Photo courtesy of engaging schools

Engaging Schools’ participants work with an adult on principles of youth development and conflict resolution in order to become peer mentors for one another. Learning to respond to conflict and bullying is a key part of the peer mentor program.

In November, videos made their way around the Internet of two violent incidents in U.S. classrooms. One was a sheriff’s deputy in South Carolina flipping a high school student to the floor while she sat in her chair. The officer dragged her after she resisted handing over her phone.

The other video was from a Georgia middle school of a student raining punches on the back of the head of another student who was sitting down.

Mayhem and violence in the two incidents dominate the screen, but what is also striking is the reaction of other students nearby — or lack thereof. One covers her eyes. One recoils in his seat and doesn’t move at all. They have a reason to cower or freeze. A spokesperson for DeKalb County Schools in Georgia said in an email that authorities deemed the incident serious enough to warrant a criminal investigation.

So, what about the young people who are bystanders to violence? Are they just left to deal with their own emotions? Several of these bystanders gaze straight ahead, still, and do not react.

So, what about the young people who are bystanders to violence? Are they just left to deal with their own emotions? Several of these bystanders gaze straight ahead, still, and do not react.

“People talk a lot about young people who have witnessed violence, whether it is in the classroom, or the home, or other settings, and it does have a significant impact on children, it can stay with them,” said Larry Dieringer, the executive director of Engaging Schools in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “And I’m not surprised by the reaction to try and stay out of the limelight.”

The nonprofit Engaging Schools works with districts and individual schools, supporting teachers and leaders to improve school climate and culture, and increase student engagement. Engaging Schools has a program called Resolving Conflict Creatively and Adventures in Peacemaking for earlychildhood, elementary and after-school providers.

What concerns Dieringer was the reaction, or lack thereof, of the two other adults present in the South Carolina incident. If adults do not act to stop an incident, children can lose trust in the school as a safe place, he said. It can be an unintended consequence for the young people who witness incidents and have done nothing wrong.

“I don’t think the kids could have done much in that case, but the adults could have,” Dieringer said. “I would have hoped one of the adults would have tried to stop it. When there is a traumatic incident, it is important for the adults to step forward, because it is the adults who shape the culture.

“There were two other two adults in the room, not just the officer. One was an assistant principal and the other was the teacher. I was disturbed that they chose to bring in an officer to deal with a fairly standard disciplinary issue. Bringing in an officer suggests the behavior was criminal. It was not.”

Witnessing violence, ripple effect

School administrators and teachers should not assume that just because other students in the room said nothing, or did nothing, there is not some lasting impact, according to a study by the Centers for Disease Control in 2015 called “Understanding School Violence.”

From the report: “Not all injuries are visible. Exposure to youth violence and school violence can lead to a wide array of negative health behaviors and outcomes, including alcohol and drug use and suicide.

Depression, anxiety, and many other psychological problems, including fear, can result from school violence.”

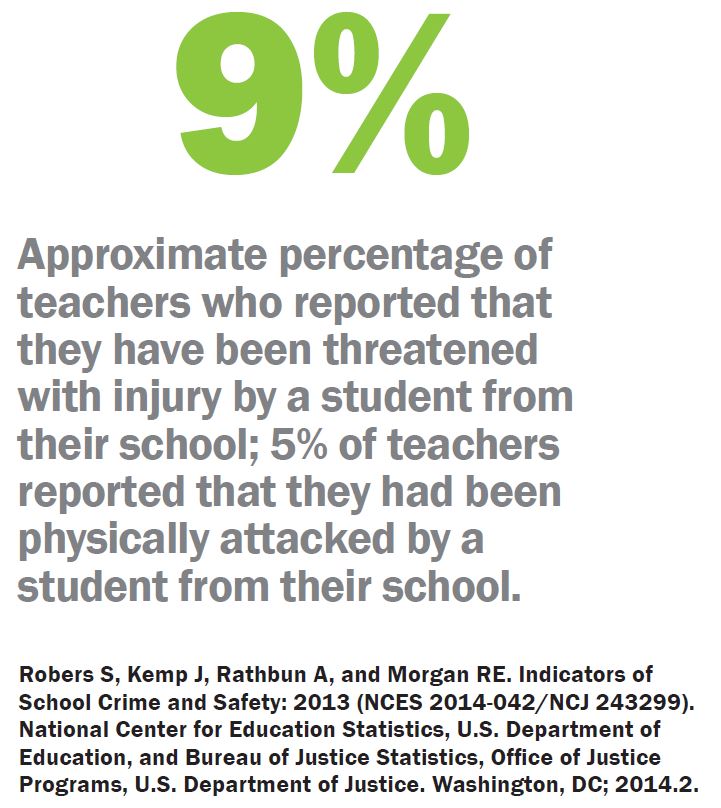

The CDC’s most recent comprehensive study of school violence in 2013 of youth in grades nine through 12 found 8.1 percent reported being in a physical fight on school property and 7.1 percent reported that they did not go to school on one or more days before the survey because they felt unsafe at school.

