Since the shooting last week at Rancho Tehama Elementary School in Tehama County, California, some schools across the nation seem to be on heightened alert.

Some are updating their safety plans and may be adopting elaborate safety drills.

But what about programs for young people after school hours?

How concerned should they be about the threat of a gunman? And what should they do?

After-school programs should consider the threat of an “active shooter,” but not focus on it, said Michael Dorn, executive director of Safe Havens International, a nonprofit that helps schools and after-school programs improve crisis preparedness.

“It seems like we’re seeing active shooter events left and right, but that’s been ongoing since the 1800s,” Dorn said. The number of murders in schools is just half of what it was 30 years ago, he said. Nonviolent deaths in schools are more frequent than violent ones, he said.

In 1958, 95 people were killed in an intentionally set fire at a Catholic elementary school in Chicago. In 1927, a local man bombed a school in Bath Township, Michigan, killing 44 people.

From 1998 to 2013, 62 people were killed by an active shooter on K-12 campuses, while 525 were killed in school bus accidents or by vehicles in the school parking lot, Dorn said.

When too much attention is focused on active shooters, people are likely to ignore the things that cause a lot more deaths, he said, such as medical emergencies and tornadoes.

“Fire is the most commonly used weapon of terrorists,” he said. So when there is an intense focus on barricading doors out of fear of a shooter, this could prevent safe escape in a fire, he said.

Create an emergency plan

A basic safety audit for after-school programs includes making sure a first-aid kit is accessible to all and that the program has a comprehensive list of students and their health concerns. But programs should also carry out and document regular fire drills and lockdown, earthquake and tornado drills.

Kenneth S. Trump, president of National School Safety and Security Services, a nonprofit safety consultant, agreed that after-school programs should consider active shooters but also think about other potential safety and security threats.

Program leaders need to assess potential threats, examine their physical settings, train their staff and know what to do should an incident occur, he wrote in an email.

He included the following steps:

- Evaluate your physical setting. This includes asking what potential hazards exist, such as nearby railroad tracks or chemical plants. Is the program isolated from others who might not see a need for assistance? Is it close to other programs whose problems could spill over?

- Plan and train with your staff.

- Create clear procedures.

- Provide good supervision of youth.

- Communicate safety and emergency preparedness expectations and have regular reviews of the plan.

After-school sites on school property

About 88 percent of schools have written emergency plans that include school shootings, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. But those plans may be inappropriate for an after-school program, such as when they direct adults to call the office in case of emergency.

After-school programs located on school property should make sure they know whether a school’s emergency plan applies to them.

An after-school program that has a contract with a school or district may be legally required to follow the school’s emergency plan, Dorn said. The after-school organization may not be aware of this — or even aware of the plan, he said.

“This is a common problem,” Dorn said. “Programs often have volunteers and a lot of turnover,” reducing staff awareness of the emergency plan.

For example, at Sandy Hook, one new teacher had not received keys to her door and had not been provided with the emergency plan, he said.

“Whatever plan you have, put it in your on-board process,” he said. It’s important for volunteers and staff to be trained in the plan when they first come to the program.

Some strategies

Safe Havens International has a list of 20 strategies that apply to after-school programs.

Among them are:

- Improve the ability of staff to address common medical emergencies.

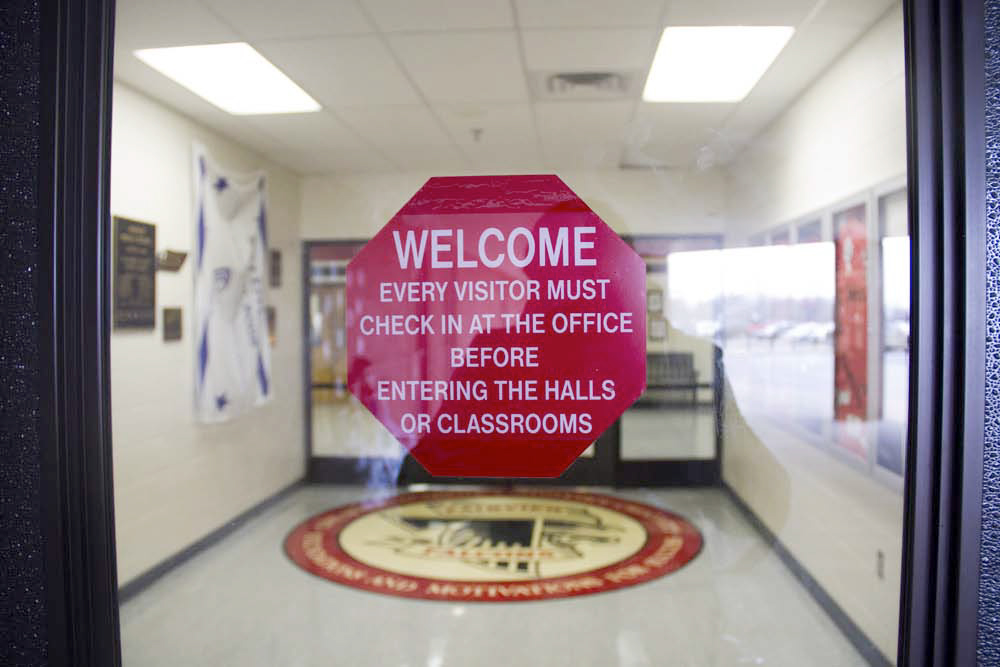

- Channel visitors through areas such as a main office where they can be observed by staff.

- Conduct an annual safety and emergency preparedness assessment. Local law enforcement, fire service and emergency management personnel can be a valuable resource.

- Add the following protocols to your emergency plan: reverse evacuation, shelter in place and “room clear.”

Important protocols to add

The lockdown is a crucial tool, Dorn said. It’s important, for example, if the threat is a child abduction by a noncustodial parent, he said. But it’s not the only tool.

Another important part of a crisis plan is a room clear, he said. This means students in one room are directed to leave the room and move to another designated space in the building. It can move students from an area in which an intruder is present or it can clear space for medical assistance.

Sheltering in place is important in the case of a hazardous material incident, he said.

Evacuating the building is part of an emergency plan, but reverse evacuation can be overlooked. A reverse evacuation quickly moves students inside when a danger exists outside, Dorn said. It must be practiced in order to be done effectively, according to Safe Havens.

A lot of times, children may be told to simply run, Dorn said. But running slows down evacuation in some conditions. It can cause bottlenecks at doors. And not every student has the capability to run, he said.

“What we teach is a brisk walk,” he said.

Dorn has worked on emergency plans with many after-school programs, including various Boys & Girls Clubs. After-school organizations can get assistance in developing an emergency plan by contacting their local or state emergency management agency, he said. FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, can also offer guidance.