instead of laying the blame on the policy of aggressive policing championed during the Gov. Rudy Giuliani era, or on the officer patrolling the stairwell with his gun drawn, Hynes pointed to Heyward Jr.’s toy gun — a small version of a cowboy’s rifle with an orange tip and strings connected to the plastic barrel — as the chief cause of the boy’s death. In the wake of the shooting, Hynes advocated successfully to have toy guns removed from New York City’s toy store shelves. George recently retired from the NYPD.

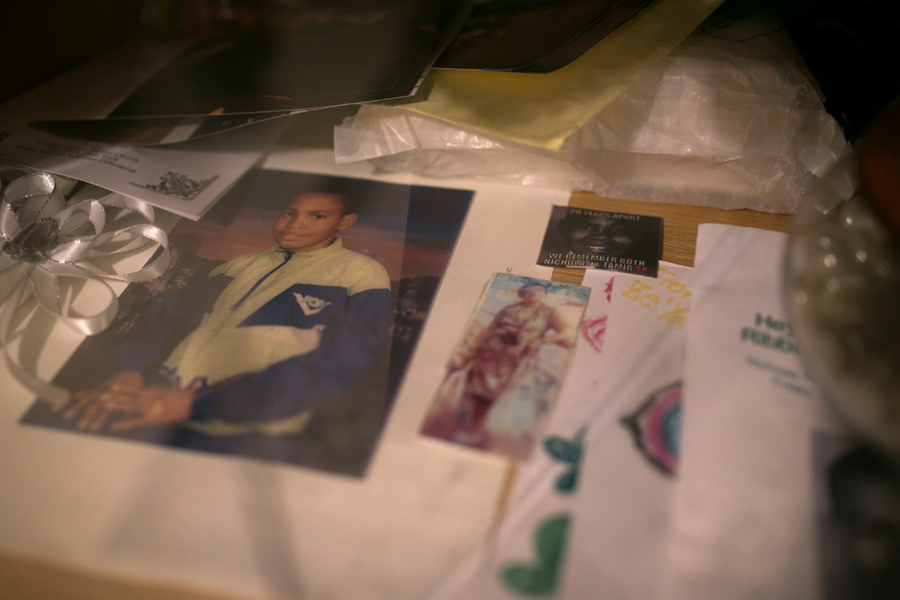

Photos of Nicholas Naquan Heyward Jr. and fliers from the many activism events that Heyward Sr. attended calling for justice in his son’s death and reform in the police department.

It tormented Heyward that no matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t get justice for his son, Carter-Heyward said. And then another person would get killed by a police officer.

“As soon as he heard about another child being killed by the police, he just break down and cry. Because it hits him again. Over and over and over again,” she said. “He keep getting hit with the same thing. Kids getting killed by police for no reason. It just kept pushing him back to the same day when his son got killed by the police. And he was never able to let that go, he was never able to let it go.”

She then turned to the small spiral notebook with the family’s finances in it and went back to figuring out how to pay for burying her husband.

‘He couldn’t forgive himself’

The campaign that consumed Heyward Sr.’s life began with an errand. The day his son died, Heyward Sr. was leaving to go pick up his niece from school in the Bronx. His son wanted to come along with him. But he told him no, to go play with his friends.

Mance said that one exchange haunted him. She said she felt that if he hadn’t seen his son that day when he was leaving for his errand, if he hadn’t told him to go play with his friends, he would have reacted differently.

“It would’ve been a totally different thing,” she said. “I wouldn’t say he wouldn’t go to fight against police brutality, but I would say the guilt wouldn’t be there, and you see the guilt drove him, he couldn’t forgive himself.

“That was one of the reasons Nick was driven so because he felt guilty; he felt responsible,” Mance said. “He never forgave himself for that, he never could. And that’s what drove him and why he pushed himself so hard. Trying to get justice not just for Naquan but for others. Every time he would hear about a killing he was gone.”

Nicholas Heyward Sr. poses for a portrait in the playground at the Gowanus Houses named after his son. He died on Dec. 31, 2018.

Carter-Heyward said he had trouble sleeping. He had trouble keeping still. She remembered waking up at night to find her husband watching the video of Heyward Jr.’s funeral. She would watch him pace the apartment crying. She tried to counsel him to stop.

“You have to stop looking at it,” she would tell him. “It’s not making it better, it’s making it worse.”

But he wouldn’t listen.

“He’d stay looking at that video over and over again and crying. I kept telling him you have to bring yourself up out of that because you’re hurting yourself. You can’t keep beating yourself up over something you had no control over,” Carter-Heyward said. “It was a constant thing with him, constant.”

