Photos courtesy of High Desert Leapin' Lizard

After a STEAM unit in which kids learned about the human body and the benefits of exercise, parents joined kids in outdoor play at the High Desert Leapin’ Lizards after-school program in Inyokern, California. The town of 700 is located in the high desert area of California.

Earlier this year, students in the High Desert Leapin’ Lizards after-school program in Kern County, California, got a glimpse of life on Mars. They took part in a videoconference with NASA Digital Learning Network Specialist David Armstrong, who talked about what it took to survive on the red planet.

The videoconference was an intentional strategy to bring learning opportunities to kids in their rural community.

In this rural part of California, “we have to get our resources digitally,” said Curriculum Coordinator Jennifer Worley, because there are fewer educational and cultural institutions in the immediate area.

Leapin’ Lizards operates two school-based sites in the town of Ridgecrest, population 28,400, and one in Inyokern, population 700, just 125 miles from Death Valley.

Leapin’ Lizards faces many of the challenges that the nation’s other rural after-school programs face, including a higher poverty rate.

“We have kids who have never left our small town,” Worley said.

Rural poverty means inequality

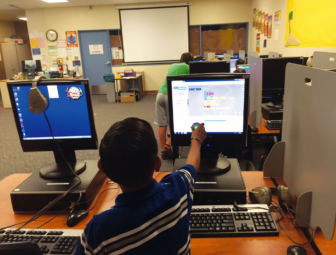

Students in the High Desert Leapin’ Lizards after-school program at Theodore H. Faller Elementary School in Ridgecrest, California, program tiny robots called Ozobots to dance, using the Ozoblockly drag-and-drop editing program on their computers.

Three years ago, Joel Kotkin, professor of urban studies at Chapman University addressed the issue of opportunity in a Forbes magazine blog.

“Perhaps no place is inequality more evident than in the rural reaches of California, the nation’s richest agricultural state,” Kotkin wrote.

Fully one-third of the 83,000 children

in Kern County live below the poverty level, according to a 2016 report card by

the Kern County Network for Children. And the poverty rate is rising, not lessening, since the Great Recession, according to the organization.

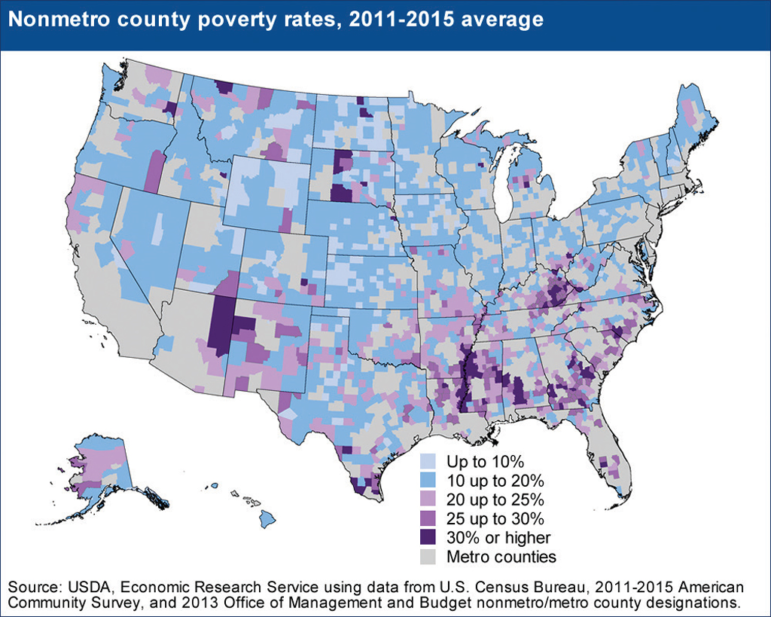

The nation as a whole is rebounding from recession. High school graduation rates are rising. The teen pregnancy rate continues to drop. But one-fourth of children in rural areas live in poverty compared with one-fifth of children

in urban areas, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. And areas of persistent poverty are a big issue.

Rural poverty is concentrated in the southern United States in areas like Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture and American Community Survey data.

It’s also concentrated among the Hispanic population in parts of the Southwest, including California, Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, as well as in Georgia and North Carolina according to the Department of Agriculture.

Kids in poverty face six times the number of adverse life experiences — such as economic hardship, neighborhood violence and the death of a parent — as non-poor kids, according to a recent report from America’s Promise Alliance, a network of organizations working to create conditions in which all youth can be successful.

Stephanie Steffano-Davis is principal and student services coordinator of Casterlin Elementary School, which serves two small communities in a mountainous, remote area of South Humboldt County, California. All 34 students in the Title I K-8 school are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

Twenty-three of those students attend the after-school program, where they use the internet to do their homework, since many don’t have the internet a home. Cell phone reception and internet connection are problematic in the area, Casterlin said.