It seems fairly obvious: There is psychological impact of violence in schools. Yet still some schools fail to create a pathway to normalcy for youth who witness violence.

“We know trauma can have an impact on learning and behavior at school,” said Susan Cole, a lecturer in the Harvard Law School and the director of the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative, which is a collaboration of Massachusetts Advocates for Children and Harvard Law School.

Trauma-sensitive schools

“You have to look at the person who is acting out and the ‘freeze’ response of the other students,” Cole said. “We really need to stop and create what we call a Trauma Sensitive School. Everyone would understand how to respond to these incidents. You want the kids not to be all curled up.”

A trauma-sensitive school is not a curriculum, but a culture and a way of thinking, Cole said. It has to be a whole-school endeavor — from the lunchroom, to the bus, to the hallways, to the classroom — and the mantra must be: “We’re trauma sensitive because it is what we do here.”

Cole said a policy for trauma-sensitive school is not some state-mandated, far-flung plan. It is local and includes principals, students, teachers and parents. If the principal of a school, the CEO, does not buy into the idea of a trauma-sensitive school, there is little chance it can succeed, said Cole.

Cole said Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is working on developing a Trauma Sensitive School Certificate.

“You need a teacher who is able to have a relationship with the kids and calm them down,” Cole said. “Kids have to be made to feel safe. The only way I can tell you to help those kids [who are afraid] is to have a trauma-sensitive school, where you manage those situations so that they don’t happen in the school. A core is having that relationship so the educator can calm everybody down and make kids feel safe.”

Dieringer said if adults do not handle confrontations properly, students can associate adult figures in their lives with chaos and danger.

“The adults need to communicate back to the student, ‘We’re going to keep this a safe place’,” Dieringer said.

“It’s also a chance to give kids a chance to talk. The key point is to give the students a chance to express what’s on their mind and for adults to listen to them and to reassure them that most, if not all, the adults are working hard to make it a safe place, and we’re going to do our best not to let it happen again.”

“It’s also a chance to give kids a chance to talk. The key point is to give the students a chance to express what’s on their mind and for adults to listen to them and to reassure them that most, if not all, the adults are working hard to make it a safe place, and we’re going to do our best not to let it happen again.”

After-school initiatives are just as valuable as in-school remedies, according to Harvard’s Cole. A game of chess, painting and just running around ease the stress of the school day environment, she said.

“After-school programs have a great opportunity to become trauma-sensitive and can provide a wonderful respite for kids,” Cole said. “Trauma, it is said, is often held in the body, and movement activities—arts, games and play—provide opportunities for students to relax and learn so many important skills that may have been affected by a fear of safety. Afterschools should focus on doing what afterschools often do best.”

The bystander effect

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, between 1992 and 2013, the total victimization rates for students ages 12 through 18 generally declined both at and away from school.

The statistics show anti-bullying efforts are working at some level, but Anne Gregory, Ph.D., associate professor at Rutgers University’s Graduate School of Applied and Professional Psychology, says the focus has to be on reducing “the bystander effect.”

“When peers stand by and cheer on or laugh when a peer is being hurt, then it increases the likelihood that the victimization will continue,” Gregory wrote in an e-mail. “So, bullying interventions now often focus on peers being “upstanders”… learning to intervene (or not reinforce) the negative peer behaviors.”

Students have to learn to demand other students stop videoing confrontations and fights at school with their phones. The videos posted to the Internet ratchet up the ill will in a school, Gregory said.

Gregory also wrote, “Upstanders are taught to say something to discourage, walk away (not to reinforce behavior), tell an adult.”

“I would say confront after the event when people are more emotionally regulated,” Gregory suggested, “and in front of other people, formal complaints/grievances, organize other youth … etc.”

How involved should students become as upstanders? Daniel Losen, director of Center for Civil Rights Remedies at University of California, Los Angeles, said students should absolutely not have intervened with the sheriff ’s deputy in South Carolina. Losen said given the racial histories in some schools, it could have had tragic consequences.

Losen said students need to learn remedies “to deescalate” in ways that empower them.

The confrontations in school that suck innocent bystanders into the cauldron are part of a larger problem. For years, experts have studied the open spigot that is the school-to-prison pipeline. A fight at school leads to an arrest and placement in an alternative school, which leads to more aggression, and then incarceration.

“We have to understand why children are acting up,” Cole said. “So, look at the South Carolina incident. She wouldn’t hand over her cellphone. She was just put in foster care, and she felt the need for control, and it is one of the impacts of trauma. You want to avoid those situations by understanding the role that trauma is playing.”

The trauma of participants is passed on to the bystanders, who are made to feel helpless. They are sitting in class and then suddenly are swept up in drama not of their own making. It can all be unsettling.

“It is about a culture shift and creating a traumasensitive environment where kids feel safe to learn,” Cole said. “It is where everybody feels connected. We can have all the metal detectors in the world, but the core of this is making sure everyone feels connected to the school, not isolated.”