Mance agreed, saying Heyward was obsessed with that day.

“He re-lived it every day,” she said.

When Heyward Sr. was hospitalized in early December for a heart attack, he was unconscious, but Mance spoke to him anyway, hoping he could hear her.

“Nick, you need to forgive yourself,” she remembers telling him. “It’s not your fault that Naquan got killed. It wasn’t. But you’ve blamed yourself all these years. You need to let it go. Just let it go. No one else is blaming you. You’re carrying this burden all by yourself.”

But she said he didn’t know how.

Photo Gallery

‘He’s got a broken heart’

In 2013, then-candidate for Brooklyn District Attorney Ken Thompson went to the Annual Nicholas Heyward Jr.’s Day of Remembrance, a community event held at the playground named after Heyward Jr. that commemorated his killing. Thompson promised Heyward Sr. that he would reopen the case if he became Brooklyn’s top prosecutor. After Thompson won in 2014, Heyward Sr. continued to pressure him to follow through on his promise and he did.

People familiar with the investigation said that Thompson, who worked on the Emmett Till case when it was reopened in the early 2000s, did not need any pressure. He was committed to his promise to reopen Heyward’s investigation even as he contended with terminal cancer. He was worried that he wouldn’t live long enough to hand over the findings himself. And he didn’t. Later that year, Thompson died suddenly of cancer. The interim district attorney, Eric Gonzalez, promised to follow through on Thompson’s obligation. The case came to a close shortly after with the same findings as in 1994 — the officer was not responsible for Heyward Jr.’s death.

Family and activists who were close to Heyward Sr. said they felt that Gonzalez came to this conclusion because he’d been a chief lieutenant of Hynes when the case was originally investigated by that office.

Bride and groom figurines sit on a bureau with other mementos from the Heywards’ wedding three years ago.

Carter-Heyward remembers the day that she and her husband went to the Brooklyn district attorney’s office. They were only invited after Heyward Sr. had repeatedly called to find out what happened, she said. On the table sat a stack of folders and papers related to the new investigation that the office refused to let them see, she said. He never recovered from that day, she said.

He stopped sleeping. Eventually he stopped eating, she said. His health started to deteriorate. He went to multiple doctors but they couldn’t find anything wrong with him.

“All of the doctors that he was going to see — all of them said the same thing: that he is letting himself go to waste because he’s got a broken heart,” she said.

He even went to a psychiatrist but it was to no avail, she said. After 24 years of fighting for justice for his son and 24 years of consoling other parents whose children were slain by the police, he couldn’t take it anymore.

“Nick, he gave up; he just gave up. He really gave up,” Carter-Heyward said. “He gave up the last time they closed his son’s case.”

A voice to be reckoned with

The news of Heyward Sr.’s death was nearly as much of a blow to his extended family in the activist community as it was to his family. In recent months they had seen his health decline. At his last public appearance campaigning for justice on behalf of his son, he appeared weak. He relied on a walker to make his way across the basketball courts in the playground dedicated to his son’s memory.

When he spoke to the crowd, Anthony Beckford, a cop watcher, community activist and close family friend, had to hold the megaphone up for him. The speech was uncharacteristically short. He thanked the crowd for coming and commented on the lack of support from the houses where his son died. He then apologized to the sparse crowd, explaining that he didn’t feel well enough to continue.

Beckford said Heyward’s passion and dedication inspired a generation of people in the civil rights movement dedicated to ending police brutality.

“He was a voice to be reckoned with,” Beckford said. “He made a lot of people speak out who would have remained silent when it comes to the fight for justice. He’s the reason so many people joined the fight against police violence. He supported every family out there.”

Nicholas Heyward Sr. speaks with activist and community organizer Josmar Trujillo at the 2018 Day of Remembrance for his son. This was his last public event.

Josmar Trujillo, a writer and community activist, credits Heyward Sr. for laying the foundation for the Black Lives Matter movement and modern activism against police brutality and killings. Today, he said, critiques of police have become a central part of the mainstream political discourse. But when Heyward Sr. started, he was up against a city that was embracing aggressive police tactics and a country that had passed what is now considered a draconian criminal justice act.

“He’d seen the worst of it. He had already gone through it at a time when it was even more marginal,” Trujillo said. “The power brokers, they didn’t know what to do with someone like Nick.”

Many young activists looked to Heyward Sr. as a father figure and an elder statesman in the movement, Trujillo said. His perseverance and uncompromising fight inspired them.

