LOS ANGELES — Imagine working hard to achieve your dream of attending the University of California at Los Angeles, only to find after getting in that your dreams may not come true after all. Sean Tan, 24, a UCLA public policy graduate student, knows that feeling all too well.

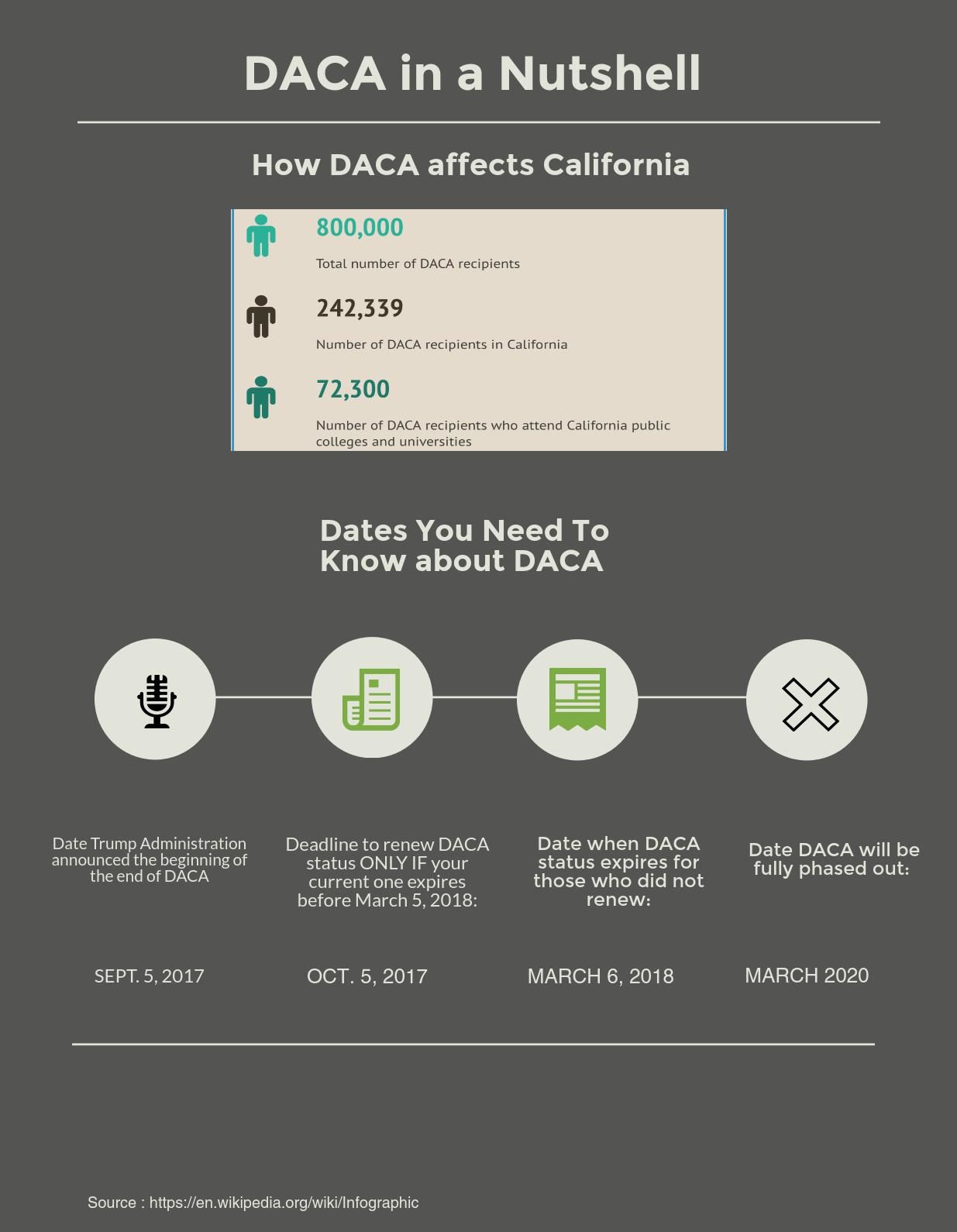

After President Donald Trump rescinded the order that set up the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, a policy aimed at young people who came to the United States illegally as children, Tan and other undocumented youth felt their futures suddenly become unclear.

Sean Tan

California is disproportionately affected by the DACA decision as it’s home to 242,339, or approximately 30 percent, of the 800,000 current DACA recipients. For California students like Tan, the thought of being deported to an unfamiliar country is unimaginable.

Tan is an undocumented Filipino immigrant who came to the United States when he was 11 years old. He did not become aware of his status until his freshman year in high school, when he and his peers began to discuss their college plans.

