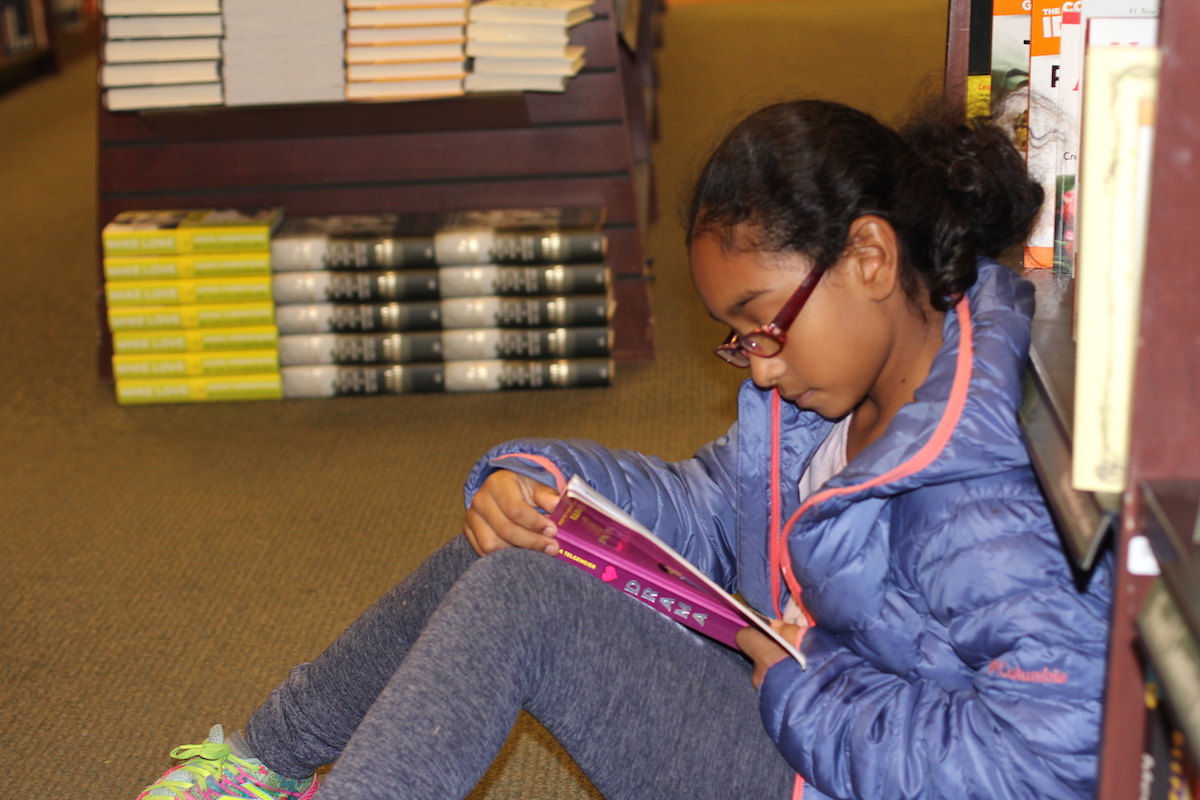

Photo by Annie Nova

A young girl reads in the final days of the Bronx’s last general-interest bookstore.

NEW YORK — Every few weeks, Carmen Donis, 44, travels for an hour on subways and buses each way to the Bronx’s only bookstore from her apartment in the Castle Hill neighborhood. She homeschools her 12-year-old daughter, who has autism, and says she needs to look through the books to know if they’ll grab her daughter’s attention, something she can’t do online.

But at the end of the year, Barnes & Noble will close, leaving a borough of more than 1.4 million people without a general-interest bookstore.

“When she reads, she expresses herself well,” Donis said, walking through the education section of the local store. To gear up for life in a bookstore desert, she orders a one-year supply of books to use in teaching her daughter this school year.

But then what?

“I don’t know what I’m going to do,” she said.

That the Barnes & Noble in the Baychester neighborhood of the Bronx will close at the end of 2016 is distressing to many residents. The loss of the expansive children’s section is particularly painful to the store’s youngest customers, their parents and others who remember this place as their first introduction to worlds beyond the Bronx.

“I grew up here,” said Alycia Rawlins, 15, sitting on the carpet of the children’s section with her arms crossed. “It hurts.”

