Jessica Chandler spent her teenage years in foster care in California after her parents divorced and her mother struggled with mental illness. At age 18 she became pregnant. She was terrified, she wrote in an op-ed piece in the Los Angeles Times in May 2013.

Luckily, she found assistance with health care, education and legal matters through the Alliance for Children’s Rights and other groups.

Chandler’s younger sister, who also got pregnant, was not so fortunate; she had little assistance and her child was eventually removed by child protective services and put in foster care.

Teens who have been foster kids become pregnant at a far higher rate than teens not in the child welfare system, said Kim Nolte, president and CEO of GCAPP, the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Power & Potential. GCAPP is a Georgia nonprofit that has worked in the area of pregnancy prevention for 18 years.

The most recent estimates of pregnancy among foster teens come from the continuing California Youth Transitions to Adulthood study, in which more than 700 youth were surveyed. A just-released followup of the study showed that by age 19, nearly half of the young women in foster care had become pregnant and one-fourth had given birth.

Recent figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show a dramatic drop in the teenage birth rate. However, “there are no national data that I am aware of” showing birth-rate trends over time among foster kids, said Mark Courtney, professor at the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration, said in an email.

The CDC report showed that although the birth rate among Hispanic and black teens has been cut in half since 2006, it’s still twice as high as that of white teens.

It is unlikely that the big disparity between foster kids and non-foster kids has changed.

Among the problems are the fact that teen mothers are more likely to lose their own children to foster care, perpetuating the cycle.

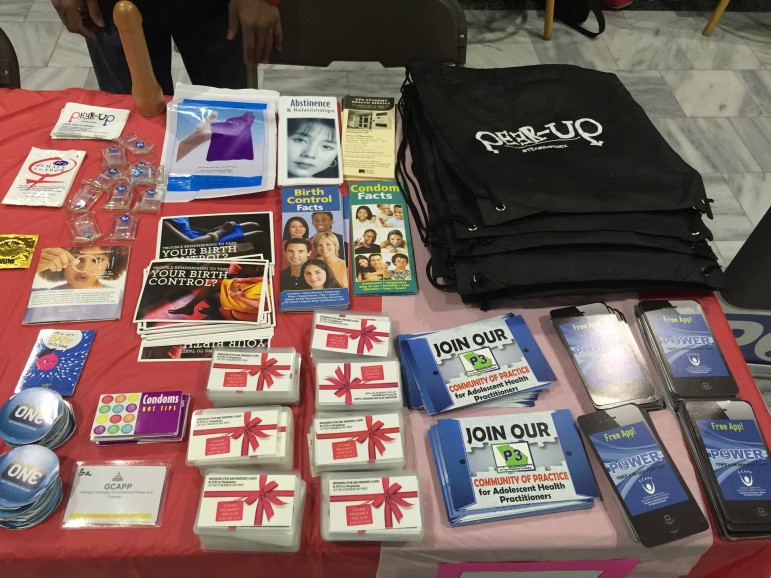

GCAPP

Lack of good information about sex, relationships and contraception is one of the reasons teens who have been in foster care have a higher rate of pregnancy than teens in general.

Why the high rate among foster kids?

Foster kids have a high teenage pregnancy rate for several reasons, Nolte said.

Sexual and physical abuse are major risk factors, she said. Kids who are abused learn they don’t have the right to say no, she said. They haven’t learned appropriate boundaries. They may have developed coping mechanisms that are unhealthy, she said.

Because their family has broken up they crave the love of family, she said.

“For some of them, having a baby [seems to be] the best thing that has happened in this life,” Nolte said.

In addition, parenthood at a young age seems normal, she said.

Kids who go into the child welfare system have often been in an environment of poverty, and they may see many people having children at a young age and not pursuing further education, Nolte said. Foster kids don’t see that it would make any difference if they waited until they are older to have children, she said.

In her Los Angeles Times article, Chandler wrote about the lack of information available to foster kids.

“A lot of the teen moms I know who grew up in the foster care system had no adult who talked to them about puberty, much less about how to prevent pregnancy,” she wrote. “When they became pregnant, many hoped their children would become the families they never had, but it’s rarely that simple.”