The after-school program emphasizes computer skills, which are important job skills for the students in the future, Casterlin said. The program also provides supper. Despite the poverty, Casterlin points to the advantages of living there — an area with an abundance of hunting and fishing, and unpolluted air and water, she said.

Bridging the ‘expectation gap’

Kids suffer from an “expectation gap,” said Michael Tierney, founder and executive director of Step by Step, a nonprofit that works with kids in the coalfields area of West Virginia. “How do you help kids to dream?”

“Our hope is that by having art, music and “messy science,” they will develop some passion for learning,” said Tierney, whose work “has been very focused on addressing the opportunity gap since 1995.”

Step by Step provides after-school and summer programs for kids through the eighth grade and a leadership program for high school students. The organization reaches about 400 kids during the school year and 200 in the summer.

“We get kids excited and confident about learning and exposed to as many possible futures as possible,” Tierney said. “We take the same kids year-in and year-out and support them.”

Fewer than 5 percent of adults in the area have finished high school, and 49 percent of families are in poverty, he said.

“We hope that their confidence in learning becomes a transferable skill,” he said.

Step by Step creates an opportunity for kids to be nurtured from “cradle to adulthood,” he said, in a broad effort that engages families and focuses on community building.

Through a partnership with the nonprofit Grow Appalachia, the organization promotes family and community gardens and locally grown food. And it offers a peer mentoring and anti-bullying program.

Conditions in the area have changed during the past two decades, Tierney said.

“It is harder and harder to make ends meet,” he said.

The opioid epidemic has taken a heavy toll. He estimates that 40 percent of the children in the Step by Step after-school program live with people other than their biological parents because their parents are addicted, in jail or dead.

In what Tierney calls the “Wal-martization” of America, he said there are fewer high-wage jobs for people with limited education, and parents are juggling multiple part-time jobs with no benefits.

“People are less likely to be home,” he said.

He also said local people used to grow gardens and be more self-sufficient. “People just don’t have the time they used to,” he said.

And, he said, there are fewer summer jobs for youth.

“There’s been a real decline in investment in youth job training,” he said.

Even when kids develop skills and dreams, “they’re still stuck with limited opportunity when they get out of high school,” he said.

Programs that provide young adults with job skills and jobs could directly reduce the opportunity gap, he said.

For example, the Coalfield Development Corporation in West Virginia, which is partnering with Step by Step, offers an on-the-job training and mentorship program that helps young people gain jobs, skills and education.

About 13.4 million children under the age of 18 live in the rural areas of the nation, according to the U.S. Census.

While some are affluent, others live in areas of persistent and deepening poverty. Without efforts on their behalf, these kids will grow up in a separate and unequal America, lacking the opportunities that more affluent youth take for granted.

Rural after-school programs face their own set of challenges

Fourth- and fifth-graders in High Desert Leapin’ Lizards after-school program at Theodore H. Faller Elementary School build Lego windmills and wind turbines as part of a unit on wind and weather. The program operates in Kern County, where one-third of children live below the poverty level.

As rural after-school programs address the needs of kids, they may have to solve problems not found elsewhere.

“There’s a series of challenges not found in urban programs,” said Jeff Davis, executive director of the California AfterSchool Network.

When recruiting staff, the pool of potential recruits is smaller. Staff members may have to wear several hats: A school superintendent may also serve both a principal and a bus driver, Davis said.

Community resources are thinner. There may not be a YMCA or a Boys & Girls Club to partner with, he said. And fewer potential funders exist.

When funding is on a per-student, per-day basis, there may not be enough students to support even one staff person for an after-school program,

he said.

Transportation is another issue. “A bus may leave at the end of the school day, but not for the after school program,” Davis said.

Parents drive long distances just to get children to school, he said. “Vast distances between these places prevent students from accessing programs when they exist.”

Geography and weather impact rural after-school programs more than programs in other areas, he said. An area may have heavy snows and roads may be poor or washed out in heavy rain, he said.

In the past, leaders of rural programs in California felt they couldn’t compete with big urban programs for state funding, he said. Some didn’t even apply for funds they were eligible for, he said.

In two rural summits in 2009 and 2011, the California Afterschool Network addressed some of these issues. As a result, several policy changes were made at the state level in California. A minimum grant for small, rural after-school programs was instituted, important to programs with a small number of students when funding is on a per-student basis. In addition, money is set aside for transportation in rural areas so that after-school programs can bus their students, a crucial ingredient in making programs accessible to students.

California has a total of 4,485 publicly funded after-school programs, according to the Network, and the vast majority (86 percent) only have state (not federal) funding.

RESOURCES

“America After 3 PM: The Growing Importance of Afterschool in Rural Communities,” an Afterschool Alliance report.

“California Rural After School Summit: A Summary of the Recommendations and Implications,” a California AfterSchool Network report.