Trudy Powell

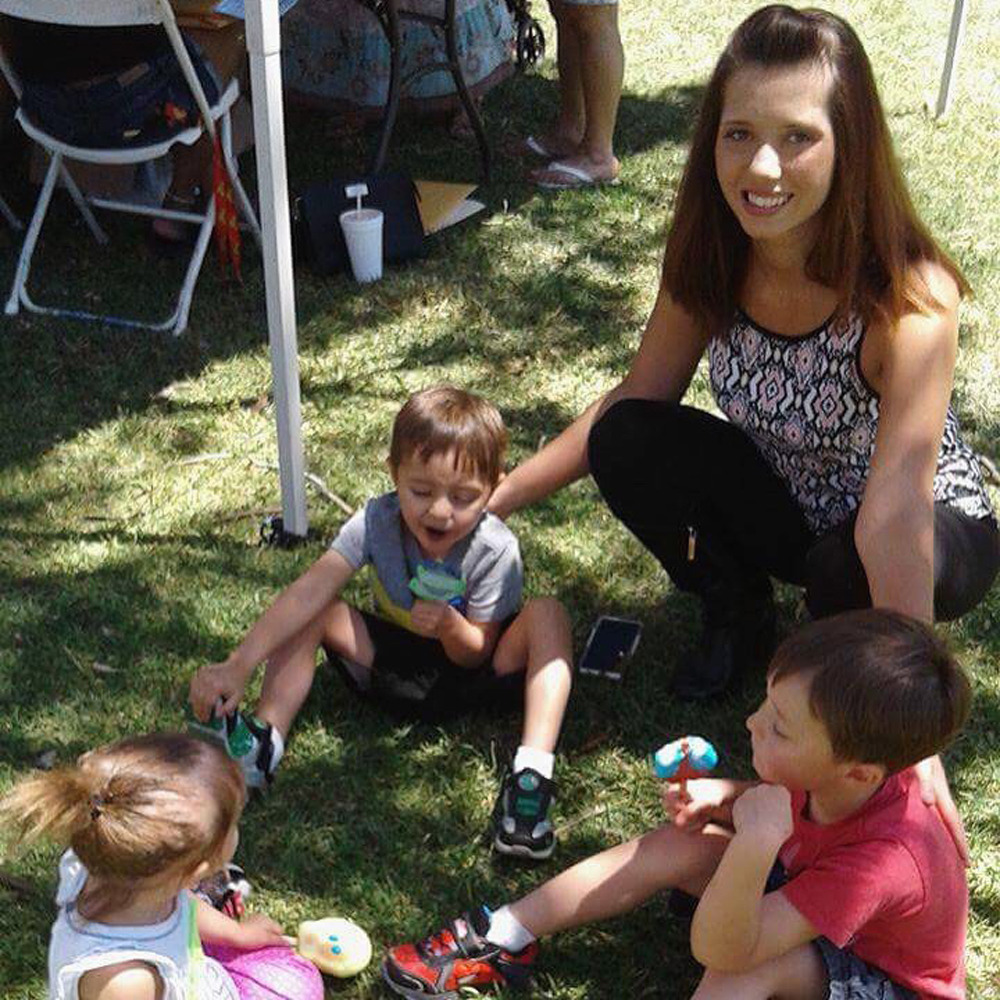

Destiny Adams was already caring for her own three children (left to right), Jordyn, 3; Jonathan, 5, and Jacob, 6, when her younger sisters needed a foster home.

LOS ANGELES — Destiny Adams was driving on Balboa Boulevard, on the way to visit her two younger sisters, when she got the call.

The courts had just ordered the sisters, Lisa, 13, and Nicole, 16 (names have been changed), to be removed from their father’s care. A social worker from the Department of Children and Family Services wanted to know if the girls could go to Destiny’s apartment or if they needed to find other placement.

I want them, Destiny said.

Just 22 herself and a single mother of three kids, she knew that bringing Lisa and Nicole into her small two-bedroom apartment in Stevenson Ranch north of the city would be a tight fit. Her only income is from child support — she’s in the midst of a divorce from her children’s father — and financial aid — she’s a full-time student at College of the Canyons. But as a former foster child herself, Destiny knew she would get a monthly stipend to care for each of her sisters.

What she didn’t know yet was that California’s ambitious Continuum of Care Reform (CCR), a statewide overhaul of the foster care system implemented in 2017, had one still-unresolved kink that would leave her without compensation for months. She would nearly lose her car, get threats from the bank that they were going to close her checking account and come close to getting evicted from her apartment on three separate occasions.

REFORM’S GROWING PAINS

Destiny Adams

(Left to right) Sisters Nicole, 16; Lisa, 13, and Destiny Adams. Destiny nearly lost her home and her car because of delays in getting monthly stipends to take care of her sisters.

In an effort to streamline the evaluation of a household’s fitness for a foster or adoptive child, California implemented a pilot project called Resource Family Approval as a pillar of its reforms. Rather than multiple processes of varying thoroughness for potential caregivers, the new process would offer a single, comprehensive standard including mandated foster parent training, psychosocial assessments and multiple in-person interviews, to be completed within 90 days.

“We want kids to get connected to people that they know as quickly as possible [after removal from their home], because we know that’s the best thing for the kid, psychologically,” said Angie Schwartz, policy program director at the nonprofit Alliance for Children’s Rights in Los Angeles. A relative or family friend “is likely to be the most stable placement for that young person; we know that from research.

“The reforms, at their core, are making sure that the system itself is child-centered and family-friendly, which is a fantastic goal,” Schwartz continued, “But then pieces of the reform, like Resource Family Approval, have been anything but child-centered and family-friendly.”