But young people in foster care want to have conversations about love, sex and relationships, Nolte said.

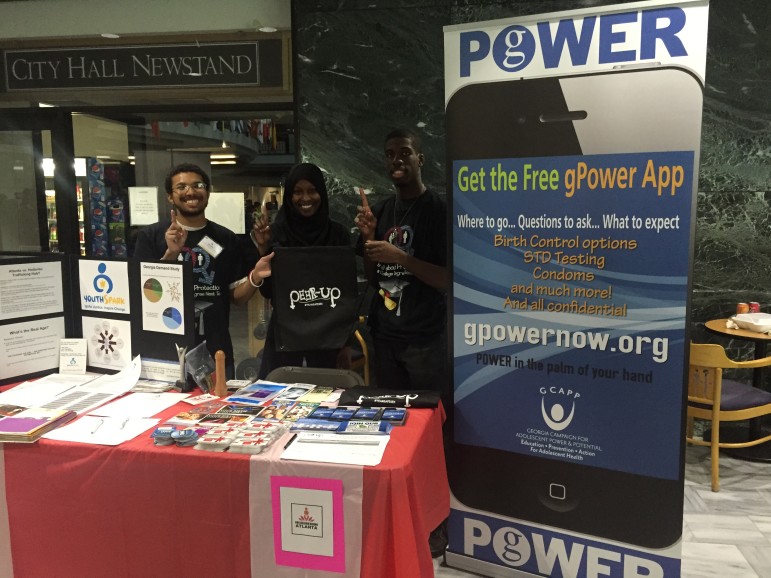

GCAPP

Young women who have been in foster care tend to miss sex education classes in school because they move from foster family to foster family, according to the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Power & Potential.

Her organization, G-CAPP, surveyed foster kids in 2010 in conjunction with the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy.

Teens said they wanted to have discussions about sex and love with their birth parents, and secondly with foster parents, but only if they had a good relationship with foster parents.

Teens wanted pregnancy addressed as something that could happen to any teen, the report said. They didn’t want to be singled out or labeled, but they wanted medically accurate and reliable information.

“Young people in care want this information,” Nolte said. “They have tons and tons of questions,” she said.

But “youth in care fall through the cracks from moving around,” she said. They may move from foster family to foster family, and from school to school. They miss sex education classes in school, she said.

“We need to focus on making sure they’re getting the care they need” and focus on helping foster parents develop trusting relationships with them, Nolte said.

The goal is to develop a system so that foster parents, caseworkers, teachers, school nurses and others are able to have conversations with foster kids that reinforce the same message of delaying pregnancy, she said.

Miranda Sheffield, now 30, grew up in foster care and became a mother at 18. Today she works as a peer advocate in the Children’s Law Center in Los Angeles talking to foster youth about reproductive health and legal rights.

“There’s a lot of missed opportunity to educate youth” not only about health and birth control but about being responsible and having sex, she said.

“Pregnancy rates would not be so high if there were more opportunity for education about how things work,” Sheffield said.

One model for pregnancy prevention

GCAPP is an example of a program providing education and support to foster kids around the issue of pregnancy.

GCAPP

A phone app known as gPower has been developed by the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Power & Potential to provide information about health, birth control and available clinics.

It pushes for evidence-based programs in schools and community-based organizations to reduce teen pregnancy. It also trains foster parents and caseworkers to have conversations with youth reinforcing delaying pregnancy.

GCAPP developed a phone app known as gPower that provides contraceptive information, helps girls become their own health advocate, links them to about 300 clinics in Georgia and gives them a way to rate those clinics.

The organization also provides training (about talking to kids to reinforce delaying pregnancy) for the insurance company that handles medical care for kids in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems in Georgia. And it operates five Second Chance homes for teen moms and their babies. These homes serve 40 to 50 young women each year, Nolte said.

The organization also has a focus on preventing second pregnancies, she said.

Foster kids face many challenges. “It’s no fault of [foster kids] that their families fall apart,” Nolte said. We have to find out how to support them, she said.