NEW YORK — It was late in the evening on Feb. 16 when Joey Wong’s flight from La Guardia Airport in New York City landed at Fort Lauderdale Airport in Florida. Instead of going to his family’s home, he headed straight to his friend Robert Schentrup’s house. Schentrup’s sister, Carmen, had been killed two days earlier. She was one of the 17 slain by Nicholas Cruz when he entered Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida with a loaded AR-15.

The thought of someone walking into his alma mater with an assault rifle and slaughtering students in the hallways where he’d spent the majority of four years of his life was unfathomable.

“Thinking about it, it like shakes me to my core,” he said.

“Thinking about it, it like shakes me to my core,” he said.

Wong didn’t leave Schentrup’s house until 5 a.m. the next day. It was the first time the 18-year-old had consoled someone after a death.

The following days were a blur, he said. He slept little, ate poorly and spent most of his time with other Stoneman Douglas alumni who had returned. When the funerals were announced for Carmen and Nicholas Dworet, another victim Wong knew, he pushed back his return flight so he could attend them. At some point, he’s not sure when, he heard talk of plans for a March 24 event in Washington: the March For Our Lives.

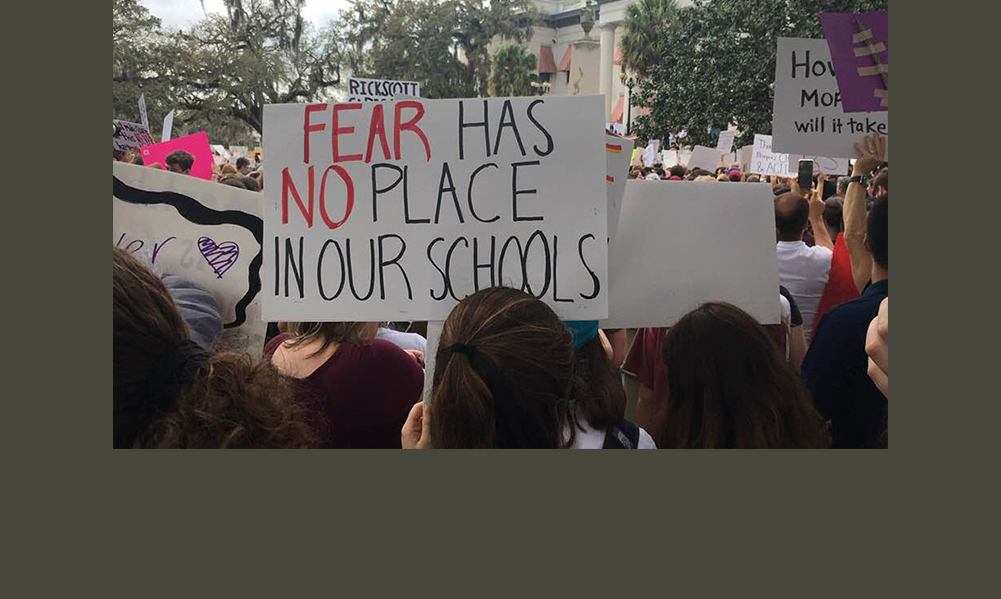

Even though the shooting took place in a tony suburb in Southern Florida, it has rallied high school students in New York City and other cities across the country to join the front lines of one of the nation’s most contentious political issues. Inspired by the fury of the young survivors of what is now knowns as the Parkland shooting, New York’s high schoolers and their supporters are working together to arrange transportation to Washington for would-be marchers. They are also planning a sister march in New York City for the same day for those who can’t make the trip.

Right now, there are nearly 30,000 people on the official Facebook page who plan to attend the march with another 86,000 who have expressed interest. In New York City there are nearly 9,000 attendees and 23,000 interested.

Wong, who wears a maroon Stoneman Douglas water polo team jacket around his neighborhood, took it on himself to help organize students at Pace University, where he is a freshman. He’s providing support to the New York City march organizers and working on transportation for the Pace students who want to march in Washington.

