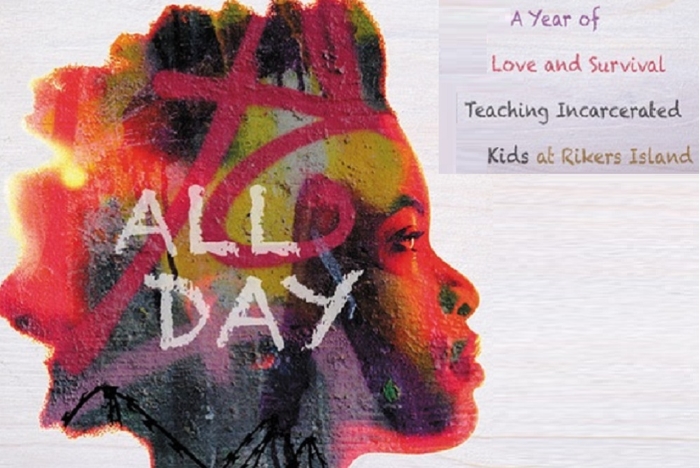

Liza Jessie Peterson’s “All Day” is a moving account of her career working with young men at New York’s notorious Rikers Island. Legendary in the world of detention facilities for its violence and brutality, Rikers is scheduled to be closed within the year.

Peterson’s career took a circuitous and surprising path. A high-fashion model working in what she described as a world of “luster and glam,” an actress, poet and playwright, she is hardly the stereotypical worker at Rikers. By her own account, she “stumbled” into teaching incarcerated boys as she searched for a steady job. She also thought it would be a temporary one, but it turned into an 18-year career (so far). This book is about what she experienced in that first year as a GED (General Education Diploma) teacher.

Though flawed in some fundamental ways, the book is much more than a modern-day version of “Blackboard Jungle,” or “To Sir with Love.” But all three share themes of idealism, commitment and racism, offering a fascinating comparative history of the evolution of inner-city education and its attendant problems.

Peterson’s account of her first year of teaching is so much more raw and personalized in its violence and racism than these earlier accounts of school mayhem. Part of that is due to the communications revolution, which has given us a different level of awareness. Technology has made bullying, for instance, more widespread and often psychological.

Peterson correctly, I think, clearly describes the significant failings in both the criminal justice and prison systems. Cogent examples of racism, inequality and sentencing abound as greater numbers of minority teens are given stiffer sentences than their white counterparts. Poor and minority young people are simply treated far worse than those who are white and /or of means. Public defenders are overworked and often meet their clients for the first time at a court appearance.

Peterson clearly points out the injustices and inequalities that permeate the system. Likewise, she vividly portrays the inherent violence and sadism that exists in the prison system itself. For-profit prisons are an outrage. Certainly, correction officers have a difficult job, but the prevalent lack of humanity is palpable. Peterson’s portrayal of her role as mother, older sister, confidante, fantasy is insightful as well.

Her biggest shortcoming is her analysis of why the system has reached this abysmal level. I submit she has a somewhat distorted view of how all-pervasive racism impacts the system, and unfortunately this detracts from the book’s efficacy. In the interest of full disclosure, this reviewer is white and admittedly have never been stopped by the police for DWB (driving while black). But I have lived for the past decade in an area that is about 90 percent black, and worked for four decades in a similar arena.

Peterson is obsessed with racism, which obviously still exists in America and is certainly a significant factor throughout the prison and justice systems. She seems to be obsessed with ubiquitous references to “a century old system of slavery … that has gobbled up black and brown people at a dizzying rate … and the need for the liberation” (an interesting choice of words) “of a marginalizing community.”

This single-cause perspective distorts the reality of the multifaceted causes of the current educational crises, which exist far beyond minority communities too. Certainly Peterson is correct that incarceration rates of alleged black perpetrators are dramatically higher than for the population at large. An egregiously unfair sentencing system exists. The educational system lacks a legitimate national commitment to high quality

American society has made some progress in the past 50 years in alleviating bigotry and racism, but obviously it still exists. Leveling the playing field, especially institutionally, has made some progress, but there is still a long way to go. Accusing American society of white supremacy, even though it may exist at Rikers, overstates and oversimplifies the problem. Getting the hearts and minds of many is the next vital step to make this society a legitimate rainbow — we still have a long way to go.

Jackie Ross is an experienced social worker with urban, disenfranchised youth, lifelong child advocate and community activist. She is the founder and director of The Foundation of Hope, a 501©3 in New Jersey, that is being reorganized to concentrate on advocacy for those in need. She is writing a book about an international advocacy case she coordinated.