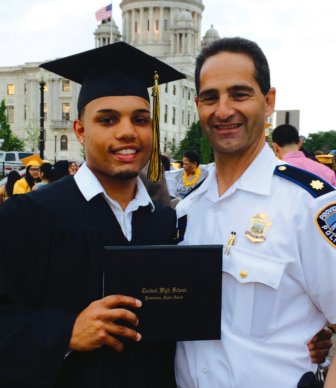

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE RHODE ISLAND MENTORING PARTNERSHIP

In many cases, simply by being present mentors are helping bridge the opportunity gap, according to the Rhode Island Mentoring Partnership, which trains mentors like Carlos Zambrano — with mentee Brendan — in what it takes to be a quality mentor. Training topics range from communication and child development to cultural competency and goal setting.

WASHINGTON — As the gap between the nation’s poorest and wealthiest citizens has grown during the past four decades, so has the gulf in opportunities. Middle-class parents are happy to pay for SAT tutors, drive the neighborhood team to soccer practice, read to the kids before bedtime and send them to camp each summer.

For those in the nation’s poorest communities, those opportunities seem like fantasy. And those who have a parent or sibling in prison or fighting health and mental health problems have longer odds of catching up with those who have means.

By the time children reach sixth grade, “middle-class students have spent 6,000 more hours in learning activities outside school than students born into poverty,” according to a 2015 study by the Harvard Family Research Project. High-income parents spend seven times as much money on out-of-school enrichment activities — such as zoos and museums — than lower-income families, the study found.

The task of bridging that gap and creating opportunities for all children has been filled by nonprofit organizations, teachers, mentors, mental health professionals and others, often bolstered by federal dollars. Working with families and helping children known they are supported and loved is an important step to helping them break a cycle of poverty, those experts said.

“Of course, these kids and their families need shelter, food, maybe drug or mental health treatment, but I think we all realize real efforts need to be made to provide them a different way of life or they won’t get out of this cycle [of poverty and abuse],” said Jo-Ann Schofield, president and CEO of the Rhode Island Mentoring Partnership. “If you only know what you are seeing around you every day, you don’t know there is anything better out there and another way to live. In our case, we try to provide positive role models and mentoring. There’s just a general understanding now that helping kids get real opportunities goes beyond just providing them the basics.”

Supporters on both sides of the aisle

In recent decades, through two Republican and two Democratic presidential administrations, supporters of child welfare and anti-poverty measures have relied on federal government funding and initiatives to help close that gap, or at least give low-income families a fighting chance. For the most part, these advocates said, both parties have agreed on the need to help children and have put tax dollars behind those efforts. Their approaches differed, but not their commitment to providing services low-income students could never get on their own.

But advocates, those who run social programs aimed at helping children and lobbyists seeking congressional support for those programs, say they worry that could soon change. A budget blueprint put out by President Donald Trump and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney threatens some of the most successful and universally supported programs, including one directly supporting juvenile literacy, another that provides teaching and after-school programs for low-income students and their families, and food programs for low-income families.

Among the cuts, the budget proposal would eliminate funding for 21st Century Community Learning Centers, which is the only federal funding for summertime learning, and before- and after-school educational programs for low-income students. The budget proposal also seeks to end grants to train teachers and money earmarked to help low-income children get college degrees.

In each case, the White House budget blueprint asserts the programs don’t help or have not provided any real value.

“That is flat wrong. I don’t know whether the budget director doesn’t know what he is talking about, or that he just doesn’t care,” said John Gomperts, president of America’s Promise Alliance, a nonprofit that has no federal funding and says its mission is to help “create conditions of success for all young people, including the millions currently left behind.” (See Opportunity Gap, page ?.)

“Those are evidence-based programs,” Gomperts continued. “Of course, we all agree that things that don’t work should not be funded, but you shouldn’t say things don’t work when the evidence is so strong that they do.

“The anti-factual part of this debate bothers me,” he said. “Going back to the first President Bush, there has been bipartisan agreement on the importance of funding programs that provide opportunities for children. There were disagreements on the best approaches, of course, but both parties always agreed on the basic importance of providing these services.”

Government funding attracts private donors

In the White House’s 2018 budget proposal and in speeches, Mulvaney has consistently said that federal dollars can be replaced by the private sector and charities. But executives of nonprofits and program directors said that the federal money, which often makes up only a small portion of an organization’s budget, provides an impetus for the private giving.

“The government funding should be considered an investment, and those investments are in and of themselves the safety net. Federal funding provides seed money and credibility that can be leveraged for all the private-sector donors to rally around,” said Erik Peterson, vice president of the Afterschool Alliance. “In many cases, it’s a small amount of money, but it brings legitimacy to the table.”

