Over the past 14 years, I have spent thousands of hours working with teens in an anti-drug, anti-alcohol program and counseling young people who call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-8255). I have learned about the fragile, destructive — and often inappropriate — self-image too many young people embrace.

Over the past 14 years, I have spent thousands of hours working with teens in an anti-drug, anti-alcohol program and counseling young people who call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-8255). I have learned about the fragile, destructive — and often inappropriate — self-image too many young people embrace.

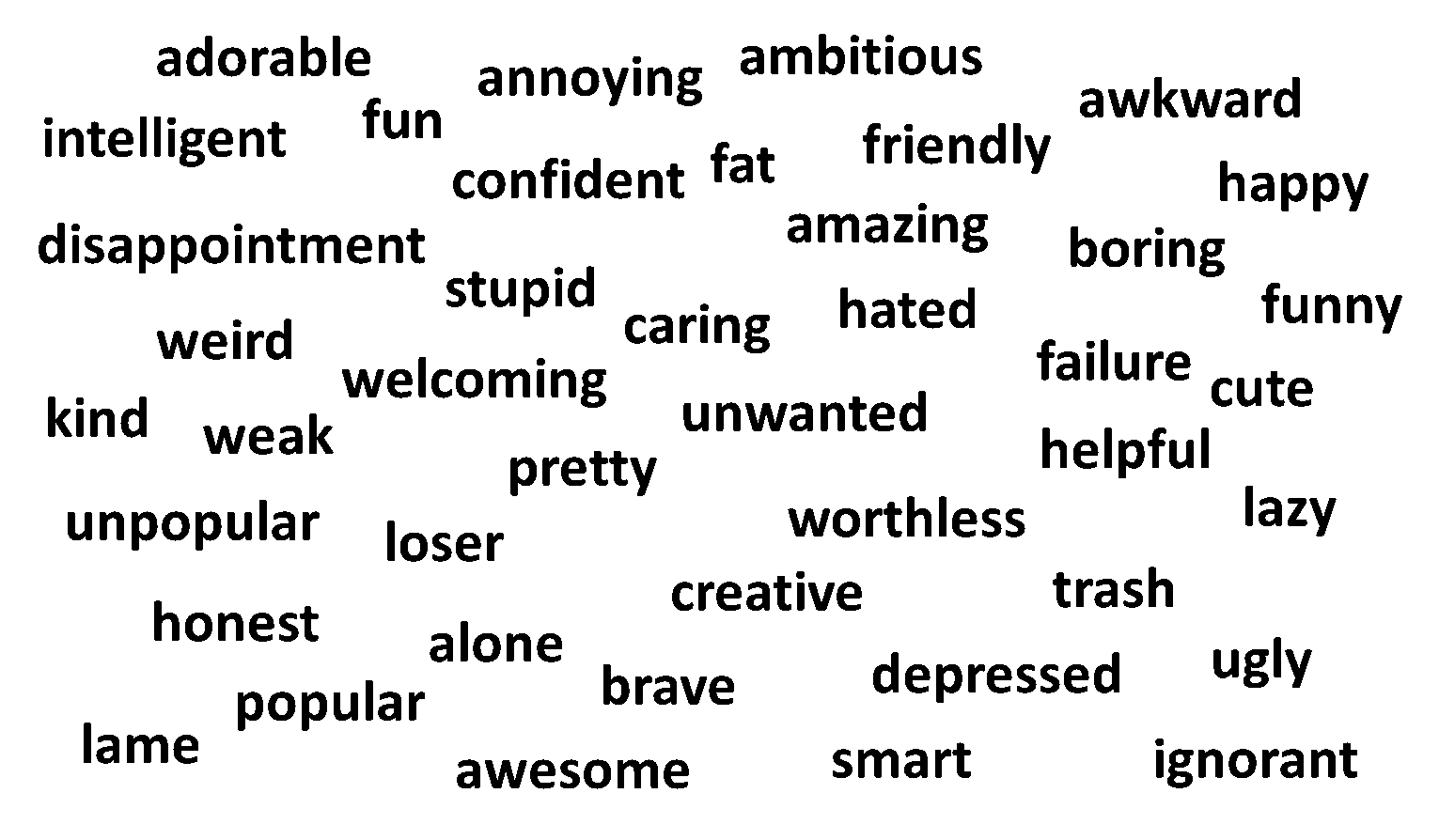

I have developed a simple tool helpful for any young person who struggles to find a self worthy of love and respect. Scan the words in the list below and choose three or four you might use to describe yourself. Once you have done that, think of a specific person in your life, someone who knows you and loves you — one I call a truth-teller — return to the list and select a few words they would select to describe you. Are your two lists the same? If they are, you are in the minority.

I have done this exercise with thousands, people of all ages, and it’s not unusual for more than 75 percent to admit their lists are different. Not only that, their self-description almost always contains more negative descriptors than the list they imagine a truth-teller would choose. That second list seldom includes anything negative. This is especially true for young people who are still early in their journey toward self-discovery. Their self-image has, too often, been battered by bullying, parental/societal expectations and the vagaries of technology and social media.

I have done this exercise with thousands, people of all ages, and it’s not unusual for more than 75 percent to admit their lists are different. Not only that, their self-description almost always contains more negative descriptors than the list they imagine a truth-teller would choose. That second list seldom includes anything negative. This is especially true for young people who are still early in their journey toward self-discovery. Their self-image has, too often, been battered by bullying, parental/societal expectations and the vagaries of technology and social media.

A number of years ago, I spoke with a high school senior who, during middle school, fell prey to a series of horrible influences. We nearly lost him. For unknown reasons, early in his high school career, he clawed his way out of the horrendous hole, forged an admirable academic record and was applying to college. I was taken by this incredibly strong, courageous young man. Yet, his self-description tore at my heart. Words like disappointment, weak, worthless and failure poured from him.