“When people heard that story and they made that connection, it gave a standing to the movement,” Trujillo said. “It wasn’t a fly-by-night political fad of the moment.”

Despite his commitment on the frontlines of the movement, Heyward Sr. remained a dedicated father. As a father himself, it was something that impressed Trujillo. If such a tragedy were to ever happen to him. he doesn’t think he’d be able to summon the grit to carry on as Heyward Sr. had.

“What he always wanted people to acknowledge was not him and his work. He wanted people to acknowledge his son,” he said. “He was so in love with his son.”

Calling for justice from his grave

Nicholas Heyward Sr. and Donna Carter-Heyward adopted Adonis together before Heyward Sr.’s death. Adonis is 1 year old here.

Before Heyward Sr. died, he and Carter-Heyward adopted an infant boy, Adonis, now almost 2. With chubby cheeks and an ever-smiling face, Adonis accompanied his parents to marches and rallies wearing his own toddler-sized red “Team Nicholas” T-shirt.

Heyward Sr. first went to the hospital in the beginning of December. Adonis, too young to understand what was happening, has been asking for him ever since.

“It was always Dada, Dada, Dada,” Carter-Heyward said. “He worshipped the ground that he walked on.”

To placate him, his mother scattered pictures of his father around the apartment and occasionally even gave him one to hug.

“I play all along with him because I don’t want him to forget him,” Carter-Heyward said. “I need to let him know that his dada did exist.”

A tote bag with photos of Donna Carter-Heyward and Nicholas Heyward Sr. hangs on a hook in the apartment.

Even when he was alive, it was a struggle to keep Heyward Sr. focused on his domestic life. There was always someone calling him to join in the latest fight. She knew that he was considered a warrior for the movement but she felt that it took its toll.

“‘We need you on the frontlines!’ That’s all he kept hearing,” Carter-Heyward said. “I had to tell him, ‘Listen, it’s all right for you to be on the frontline. But, you have a wife, you have a child, you have grandkids, you have a little baby that we just adopted, and you have a whole host of family that need you on their frontline.’”

Mance was at Heyward Sr.’s side in the days after his son’s death. Over the years she watched his grief consume him, she said. There was no balance in his life. He was always dealing with the most recent tragedy.

“His focus was like tunnel vision,” said Mance, motioning with her hands. “It’s not that he didn’t love Donna, he did; it wasn’t that he didn’t love his family. But he had a purpose and the purpose overtook him.”

Among the hurly-burly of calls and visits, state Assemblyman Charles Barron arrived to help organize the funeral. All the chairs were taken so he asked if it was OK to sit on a bench.

Heyward Sr. had wanted to be buried next to his son in Pinelawn Cemetery in Farmingdale, N.Y., on Long Island, but he had made only a small down payment on the plot. The city paid for his son’s burial, but the family was responsible for his and $8,490 was too steep a price tag. They had started a GoFundMe page to help defray costs but wouldn’t have all the donations in time. They talked about possibly saving money by finding a singer or musician in the community instead of using the staff attached to the funeral home. Barron called a pastor at a nearby church to see if he could help out.

Barron, formally a firebrand city councilman, had attended a number of press conferences over the years to advocate for Heyward Jr.’s case and to call for reforms and transparency in the NYPD, most recently during Thompson’s reopening of the investigation.

“He had a passion, he had a drive, a drive for justice that wouldn’t quit,” Barron said. “The only consolation in all of this is that he can be at peace with Nicholas, his son; they can finally get together. He can tell him, ‘Dad, I’m really proud of you. Thanks for the fight.”

Barron said the fight for justice for Heyward Jr. would continue. But he worried aloud that if the city and the country isn’t willing to change its ways by the type of fiery but peaceful persuasion that Heyward Sr. dedicated the last two dozen years of his life to, then people will resort to other means. At the beginning of the Black Lives Matter movement, he would attend rallies where people would chant: Hands up, don’t shoot! Now the rhetoric is taking a darker turn, he said.

“They’re saying: ‘Hands down, shoot back!’” he said. “You got to hear us. You got to hear Nicholas from his grave. Calling for justice from his grave for his son. You got to hear him, or else there’s going to be an explosion.”

Barron was the only politician to pay a visit to the home. Carter-Heyward said she hadn’t heard from anyone from the city — not the mayor’s office, not the district attorney’s office, not the NYPD. She feels the city owes her family the respect of at least a call but that maybe it’s for the best that no one bothered to reach out.

She doesn’t think they would want to hear what she has to say.