Families were eligible for funding only after successfully completing the RFA process, so even those families approved within the 90 days were liable to face three months of unfunded child care. For a low- or middle- income household unprepared to take in a grandchild, niece, brother or cousin, the burden of paying for food, diapers, clothes and other essentials sometimes meant that a child needed to be re-placed despite a relative’s best efforts.

And across the state, families were waiting for longer than the allotted 90 days: According to Department of Social Services data, in February of this year 41 percent of families were still waiting for approval after 90 days.

Los Angeles County faced a particular hurdle, approving only 5 percent of RFA applications within 90 days between CCR’s implementation on Jan. 1, 2017 through Jan. 31, 2018. Fifty-two percent of applications took longer than six months. That’s six months of paying out of pocket to keep a child — or children — clothed and fed.

“We had grandparents who had to say, ‘I can’t care for these kids anymore,’ and actually give up the placement because they couldn’t make ends meet,” Schwartz said. “We had people get actually evicted from their homes and lose their housing. And then the kids had to move because the caregivers they were with lost their housing.”

THE LA STORY

Destiny Adams

Nicole reads to Jordyn. The three children, two teenagers and Destiny are living in a small two-bedroom apartment.

Before the reforms, California’s Department of Social Services managed the process of licensing county foster homes in Los Angeles County’s immense child welfare system (the county was always in charge of approving relative caregivers). The reforms shifted that responsibility to the county’s Department of Child and Family Services, however, and complicated the relative caregiver approval process. This meant a high learning curve for social workers and a sea of red tape for DCFS to manage.

“We’re doing new work and we’re doing it in a new way, so it’s kind of like a double whammy for us,” said Brandon Nichols, chief deputy director of DCFS. The amount of work the RFA process entails was underappreciated by the state, he said, and so was the number of caregivers willing to step up and take in relatives on an emergency basis — a pleasant surprise, but one that created more RFA applications to process and added to the delay. The length of time kids were staying with relatives without financial help was unsustainable.

LA County’s temporary solution was to use a source of state funding designed to “enhance caregiver recruitment” as part of CCR, to be used at counties’ discretion. That allowed them to offer $400 per month per child for the first three months to families awaiting resource family approval. “We’re often placing children with relatives on an emergency basis, so if we have to remove a child from a mom or a dad we’ll be knocking on the door in the middle of the night,” Nichols explained. “We didn’t think that was fair to do without giving them some financial support to assist them.”

Those stipends were a big help to Destiny Adams when her sisters were placed with her, she said. “When they came to me they didn’t have clothes, they didn’t have backpacks, they didn’t have school supplies … I took them school supply shopping,” she recalled, “but as far as their monthly needs, we weren’t really making it.”

Alliance for Children’s Rights

Angie Schwartz

And the weeks were passing. Adams said she wasn’t told that she needed to apply to go through the RFA process until her sisters had already been with her for a month, and when she contacted the social worker she had been assigned to, the social worker told her that she was on leave and couldn’t help her.

The three months of stipends from LA County ended, and still Adams had no funding, she said. Her car was nearly repossessed, but she managed to hang on to it. She received three eviction notices, each time managing to scrape together enough money to make rent within the three days’ notice her landlord gave before she’d be out on the street.

Three more months passed.

Adams said she was approved as a “resource family” on March 2. She should receive back pay starting from her approval date (as of publication, she has received only one check for one of her sisters), but won’t get retroactive payments for the three-month gap between the three $800 monthly stipends ($400 per sister) and her approval date.

WHAT’S THE FIX?

First 5 LA

Brandon Nichols

On March 30, the California legislature passed Assembly Bill 110, a short-term urgency measure to provide the standard rate for emergency caregivers ($923 monthly per child) to families going through the approval process. The money isn’t available retroactively for any period of caregiving prior to March 30, however, and AB 110 will expire at the end of the fiscal year on June 30.

Plus, not all families get approved even within six months. Schwartz stressed that the bureaucratic machinery must make sure there is “no cliff that families fall off of. There should be no disruption in funding and support to these families.”

She is optimistic that a long-term version of AB 110 will be part of the governor’s proposed budget for the upcoming fiscal year. A proposal for such a long-term solution did appear in May in a revision of the budget, but limited emergency support to six months in the coming fiscal year, and just three months in subsequent years.

The Senate Budget Committee has recommended including language in the bill that accounts for families whose approval processes take longer than six months.

Meanwhile, DCFS is strategizing about how to reduce the RFA bottleneck, aiming to get through the current queue of families waiting for approval by September. The plan is to bring on 100 new hires solely dedicated to that task, Nichols said, and for every existing DCFS employee “from [DCFS Director] Bobby Cagle on down” to take on one case themselves.

And on April 10, the Senate Human Services Committee approved a bill, introduced by Sen. Holly Mitchell, meant to shorten the RFA process.

Destiny Adams had prepared written testimony for an April hearing at the California State Capitol: “Having been adopted by my grandparents & going through the foster care system myself, I know firsthand how much impact relative caregivers have on children’s lives.”

Laurie Shelley

State Sen. Holly J. Mitchell introducing Senate Bill 1083. The bill is meant to shorten the Resource Family Approval process.

She requested that the legislature “continue to provide funding at the time of placement beyond June 30 so that no family ever has to go through what I went through and ensure that if a long-term solution is adopted, there is no gap in funding when Assembly Bill 110 expires and the new, long-term solution begins.”

“If these requests become a reality,” Adams said, “families will be able to focus on what matters most: children — just like my sisters.”