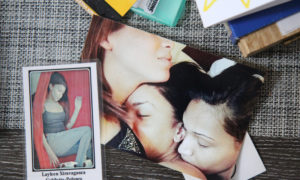

NEW YORK — Every day an estimated 1,500 family members and friends of those incarcerated on New York’s Rikers Island visit their loved ones. The only way on and off the island for visitors is to take the Q100 bus across the bridge. For several months, Queen-based photographer Salvador Espinoza rode the bus back and forth, documenting the stories of the people, mostly women and children, who visit the more than 10,000 people who are detained each day at the jail. He recently exhibited his photography, called Q100, at the QNS Collective in Queens. Espinoza spoke with JJIE and Youth Today about his experience and his photography.

Was it hard to get people to talk to you, to trust you with their stories?

No, they liked to talk, they’re eager to have their story told. And it also takes their mind off everything that they’re thinking of and going through. A lot of them are taking two-hour trips or three-hour trips and then waiting for another three or four hours just to get in. They just want to get their mind off it and it helps for them to be able to get it all out. They like to know that people are interested. I would never ask them what the inmate’s in there for, it was really all about them.

Salvador Espinoza

.

What happened when you got to the island at the end of the ride?

When I first started doing this, I was able to get off the bus and walk around, then they’d take you to the center. What I would do is I would go through the first check-in, and what they do is they have a dog sniff and everyone lines up and after the dog sniff, they check your clothes. So if you have holes on your jeans or if you’re wearing the wrong color, they send you right back on the bus. If you’re wearing too many earrings or whatever the case, if they just don’t like the way you look, they send you right back on the bus. And then there’s further searches once visitors get past the first center.

Later on, the COs [commanding officers] would file onto the bus and say, “If you have anything, you can just leave anything on the bus, it’s an amnesty period.” Then they close the doors in the back of the bus and they file everyone out. That’s something you don’t see on any other bus. I’ve seen people surprised at how strict it was. Even though a lot has come out recently about visits, I think people would be surprised to see how visitors are treated — it’s almost as if you are a criminal. But people are going there with a baby and they’re treated … they’re treated like shit.

Later on, the COs [commanding officers] would file onto the bus and say, “If you have anything, you can just leave anything on the bus, it’s an amnesty period.” Then they close the doors in the back of the bus and they file everyone out. That’s something you don’t see on any other bus. I’ve seen people surprised at how strict it was. Even though a lot has come out recently about visits, I think people would be surprised to see how visitors are treated — it’s almost as if you are a criminal. But people are going there with a baby and they’re treated … they’re treated like shit.

Did you see teenagers or older kids going for visits?

I’ve seen them go visit their friends, I’ve seen whole groups of them go together and get put right back on the bus because they had holes in their jeans or the wrong color or they just didn’t want them there. Some of the kids go by themselves to go visit either parents or friends. I’ve seen 16 or 17 years old allowed at least through the first check-in.

What did you find most interesting?

What interested me the most was just how the conversation around mass incarceration never involves the people on the outside, the effect that it has and how it radiates through the community. You see young kids going through that system — as young as almost newborns I’ve seen — and having to go through the searches and the detectors and they see their parents go through it and it has this effect on their psyche and it rattles throughout the community. So they’re already indoctrinated into the system and it kind of seems normal — if these kids get locked up later on, it seems like just a normal kind of step for them, they’re used to getting searched, they’re used to getting detained.

Salvador Espinoza

.

What would you like to see as a result of your work?

I really just want people to be aware that no matter what is going on with the inmate — and in some cases it might be something that they did that was pretty hard, or in other cases maybe not. But either way, it still has an extreme effect on the family. That’s what I want people to take away from this. And unfortunately, mass incarceration makes it so there’s 10,000 people there on any given day, so you picture the city — 10,000 people are taken away from their families, taken away from their kids, just to keep a profit or to keep the system intact. It’s something we can’t sustain because it’s just this revolving door — you’re breeding kids from a young age to go into the system. I just want people to be more aware of this.

What made you want to ride the bus?

There were different layers to it. One was because I grew up in the neighborhood, I would always see the bus. I’d see inmates getting off late at night — they used to let inmates off around 3 in the morning or so, which they’ve kind of stopped since the neighborhood’s changed. I was shooting another project at 7 or 8 in the morning and I’d just see lines of people getting on. So I said, ‘Let me get on that bus and see what it’s like for people.’ So I rode that for a while without shooting anything, and after a couple of weeks I decided I should shoot and get people’s stories.

What are you working on next?

Salvador Espinoza

I’m doing more research about what happens to people when they get out, when they leave and how they are left with pretty much a Metro [publictransit] card and the bag with whatever they came with. It kind of invites them back in a way, almost like the system expects them to come back. I think one of the things is to see what kind of help people get once they’re out — to see what help they get mental healthwise or just day-to-day help getting jobs and reintegrating back into society. I think taking these rides has made me think about that more — I think we should all think about that too, because they’re all kind of just left out there. And I’m going to start riding the bus again in February. I’m going to start shooting again and see where it goes from there.