The funding brings tangible benefits to low-income families, according to advocates and studies. According to the Mentoring Effect, a national survey conducted by MENTOR: The National Mentoring Partnership, young people with mentors are:

- 55 percent more likely to be enrolled in college than youth without a mentor.

- 81 percent more likely to be involved in extracurricular activities

- More than twice as likely to hold a leadership position within those activities.

“There is no doubt that after-school programs and food programs help close the opportunity gap,” Peterson added.

For six years, Providence, Rhode Island, Deputy Police Chief Thomas Verdi (right) mentored 19-year-old Rommy (left), and is now helping to introduce a voluntary mentoring program in his police department.

Mentoring: In everyone’s best interest

While the White House budget proposal has concerned many advocates, many said they are hopeful that long-time allies in the House and Senate will maintain the federal commitment to supporting Out of School Time programming.

“There is this shared notion in Congress and among the public, that a great commitment to kids is in our national self-interest,” said Gomperts, from America’s Promise Alliance. “People who pay attention know that The Boys and Girls Club is a great thing. They know after-school programs and making sure kids have food and a place to live is good. It goes beyond compassion, which is so patronizing. It’s good for the future of the country.”

Advocates are already pooling efforts and coming up with strategies to win congressional support. Pediatricians are being asked to explain the benefits of nutritional programs, police agencies are providing stories of lower crime in areas where strong after-school funding is in place. At its annual convention in Washington, D.C., earlier this year, The National Mentoring Partnership arranged for its members to lobby both houses of Congress to increase the federal budget for mentoring programs from $90 million to $120 million.

Providence, Rhode Island, Deputy Police Chief Thomas Verdi has a unique knowledge of the benefits of mentoring and other programs aimed at low-income children in closing the opportunity gap. For the past six years he has mentored a young boy and is now helping to introduce a voluntary mentoring program in his police department.

Verdi spent 10 years sitting on the Rhode Island Parole Board, which he said provided insights into the best way to help offenders restore their lives.

“If you want to reduce crime and recidivism, it’s pretty basic. Kids need a place to sleep and a roof over their head. If they have any trauma or mental and drug issues, they need proper treatment,” Verdi said. “They need a place to go after school, so they aren’t idle and getting into trouble.

“The fourth factor, and few people know this, is they need someone influential in their life who can act as a mentor and role model. For most families, you have a stable environment of aunts and uncles who influence you. Not all kids have those same opportunities,” Verdi said.

Mentoring helps provide those opportunities, Verdi said. He and his wife have been sponsoring children who need a helping hand since 1990, but he only formally became a mentor six years ago when he began meeting with 13-year-old Rommy. He has seen the impact on both their lives.

“It’s extremely rewarding when you can help somebody who likely would have wound up in prison or living in poverty for his or her life, but is now in college, employed and having positive relationships,” Verdi said.

“Look, you can have a mother or father who is trying hard, but life in the inner city is very, very difficult for many,” Verdi said. “Even if you have good parents, it doesn’t mean you won’t benefit tremendously if you have a mentor to talk to after school or when things are tough.”

The National Mentoring Partnership said on its website that the need for mentoring programs goes well beyond the inner city, benefiting children in rural and remote areas where services and anti-poverty programs are sparse.

“Young adults who are in danger of falling off track” are 55 percent more likely to enroll in college if they have a mentor, the organization said.

“Students who meet regularly with their mentors are 52 percent less likely than their peers to skip a day of school and 37 percent less likely to skip a class,” according to a study of the Big Brother/Big Sister Program that the Mentoring Partnership cited on its website.

Mentor Kathleen Ferriera and her mentee Jesse are part of Rhode Island Mentoring Partnership’s direct service programs which, combined, serve about 350 kids.

Schofield said her organization works with 60 mentoring organizations in Rhode Island, serving 5,000 kids. Finding enough mentors is difficult, and she is now working on a training program with Community College of Rhode Island.

“Recruiting volunteers is the hardest thing, and we’ve been lucky enough to get a grant from the United Way focusing just on this,” she said.

“What you have to remember is that the component for needing a mentor isn’t just being a young person, it’s feeling isolated,” Schofield said. “My kids and most kids, have coaches and teachers that were positive influences in their lives. But so many of young people today don’t have that one person they can turn to.

“Once the kids get into the mentoring program, and start working and trusting their mentor, we start hearing the same thing from them.,” Schofield said. “They say, ‘I didn’t know I could just ask.’”