“Once I started applying for different summer programs, they started asking me for Social Security numbers and personal identification information that I didn’t have,” Tan said. “So I started to realize that I was different from my peers, that I had a different legal status.”

From the moment Tan learned of his undocumented status, he began volunteering for the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights in Los Angeles (CHIRLA), participating in civic engagement and partnering with community-based organizations. He also got involved with the New World Foundation and the Civic Opportunities Initiative Network. He applied for DACA status with their help three years later in the summer of 2012.

It was through these organizations that Tan was able to attend college at the University of California at Berkeley, then grad school at UCLA.

His leadership training at CHIRLA, which began his sophomore year of high school, helped him understand “what it meant to be undocumented, what it meant to be an immigrant.”

“I was very fortunate to have partnered up with the New World Foundation and CHIRLA,” Tan said. “They were actually the ones who had a structure to help you understand the process of applying to college.”

The programs Tan joined help undocumented students champion social justice activism and provide resources for students to attend college. CHIRLA, among other groups, was one of the early advocates for state Assembly Bill 540 of 2001, which allowed undocumented students to receive in-state California tuition.

The programs Tan joined help undocumented students champion social justice activism and provide resources for students to attend college. CHIRLA, among other groups, was one of the early advocates for state Assembly Bill 540 of 2001, which allowed undocumented students to receive in-state California tuition.

Tan advocated for the California Dream Act, passed in 2011, which provides state financial and institutional aid to public schools for any undocumented student. He says his motivation was solely to help his community and that it was just a plus that he was able to reap the benefits of his work.

Though DACA is not scheduled to be fully phased out until March 2020, those whose status expires before then will not be protected from that time on. Tan is one of the recipients whose status expires soon.

“As it stands right now, my DACA and my work permit will expire September 2018. And my [school] program doesn’t finish until 2019,” he said.

He’s worried that he may not be able to finish his program, and that he may even have to leave the country in the middle of it. “If nothing happens within these next two years, or even the six months that they promised … without a work permit, I’m unable to get a job.”

He and other DACA recipients must be proactive and seek out organizations to help them navigate the months and years ahead, he said. He aspires to work in the public sector in immigration and criminal justice reform.

Many colleges and universities have resources to assist students who currently attend school under DACA. The University of Southern California (USC) has an immigration clinic that works with members of the USC community to provide free emotional and legal support. Since its inception in 2001, the clinic has resolved more than 200 cases in immigration court, before the U.S. Court of Appeals or U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Emma Tehrani

“Our services are not limited to just people who themselves are directly affiliated with USC, but it’s also staff and faculty as well as their family members, so I think it’s a broader network than anybody realizes,” said Emma Tehrani, a clinical law student at the immigration clinic.

USC’s immigration clinic recently rolled out the Citizenship Project, which is a resource for people who are eligible to naturalize. Free English and civics classes are provided to help pass the test, as are citizenship clinics to help fill out the naturalization paperwork.

“The filing of paperwork itself is not that complicated,” Tehrani said. “It helps them immensely to have a legal representative fill them out with them to provide some of the basis and laws for some of those questions.”

DACA recipients have multiple free resources available to help ease the uncertainty that lies ahead. United We Dream, the largest immigrant youth-led organization in the U.S., has 55 affiliate organizations in 26 states and “advocates for the dignity and fair treatment of immigrant youth and families, regardless of immigration status.”

Dream Team LA is an Los Angeles-based organization that “aims to create a safe space in which undocumented immigrants from the community and allies empower themselves through activism and life stories.” It recently joined forces with UndocuMedia and the DRM Coalition for a national campaign to raise awareness of the $13 billion in U.S. taxes undocumented workers pay each year. The campaign can be found on social media sites under #WePayTaxesToo.

Many of these organizations say the end of DACA is where activism must start. The first item on their agendas is replacing it with permanent legislation.

California legislators in Washington have been active. Democratic Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard, ranking Democrat on the House Homeland Security Appropriations Subcommittee and co-chair of the Women’s Working Group on Immigration Reform, helped introduce the Dream Act of 2017 (HR 3440), a bipartisan bill allowing U.S.-raised immigrant youth to earn lawful permanent residence and American citizenship. She also helped introduce the American Hope Act of 2017 (HR 3591), which, if passed, will create a path to permanent legal status and eventual citizenship for DACA recipients and all qualifying Dreamers brought to the U.S. as children.

In efforts to get the Dream Act passed, Roybal-Allard pleaded on the House floor late last month, “If my Republican colleagues who say they want to protect our nation’s Dreamers — if that is true, this is your chance. … put our Dreamers on the road to the security and future they have earned in the only country they know, the United States of America.”