Kathy Deal

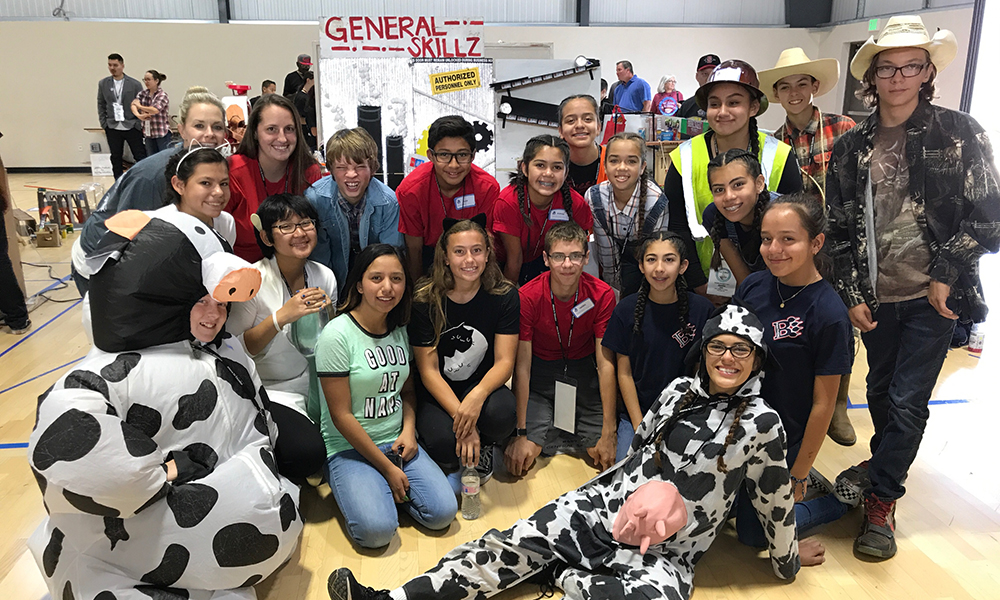

Eighth graders from Lyle S. Briggs Fundamental School in Chino, Calif., each had a function important to their winning entry’s story, including students who dressed up as cows.

When the cereal box slid down and dumped its contents in the toilet, the eighth graders cheered. They had successfully built a 42-step “Rube Goldberg” apparatus that won first place in the 30th annual Rube Goldberg Machine Contest (Division I) in April in Chicago.

It took teamwork and humor, said students Haden Garcia and Katrina Hitchcock from Lyle S. Briggs Fundamental, a K-8 Title I school in Chino, California.

Their experience provides tips for youth workers and teachers interested in this STEM project that develops skills while invigorating kids with its absurdist humor.

Who was Rube Goldberg?

Rube Goldberg machines are contraptions that perform a simple task in an absurdly complicated manner. They’re based on the cartoons of the real Rube Goldberg, who was wildly popular in the early 1900s and whose name became synonymous with the machines he drew. One of his mousetrap cartoons, for example, lures a mouse with a picture of cheese, causing the mouse to step on a hot stove, jump to an escalator, fall on a boxing glove and get knocked into a rocket that sends him to the moon.

For 30 years, the Rube Goldberg Machine Contest has lured kids to create multistep gizmos to do things like adhere a stamp to a letter (1988), shut off an alarm clock (1998) or assemble a hamburger (2008). This year’s challenge was to pour a bowl of cereal.

Goldberg’s granddaughter, Jennifer George, was tickled by the Chino kids’ winning entry.

“They built a machine that told the story of their town,” she said. George is the legacy director of Rube Goldberg Inc., which runs the contest.

Telling a story

Chino is a dairy farming area; the machine showed how milk gets from farm to table. A marble rolls through a toy farm, triggers a cow to chomp, sends other marbles through the cow’s winding digestive system, pushes Wiffle balls through a “milk processing factory,” knocks a milk jug onto a conveyor belt, triggers an “open” sign at the store and lifts a cereal box on a giant spoon to pour Cheerios into a large mouth in a toilet bowl.