The human brain is a pattern-making marvel. Since we cannot possibly take in the nearly infinite quantity of visual, auditory, emotional, olfactory and sensory information with which we are bombarded every waking moment, we notice, and place in memory, a very limited amount, and use that filtered information to construct our view of the world … and of self.

We cannot see or remember every action we took, word we uttered or thought we experienced. Instead, we choose an extremely limited number of memories and use them to create a picture of who we are. Can you be certain you are choosing fairly? Are the snippets you choose weighted heavily by moments of embarrassment, sadness or pain? Many young people — perhaps most — as they construct a self-image, dwell more heavily on mistakes, missteps and suffering. The picture they create is of a human being defined by failure and pain.

When loved ones tell us who they see in us, they choose differently. They focus less on our failures. Why? Because they can witness our blessedness in spite of our humanness. “Everyone makes mistakes,” they would counsel. “Those missteps make you merely human, not a failure.”

In his heart-rending book, “Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption,” Bryan Stevenson documents his work with hundreds of people on death row. One thing he has learned from his immersion in the lives of those less fortunate is “each of us is more than the worst thing we have ever done.” When creating an image of self, if we remain anchored by the times we let ourselves down, we are being violent. We are our worst bully and say things we would never say to another human being.

When viewed in this light, young people can glimpse a self worthy of love. I often end presentations by asking participants to recall a truth-teller and write a love letter from that person to themselves. It is often life-changing. One young woman admitted she could use descriptive words for herself she had always reserved only for others. Another told me it was one of the most important things she had ever done.

In moments of deep sadness, I challenge young people to reach out to a truth-teller. “But then,” I counsel, “you need to do something truly courageous. Quiet the voice of denial, listen deeply to those who love you and believe that the portrait they paint is closer to what is real than a vision tainted by times when you were less than perfect and merely human.”

Roger Breisch has spent more than 3,000 hours answering calls on a suicide hotline for more than 14 years and more than 12 years working with a teen anti-drug, anti-alcohol program. His first book, “Questions That Matter,” was published by amazon.com on Aug. 1. You can learn more about his work at REBreisch.com.