Photo courtesy of Oregon Ask

Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon visits a branch of the SL3 summer learning program. SL3 stands for learning, libraries and lunches to keep kids engaged during the summer.

The students gathered at Nellie Muir Elementary School in Woodburn, Oregon, had a lot of questions for Sen. Ron Wyden when he visited them a few years ago.

Just how many bathrooms does the White House have, they wanted to know. And by the way, they asked, was President Obama his brother? They were excited and engaged, eager to demonstrate their knowledge and learn more. They were “just kids being kids,” said Karen Armstrong, the after-school program coordinator for the Woodburn School District.

But the children from across the district weren’t there for a regular school day. Instead, they were spending their summers in the school library, as part of a program called SL3 that emphasizes the power of learning, libraries and lunches to keep kids engaged during the summer.

Participating programs keep school libraries open, which are often easier for students to get to than regional public libraries, especially in rural communities. They offer meals, and partner with community organizations to provide enrichment activities. When the program began four years ago, four sites participated. In 2015, the number had grown to more than 30.

Wyden has not been the only visitor. The program also has drawn notice from other policymakers in the state, a group of whom began 2016 looking for ways to create a permanent summer learning council that would find ways to ensure every child has access to summer programming.

“It’s really brought attention to the reality that lowincome kids don’t often have a place to go or things to do in the summer,” said Beth Unverzagt, director of OregonASK, which coordinates the program, which began with a small grant from the National Summer Learning Association.

A nationwide movement

Across the country, communities are looking for creative ways to expand summer programing — and gaining policymakers’ support as they do. They’re making use of school libraries and public libraries, community centers owned by public-housing authorities, and even barber shops and city buses.

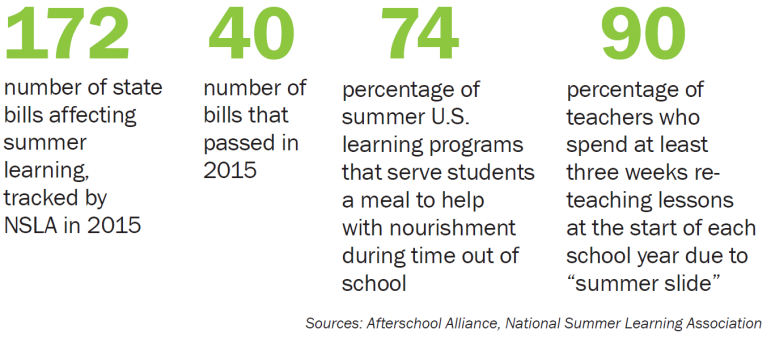

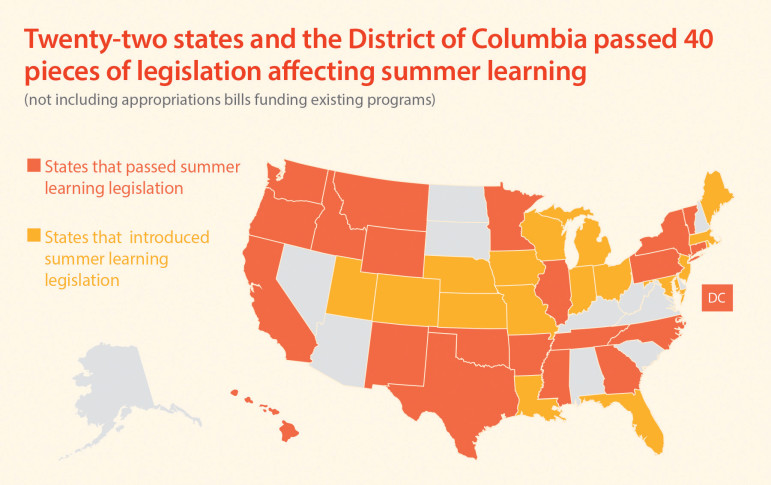

In 2015, the National Summer Learning Association (NSLA) tracked 172 state bills that affect summer learning, and lawmakers in 22 states and the District of Columbia passed 40 of them. The legislation includes bills that increase funding for particular grant programs but also those that create new literacy opportunities, encourage STEM, create out-of-schooltime advisory groups and celebrate summer learning with proclamations and resolutions.