The appeal is “a combination of the invention, the kids, the narration they improvise and the humor,” George said.

Rube Goldberg projects engage all types of students, she said. The “scientists” in the group make sure the machine works, the artists make the contraption look good and the storytellers make up the story told by the machine. The kid who clowns makes sure the machine is funny, and the actor stands up and introduces the machine, she said.

Danielle Weinstein, the Lyle S. Briggs science teacher who was the team coach, said the project teaches creativity, collaboration, critical thinking and communication.

“A lot of learning happens intrinsically,” she said.

Danielle Weinstein

Get ready for failure

Repeated failure is the biggest part of the learning experience, Weinstein said.

“You’re going to fail a lot,” she said. “You need perseverance.” Patience is necessary to perfect the machine.

Students particularly struggled with getting the conveyor belt to work, said Garcia, the student.

Weinstein created an after-school club at the school to take on the project. The group began on Sept. 11 last year, meeting one afternoon a week at first, then two afternoons per week and then working until 10 p.m. the night before the Nov. 4 regional competition.

Initially, 22 students were involved, but only 10 could be on the official team. Through a process of reflection, writing and voting, the students determined which 10 would be official members.

Students spent about 1,000 after-school hours working on the project, Weinstein said.

“A good project takes a lot of time,” she said.

Research is important. Weinstein and the students watched numerous YouTube videos of previous contest entries and gathered ideas.

Butting heads

The hardest part was working together as a team, Garcia said. The group had some strong personalities who were insistent on doing things their way, he said.

“Not everybody gets along,” he said.

Weinstein had them do team-building exercises, such as going to an escape room.

“We had a come-to-Jesus meeting,” said Hitchcock, the student. Tensions were lessened when the group designated individual team members as experts in various areas, such as woodworking and narrating the project.

While Rube Goldberg machines are constructed from everyday objects, the Chino group still needed to buy some materials.

Since more than half the Chino students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunches, they had to raise money and approach businesses such as Home Depot for discounts in order to buy materials costing nearly $3,000.

After winning the regional competition, they raised about $31,000 to go the finals in Chicago, Weinstein said. Students created a fund-raising letter, among other things. Packing and transporting the machine was a challenge, Weinstein said.

Danielle Weinstein

The contraption built by eighth graders from Lyle S. Briggs Fundamental School in Chino, Calif., uses a series of simple machines to pour a bowl of cereal. It also tells a story about their dairy farming area — how milk gets from farm to table to toilet.

The value of “making”

Building Rube Goldberg machines is a “making” activity, and research into “making” and “tinkering” shows they have great educational value, according to researchers Bronwyn Bevan, Jean Ryoo and Molly Shea.

After-school is an ideal place for this kind of activity, they wrote in an article in a spring 2017 article in Afterschool Matters.

In addition, after-school programs “can play a vital role in leveling the playing field” for students in under-resourced schools by giving them the chance to learn STEM by doing it, they wrote.

Active, collaborative learner-driven projects are key ingredients in youth development, they said.

Instead of memorization, students are involved in the process of inquiry.

Bevan, Roo and Shea said the process of “making”:

- Develops problem-solving abilities as students create and improvise,

- Builds persistence, self-efficacy and agency, and

- Deepens students’ understanding as they repeatedly design, test, redesign and refine.

The best way to learn STEM skills, they said, is to engage in the following practices detailed by the National Research Council:

- Investigation, which involves questioning, planning, undertaking the investigation and using mathematical and computational thinking,

- Sense-making, which involves creating models, analyzing data and developing explanations, and

- Critiquing, which involves getting, assessing and communicating information and taking part in argument using evidence.

“Making” activities encourage risk-taking, expand students’ vision of their future, and enable collaborative learning, according to Bevan, Ryoo and Shea.

Jennifer George sees an additional benefit: fun for adults as well as kids.

“The teachers have such an awesome time,” she said. And they have the opportunity to engage every student, she said.