LOS ANGELES — Marbella Munoz was a foster child for most of her life. As is true for many foster children bounced through multiple placements, she was frequently forced to change schools. Despite the repeated changes, Munoz said she managed to keep up her grades. When she was 17, school administrators told her she had been referred to a program called “school-based supervision.” The “supervision” was not provided by a school guidance counselor or a teacher but by a juvenile probation officer.

Munoz didn’t understand. “Although I was an ‘A’ student, I was referred to a probation officer at my high school who told me I would have to be on their caseload because I was changing schools too much,” Munoz said.

Munoz didn’t understand. “Although I was an ‘A’ student, I was referred to a probation officer at my high school who told me I would have to be on their caseload because I was changing schools too much,” Munoz said.

The girl explained to the officer that the transfers were outside her control. “But I was told I had no option,” she said.

Upset that she was on what appeared to be juvenile probation, although she’d done nothing against the law, Munoz at first refused to report to her assigned deputy probation officer. Then she dropped out of high school altogether. (She now attends the Youth Justice Coalition’s FREE L.A. High School.)

Munoz’ story comes from a new report, titled “WIC 236: ‘Pre-Probation’ Supervision of Youth of Color With No Prior Court or Probation Involvement,” that examines and analyzes a controversial youth crime prevention strategy run by the Los Angeles County Probation Department, the nation’s largest juvenile probation system.

The program, known unofficially as “voluntary probation,” assigns children 10 to 17 considered by the county to be “at risk” to a professional probation officer, with their parent or guardian’s permission.

Like Munoz, the kids referred to voluntary probation have broken no laws and have no history of court or probation system contact.

Patricia Soung

The report — authored by Patricia Soung, senior staff attorney for the Children’s Defense Fund-California; Kim McGill, organizer for the Youth Justice Coalition; Josh Green, staff attorney of the Urban Peace Institute, and Bikila Ochoa, policy director for the Anti-Recidivism Coalition — echoes concerns expressed by youth advocates and, more recently, by LA County’s probation commissioners at several meetings this year.

So, should the LA County Probation Department be putting kids who have never been in the justice system into a program that resembles court-ordered probation, without the court order?

This report suggests the answer is a resounding NO.

‘Voluntary participation’?

Jocelyn Mateo, Munoz’s classmate at her alternative high school, had also been referred to a probation officer although as far as she knew she’d done nothing wrong.

“On my first day in the tenth grade at my new continuation school,” Mateo said, “I was pulled out of class and brought to the probation officer’s (PO) office.” Mateo was frightened that something had happened to her family “because there was no other reason I should be seeing a PO,” she said. She had never been arrested, never gone to court. “I asked the PO what had happened, and he told me that my name was on some list, so I had to see him. I asked him why my name was on the list and he refused to tell me.”

When she got home that afternoon, Mateo told her mother about her disturbing encounter. “My mom knew nothing about the PO and didn’t understand why I had to see one,” she said. “It made me feel like I had been labeled a monster child, a future criminal. I felt like the school, the PO, was just waiting for me to mess up. I felt like I was being set up for failure.”

Within days, Mateo, like Munoz, dropped out of school.

The pool of Los Angeles County youngsters who wind up in voluntary probation are called “236 youth,” in reference to the LA Welfare and Institutions (WIC) Code 236, which permits contact by county probation departments with at-risk youth, despite the lack of a court order.

LA County Probation defines at-risk youth primarily as those who live in 85 communities that are labeled the “most crime-affected” neighborhoods. A youth is also defined as at risk if he or she demonstrates two or more problems in the following areas: “family dysfunction (problems of parental monitoring of child behavior or high conflict between youth and parent), school problems (truancy, misbehavior or poor academic performance), and delinquent behavior (gang involvement, substance abuse or involvement in fights),” according to the report.

Once youth are labeled at risk, they can be referred to probation for non-court-ordered supervision, as long as they have no prior probation involvement, and as long as they participate voluntarily.

But, as the cases of Marbella Munoz and Jocelyn Mateo suggest, “voluntary participation” may be very loosely defined.

According to internal LA County Probation documents, the purpose of the program, which is in 103 LA County high schools, and 38 middle schools, is to provide services “designed to prevent at risk youth from becoming involved in juvenile delinquency and having law enforcement contact.”

Which kids are sent to voluntary probation, why?

Contrary to the document’s stated reasons for intervention, more than 85 percent of youth in the program were not referred because of traditional warning signs such as aggressive behavior or a history of discipline problems, the report found. Instead, it was due to school-related issues such as low motivation in classwork, poor attendance, a drop in grades or a related behavior issue having to do with school or school performance. This is concerning, the five authors noted, considering statistics that show 87 percent of youth in LA County’s juvenile justice system have a learning disability.

Only 5 percent of kids were referred for more risky behaviors such as substance abuse, problems with anger or parental conflicts.

In 2016, none of the 236 youth were referred to school-based supervision for gang involvement or fighting, although 18.3 percent of the services reportedly offered to them were labeled gang intervention, the report shows.

