WASHINGTON — Children’s advocates say it is essential to increase the number of willing foster families as some states move away from using group homes.

Better recruitment and retention techniques could help ensure more placements are available, whether they are with foster families or relatives, said advocates from across the country during a Capitol Hill briefing held Wednesday by the Senate Caucus on Foster Youth, the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute and Fostering Media Connections.

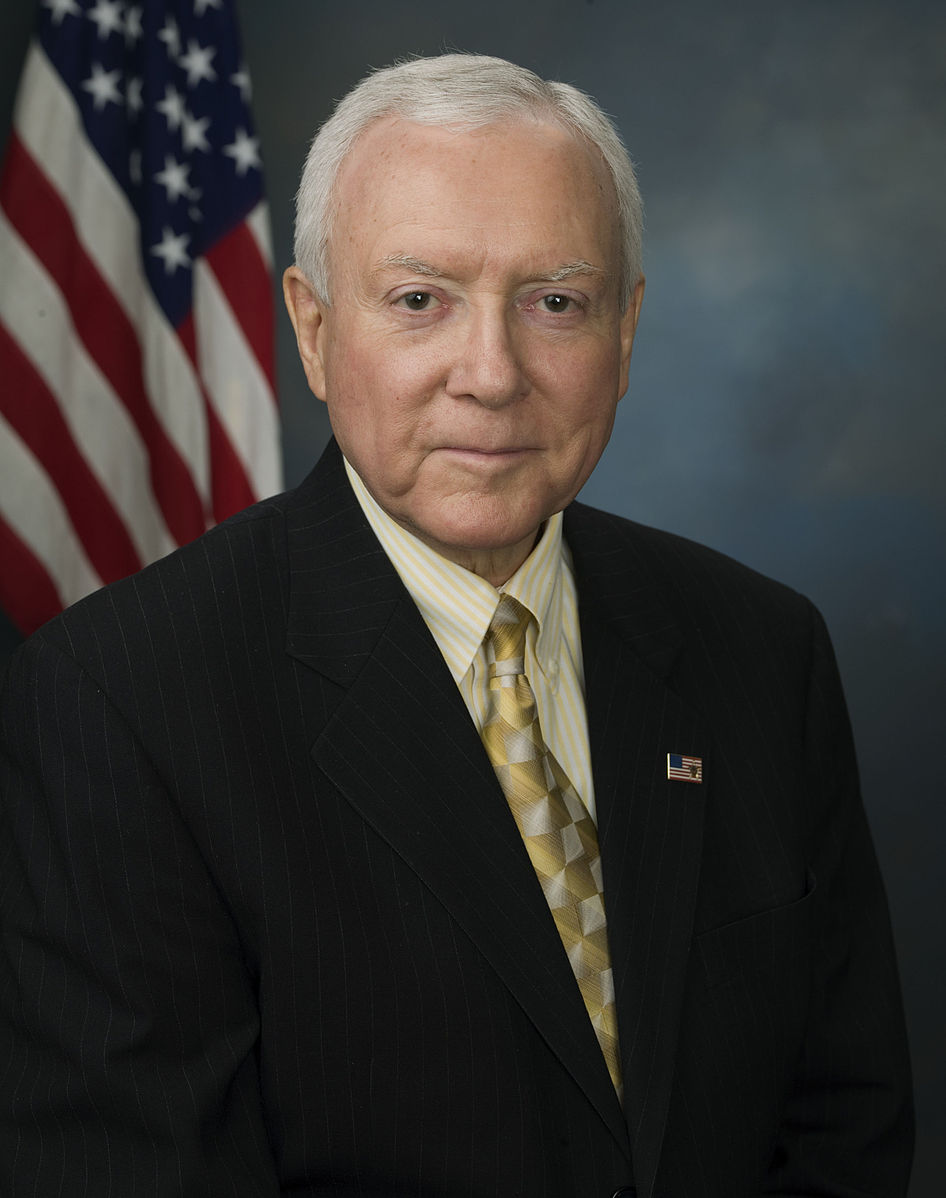

Sen. Orrin Hatch

Lawmakers at both the federal and state level want to reduce the use of group homes because of the benefits for children of living with a family and the risks of abuse at group homes. Senate Finance Chairman Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, has been an outspoken critic of group homes and wants to curtail their use. In California, a new law aims to drastically scale back the use of group homes.

Arnie Eby, chair of the National Foster Parent Association, said the rewards of fostering children are great, but the field should pay more attention to alleviating the risks for potential foster families.

Foster families have to counter negative public perceptions about the child welfare system, navigate how fostering will affect their existing families and consider how they will deal with the needs of a child who has experienced trauma, Eby said.

He recommended improving mentoring programs that pair seasoned foster parents with new participants or with biological parents, promoting opportunities for respite that involve the whole family and increasing funding for day care.

“It’s not easy to find money to do that, but in the long term I think it provides an incredible opportunity for additional families to be involved,” Eby said.

The speakers at the briefing emphasized the importance of kinship care as one way to increase the number of homes open to children. In 2014, 29 percent of children in the foster care system were living with relatives.

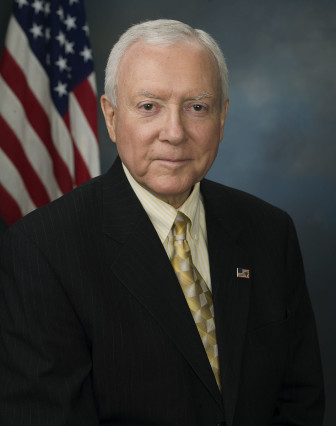

Sharon McDaniel

Policymakers and practitioners can support families by looking for ways to build up their strengths rather than dismiss their potential as foster parents, said Sharon McDaniel, founder and CEO of A Second Chance, a Pennsylvania nonprofit that supports kinship caregivers. Groups can look for ways to help potential foster parents find appropriate housing or meet other licensing requirements, she said.

“We have to also not look at families through this pathological lens of ‘They need to be fixed,’” she said. “They are having moments; they are having crises, just like we all have in our own families. I think if we move to that framework and that lens, we will find more families than we do.”

That support is critical for families as they foster children but also after they adopt or become permanent guardians because problems may come up for years after a placement, especially among children who have experienced trauma, McDaniel said.

“We have to think about post-permanency as not just 15 months after a young person leaves, but as life-term,” she said.

The briefing also looked at the role religious organizations can play in recruiting and supporting foster families.

Elizabeth Wiebe

Elizabeth Wiebe, vice president for engagement at the Christian Alliance for Orphans, said many churches have established formal ministries for foster families, or have informal networks that fill the same role. Congregations can help bring meals, mow lawns or convene support groups for foster families.

Nationally, churches are choosing to emphasize the need for foster families in their county or ZIP codes rather than more overwhelming national numbers. The smaller scale makes the work seem more manageable, Wiebe said.

“The churches are realizing, ‘This is something we can do. We can make a difference,’” she said.