Wong, who has never participated in a march before, said he plans to march mostly with the Pace University contingent but will also spend time with his friend Robert Schentrup and other Stoneman Douglas alumni.

“These [New York] kids don’t know Douglas,” he said. “They don’t know Parkland. They don’t know Florida. So the fact that they are coming to D.C. to support this small little community means a lot and would say a lot.”

And the inspiration stemming from the Parkland survivors extends beyond march day organizing efforts.

Clarissa Sosin

Joey Wong graduated from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School and is close to families who lost children to the shooting.

Debates in class

Jessica Moskowitz, a student organizer for the New York City march and a sophomore at Yorktown High School in Yorktown Heights, Westchester County, said that one teacher brought up the shooting in class and said gun violence is a mental health issue. Nervous to contradict the teacher but feeling it needed to be said, Moskowitz, 16, said she raised her hand and brought up gun control.

Jessica Moskowitz, a 16-year-old student organizer, said, “We feel so passionately about (politics) but we haven’t really had the opportunity to act on it.”

What followed was a quick discussion about the two sides of the gun control debate. In the end the teacher disagreed, but acknowledged Moskowitz’s point of view. She was satisfied with the conversation. Her goal had been to make sure her fellow classmates understood both sides of the debate, she said.

“A lot of us kind of just take what our teachers tell us as the truth,” she said. “I didn’t want that to be the case.”

Moskowitz said she plans to march in New York City with her aunt and sister and is organizing a group of students from her school to take part. She’s never participated in a march before and is excited.

“A lot of the kids that I know that are involved in politics, we feel so passionately about it but we haven’t really had the opportunity to act on it,” she said.

Across party lines

Despite being in the forefront of a highly politicized issue, the young organizers said they want to keep partisan politics out of their fight.

“The first thing that I wanted everybody to know when I got into the group was I am conservative. I am a Trump supporter,” said John Papanier, a student organizer and a senior at Susan E. Wagner High School on Staten Island. “This is just something that should be nonpolitical and should be you know, human lives first.”

Except for one woman who responded to his post with an angry comment — and who then apologized later — Papanier, 17, said he’s never felt anything but welcomed by the group. He disagrees with Trump and the Republican Party on gun control, he said.

His family is conservative and Republican. His father is a retired police officer turned hospital security guard. His mother Kim Papanier, who plans to march with him, said the family has always been pro-gun, and they are supporters of the National Rifle Association.

The first school shooting Papanier remembers is Sandy Hook. He was around 12 at the time. While he didn’t comprehend what happened, he said, he did understand that someone had shot up an elementary school and killed children. He was horrified.

“After that I couldn’t think of school the same way,” he said. “I still haven’t thought of school the same way.”

Clarissa Sosin

Student organizer John Papanier is a Trump and GOP supporter, except on gun control.

Back to the school

Wong and his friends were coming back from watching the sunrise at the beach when they drove past the road that led to the front gate of Stoneman Douglas. It had been closed since the shooting so none of them had seen the school since.

That day, it was open.

They drove up to the gate and got out. Other than a few police officers and members of the media no one else was there. Standing silently with their arms wrapped around each other’s shoulders, they stared through the wire fence — not yet obscured by flowers and teddy bears — at the boxy building in the distance. A photographer captured the moment. The picture later aired on “The Daily Show.”

“I think we were lucky because we saw it as it was,” Wong said. “We just saw its bare fence, as we always saw it.”

Without the hustle and bustle of students the school was silent — haunting, he said. It was a beautiful day, but nothing could brighten the place up.

The group walked up to the yellow caution tape that marked the boundary of how far people were allowed to go toward the school. A police officer inched toward them, ready to stop them in case they tried to cross, but they didn’t try. They just stood there.

Eventually other people began to arrive. One woman approached them and told them she was sorry. Another woman stood by her car crying.

They got into their car and drove away.