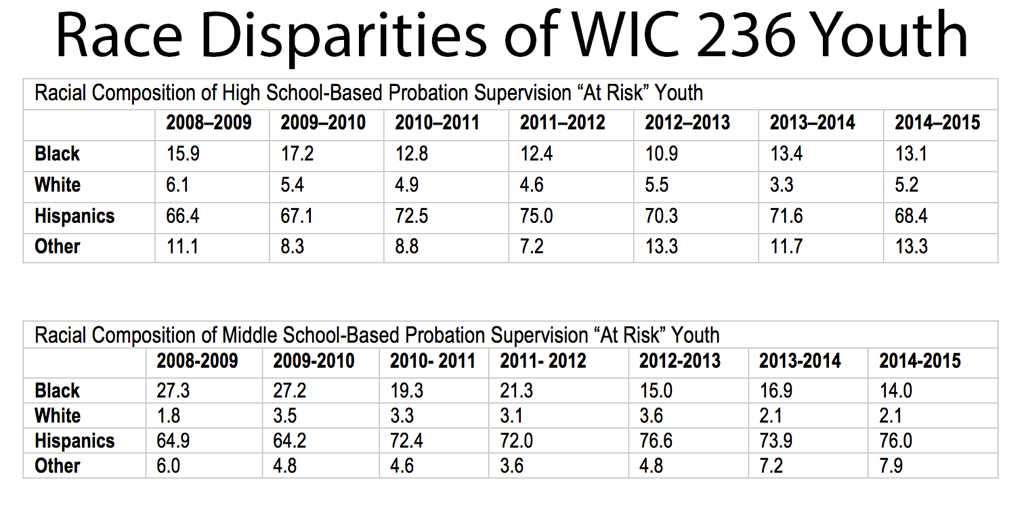

Moreover, students who are referred are disproportionately minority youth. In 2015, according to the report, 13.1 percent of LA high school students in voluntary probation were black — nearly twice the 7.4 percent of black kids in LA County as a whole. The ratios were similar when looking at middle school students.

Interestingly, the overall numbers of young people under formal supervision of the LA County Probation Department have taken a steep dive in the last 10 years. Yet, as of fiscal year 2013/2014, for the first time youth on voluntary probation outnumbered those mandated to be on probation. By FY 2015/2016, the number of at-risk youth in voluntary probation was more than double that of those formally on probation, at 4,752 and 1,990 respectively.

Considering the steady decline in juvenile crime, along with increased evidence that therapeutic and community-based programs are far more effective than programs that involve law enforcement, it is difficult not to ask why the number of youth who are unofficially supervised by the largest probation department in the nation is increasing.

Terri McDonald

This system is one of a long list of problems that LA County Probation Chief Terri McDonald inherited in January from the previous administration and is now feeling increasing pressure to fix.

McDonald and her second-in-command for juveniles, Chief Deputy Probation Officer Sheila Mitchell, said at a March meeting with the LA Probation Commission that the program was under review in the hopes of improving its work with at-risk youth.

Bulk of funding goes to salaries, benefits

California’s legislature began setting aside millions of dollars a year for youth struggling with delinquency under the state Juvenile Justice Crime Prevention Act (JJCPA), passed in 2000.

The approximately $31 million that LA County receives yearly from JJCPA is specifically designated for local programs aimed at keeping kids who have tangled with the juvenile justice system from returning, and to help kids at risk of winding up in the system from entering it in the first place.

But when it comes to what LA County has spent of those millions on WIC 236 kids, the report found the largest chunk is not being allocated for juvenile programing that has been proven to produce measurably positive outcomes for at-risk youth. The biggest slice of the pie — 90 percent — helped pay salaries and benefits for the county’s school-based juvenile probation officers from 2012 through 2015. During that same time, only 1.2 to 1.8 percent of the money earmarked for voluntary probation went to community-based organizations, which have proven methods of helping kids in concrete ways with their challenges.

Under the regulations governing the fund, only about .5 percent of the JJCPA dollars is supposed to be spent on administrative costs such as salaries for probation personnel.

Similarly uneven spending percentages held true for fiscal year 2012/2013 and 2013/2014.

In dollars and cents, this meant that $6,986,194 was spent on probation salaries for FY 2014/2015 and only $134,329 was left over to actually provide services to kids.

Probation had a different set of calculations in a spring 2017 report, which computed the overall cost of probation services for WIC 236 youth as $11,192,960 for 7,560 youth, which meant a cost per kid per annum of $1,480.55. Out of that per capita dollar figure, the cost for staff alone was about $1,017 per year — or 69 percent of the whole.

Whichever system of calculations one uses, it is clear that the lion’s share of the money budgeted to help kids on voluntary probation is not going to programming for the kids themselves, but to pay the officers to whom they are assigned.

What do kids on voluntary probation receive?

So what do the kids on voluntary probation get for the money spent on them?

LA County’s Probation Commission, an advisory body that officially monitors the probation department, asked for answers to that question at their March 9 meeting.