A steady drumbeat from advocates explaining the risks of summer learning loss has helped draw states’ attention to the need for summer programming, said Sarah Pitcock, chief executive officer of the National Summer Learning Association. During the summer, low-income youth lose two to three months of reading achievement, but their higher-income peers make slight gains, widening the achievement gap, say researchers.

Summer programming also has picked up additional momentum as states work to ensure students meet critical reading goals by the end of third grade. A stretch of months that used to look like downtime now is an opportunity.

“If you need more time for learning, if you can’t cram it into 180 days, then the logical place to go is summer,” Pitcock said.

But there’s more than one way to develop a summer program, when it comes to place, price and partners, said Pitcock. Every community will need to find its own way to make summer learning a reality, whether they’re thinking about literacy, job training, the arts, STEM or any subject in between.

“Our goal is to break down the perception that learning has to happen in a place with four walls and a teacher and during certain hours,” she said.

Policy provisions

In some cases, policymakers have supported the heightened interest in summer learning with new funding.

Rachel Gwaltney, director of policy and partnerships at NSLA, said the preservation of the 21st Century Community Learning Centers initiative in the Every Student Succeeds Act is one powerful sign that policymakers are paying attention to the out-of-school time. The initiative is the only federal funding source dedicated solely to after-school, before-school and summer learning programs.

Local jurisdictions also are finding ways to support summer programming, such as the creation of dedicated funding streams for summer learning in San Francisco and Seattle, she said.

But, there is still a long way to go to meet the gap between the demand for summer learning programs and their availability. Cities and school districts often think of summer funding as “extra,” the first thing to get chopped when budgets are tight, and separate from education planning for the other nine months of the year, said Gwaltney.

“A lot of places have that mindset. That’s the mindset that we’re continuing to try to change,” she said.

National Summer Learning Association

.

Crucial, collaborative planning

The trend toward careful, early planning for summer programming is an encouraging one, said Ellie Mitchell, director of the Maryland Out of School Time Network (MOST).

“For me the big summer story is the systems building and how important it is. Being part of a collaborative is critical,” she said.

A network of organizations, including MOST and The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation, came together in Baltimore to create SummerREADS, a drop-in program designed for kindergarten through third graders that takes place in public school libraries. Students receive books, are eligible for summer meals and participate in hands-on lessons in STEM, the arts and the environment.

Mitchell said strong partnerships have been key to the program’s success by bringing together government, nonprofits and philanthropic organizations. In turn, those organizations have been able to think beyond SummerREADS to other ways to promote summer learning across the city.

“Baltimore’s just gotten to the place where everyone is thinking about summer earlier and in a much more coordinated way,” she said.

In early data collection, SummerREADS already has posted impressive results. At nine sites in the summer of 2015, 525 students participated at some point during 1,080 open library hours.

Nearly all parents surveyed said the program has been an academic boost to their child. And, 75 percent of participants who took a widely-used literacy assessment before and after the 2015 program maintained or gained reading proficiency during the summer.

Sheryl Goldstein, managing director of programs and grants at the Weinberg Foundation, said the presence of welltrained library staff who understand families’ needs has been a boon to the program.

And, critically, the children and families who participate in SummerREADS are eager to make the most of the program, she said. The desire to participate in summer programming is there; communities just have to find the right ways to meet that demand.

Resources:

- National Summer Learning Association (summerlearning.org) is a one-stop shop for the latest summer learning research and policy trends.

- Afterschool Alliance (afterschoolalliance.org) has resources about how the federal Every Student Succeeds Act will affect summer learning programs.

- Food Research and Action Center (frac.org) offers resources for organizations that want to incorporate summer meals into their programs.