Rawlins said she’d come here on the weekends with her mother who would make her pick out a book and read it. She became addicted to the children’s horror series Goosebumps.

“I loved the feeling of being scared,” she said. “I read Stephen King now.”

Seventy-five percent of children’s books are still bought in stores, said Susan Neuman, a professor of literacy development at New York University.

“In poorer neighborhoods, those Barnes & Nobles are a centerpiece. Children begin to understand that reading is a very important part of life by seeing other people reading,” she said.

But that appreciation for words might not occur in environments where books and reading are missing, Neuman said.

“[Some young people] don’t understand the necessity of reading because they don’t see anyone in the community doing this. By the time they’re teens, they’re totally turned off to reading. They don’t see the purpose,” Neuman said.

And a lack of bookstores in a neighborhood can be especially dangerous during the summer months, she said.

“The summer slide is very, very serious. Children during the summer don’t have any resources, and so the achievement they’ve done slides during the summer.”

Joseph Daka, 11, pulled out a book he’s read many times before. It’s about the Nazi invasion during World War II. He said he reads historical fiction “to see how the characters confront disaster.”

“It taught me how the kids survived,” he said. “Why do I have to travel to Manhattan for a Barnes & Noble?”

Barnes & Noble is losing locations across America. In 2008, there were 726 stores; by 2015, they were down to 648 sites. But Manhattan still holds six of the chains and approximately 70 independent bookstores, according to Reference USA, a business research database.

“I’m sad. But it’s not forever,” Chloe Corneal, 9, said, sitting next to the Dr. Seuss books. “People in the Bronx still need to read.”

But her grandmother is less assured.

“Where are we going to go with our children now?” Lourdes Mendoza asked. “We used to sit here for hours, with her crawling around. She started reading at [age] 4. We live here.”

Jessica Cruz, 26, began a petition to fight the closing of the Bronx’s Barnes & Noble. More than 3,000 people signed it.

“There was a sense of wonder, all of these greats books in one place,” Cruz said. The memoir, “The Moveable Feast,” changed the way she thought about her future.

“It makes you feel like ‘Wow, if Earnest Hemmingway can get up and move thousands of miles away to Paris from Oak Park, Illinois, and win a Nobel Prize in literature, then Bronxites can make our dreams come true here.”

Amelia Zaino, 26, was 9 when the bookstore opened in her neighborhood. She says it was “a big deal.”

“I was always a shy kid so I didn’t really hang out,” Zaino said. “A lot of times I felt lonely, and I just wanted to get a book.”

Those days spent alone in the bookstore, reading Japanese comics called manga, would later help her to make friends. “In high school, it was a great way to bond with people. We might be from different countries, different neighborhoods, but we all liked manga,” she said.

“There’s this misconception that Bronxites don’t read,” Zaino said. “If we don’t read why do I have to wait on a line every time I come in here?”

“It’s a surprise to everyone,” the Bronx Barnes & Noble store manager John Beola said. “We did well.”

But the property landlord seems to have found himself in a different plot.

“Barnes & Noble wasn’t making money. They were struggling,” said Jerry Welkis, who represents the property owner of the store. The department store Saks Off 5th signed a 10-year-lease in August. “Saks was very interested, and we felt we couldn’t pass up the opportunity.”

In the meantime, the demand for books in the Bronx is only growing. Between 2002 and 2014 the number of books checked out from libraries in the borough increased by 35 percent — the largest jump of any borough, according to the Center for an Urban Future.

But residents say libraries won’t fill the hole that Barnes & Noble will leave behind. The bookstore stays open until 10pm, while most public libraries close between five and seven. The 25,000 square-foot bookstore offers a wider selection of reading materials and there’s no pressure to keep their children quiet, residents say. Plus, books from libraries need to be returned.

Anjali Bromfield, 20, sat in the back of the children’s section at a small table, flipping through “Where the Wild Things Are” and “The Tale of Peter Rabbit” in search of inspiration. She plans to write a children’s book.

“I have this idea of a tree that’s the center of the neighborhood and if it gets torn down everything is destroyed. The whole city changes,” she said. “It’s ironic — now this is being torn down.”

“My grandmother recently passed away. She was always about reading so I think of her in here,” Bromfield said, tearing up. “It’s the end of an era.”