Probation department representatives gave the commissioners a report that covered the broad strokes of how the program works, but not which program providers work with the 236 students, or specifically what services those kids are getting.

The biggest category of services listed in both the WIC 236 report and county-generated reports is “tutoring.”

In a 2016 snapshot report, 30.8 percent of the voluntary probation kids were getting tutoring, which the report’s authors saw as a red flag. “Typically,” they wrote, “probation officers have neither the training nor expertise … to effectively work with youth struggling with academic or behavioral issues.”

Their next conclusion was even harsher: “[Probation’s] expansion into youth development and education work also reflects a broad dismissal, and perhaps even distrust of, people specially trained to do that work.”

The report noted studies like a 2009 20-year study by University of Montreal and University of Genoa researchers, and a 2014 University of California, Irvine dissertation, among several others, suggesting that juvenile probation, and even lighter-weight contact with the juvenile justice system, leads to much higher odds that a kid will have another brush with the law than there is for similarly situated kids with similar behavior, who have no system involvement.

How does county know if program is working?

Near the end of the WIC 236 report, the authors ask some pressing questions: Does this program work? Does it benefit the kids involved? What kind of outcomes are measured to determine if this method of voluntary probation has a positive effect on the kids involved?

Diwaine Smith, another youth quoted in the report, had a bleak perspective.

Smith is now a community leader with the Youth Justice Coalition, and a co-founder of Long Beach’s Men Making a Change program. But in high school he was on formal probation, which he said gave him an informed perspective on the kids on nonformal probation.

He described a “police bungalow” on his high school campus that also contained the school’s probation office.

“Since I was on formal probation, every day during my 45-minute lunch break, I had to walk to the police building, sign my name on a sign-in sheet and leave,” Smith said. “Some days I saw my probation officer as I signed my name, some days I saw a police officer instead. We didn’t talk. I just signed my name and left.”

During those daily trips to the police building, Smith said he noticed students there “who had never been in trouble before, who weren’t on probation.” When he asked what the non-in-trouble kids were doing in the police bungalow, he was told they too had to check in and sign their names.

“Making these kids report to the police office sent a wrong message to them, and to the rest of the students who saw them go there every day,” Smith said. “It sent a message that they could go to jail.” It would have been better, he concluded, “to have them see teachers or therapists who knew them, could maybe see changes in their behavior and do more to help them.”

On the data-driven side of the question, the RAND Corporation has been assessing outcomes for the program since approximately 2001. But according to the report, with a few exceptions, all RAND does is measure any improvement or backsliding in what is known in the world of the Board of State and Community Corrections as the “Big 6” outcomes, namely 1) arrest rate; 2) incarceration rate; 3) probation violation rate; 4) probation completion rate; 5) restitution completion rate, and; 6) community service completion rate.

Since, by definition, the 236 kids haven’t been arrested, incarcerated, put on formal probation and/or been sentenced to do community service or to pay restitution, this kind of measurement is “inapplicable,” the report states.

And in addition to being “meaningless data points,” the report’s authors write, “they also reveal a criminalizing frame for youth who have had no system contact and who have almost entirely been referred for school-based needs.”

At the same time, other more relevant measurements of progress, such as “improved educational attainment, increased pro-social skills, improved relationships and connection to positive peers, family and community,” are simply not collected.

Probation spokesperson Kerri Webb said the evaluation side of the equation will soon be changing. “We’ve contracted with RDA [Resource Development Associates] to evaluate all of our JJCPA-funded programs, and 236 is funded in part with those funds,” she said. “They will report findings to us.” Webb also said the department is “evaluating the entire program and that also includes salaries.”

Cyn Yamashiro

Cyn Yamashiro, the directing attorney for the Independent Juvenile Defender Office of Los Angeles County, and also a member of the probation commission, said that, in the last few months, the voluntary probation program has raised a lot of concerns among the commissioners.

“I don’t think that anyone could make a coherent argument,” he said, “that if some competent adult out in the field learns that a kid is engaging in risky behavior, if there are resources available, the adult should connect that kid or his family with any resources that can help him navigate whatever challenges he’s facing. There’s no disputing that.”

The question, according to Yamashiro, is “whether or not the [probation] department is the entity that should be doing it. In a landscape of scarce resources, is it the most fiscally effective policy,” or humanly effective, “for probation — which is law enforcement — to be engaging in that type of outreach.

“In my opinion,” he said, “the answer is no to both questions.

“All the data shows that interaction with the juvenile justice can be counterproductive, and that the longer that they’re involved the harder it is to get them out.”

When compared to “other kinds of interventions in the community that don’t involve law enforcement,” the programs without law enforcement are more effective, he said.

The good news, according to Yamashiro, is that “the powers that be are recognizing this. [Chief] McDonald and [Chief Deputy Probation Officer] Mitchell are both smart people. They understand the issue, and after hearing their responses at our meeting, I have the feeling they intend to move this in the right direction.”

This story is part of a series by reporters from the USC Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism, and is the product of a collaboration between the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange and WitnessLA.

This story has been updated.