Barbara Cervone, Ed.D, president/co-founder of What Kids Can Do and its nonprofit publishing arm, Next Generation Press.

In San Francisco’s Tenderloin district, everyone has a story to tell. Long home to the city’s homeless and mentally ill, the Tenderloin also pulses with immigrants upended by turmoil in their native country. Here, among the single-occupancy hotels, a family of five can squeeze into two small rooms and make a fresh start. This is the poorest and most densely packed neighborhood in San Francisco. It also has the highest concentration of children under 18 anywhere in the city.

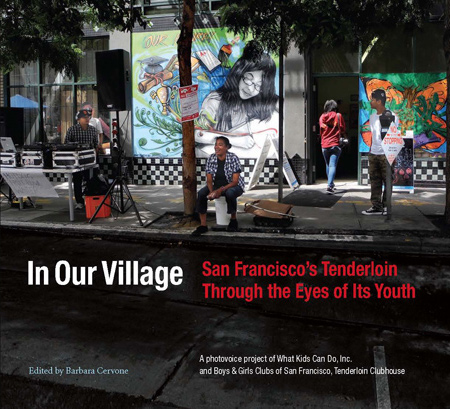

Who better to describe what it’s like growing up in San Francisco’s so-called underbelly than the young people who live there? In a new book, youth from the Tenderloin Clubhouse at Boys & Girls Clubs of San Francisco (BGCSF) do just that, weaving photos and stories to create “In Our Village: San Francisco’s Tenderloin Through the Eyes of Its Youth.”

For me and the small nonprofit I founded in 2001, this is familiar territory. For more than a decade, What Kids Can Do (WKCD) and its publishing arm, Next Generation Press, have joined with young people across the globe to document daily life in the places they call home. Armed with curiosity, digital cameras and voice recorders, youth ages 8 to 19 from North Hollywood to New Orleans, from the jungles of Nepal to a coffee-growing village in Ethiopia — like youth in San Francisco’s Tenderloin — have gathered the stories that mean the most to them.

Serendipity and an unwavering belief in youth vision and voice, not funding, have fueled what we’ve come to call the In Our Global Village program.

Tanzania beginnings

It began in 2005, when my 20-something son was living and working in a remote village in Tanzania, where life depends on the bounty of each year’s harvest. Stunned by my first visit, I invited youth at the village’s secondary school to take on the role of photojournalists and tell their village’s story. I returned a year later, and for two weeks a dozen students and I walked the 40 kilometers of dirt trails that crisscross the village, reporting on topics from maize porridge to livestock to the bareness of the village infirmary. On parting, the students told me they didn’t believe that anyone outside their village would care about their story and their lives.

They were wrong. “In Our Village: Kambi Ya Simba Through the Eyes of Its Youth” has sparked more than 60 other books by young photojournalists in the making.

[Related: California Photographers Focus on Life After Foster Care in New Book]

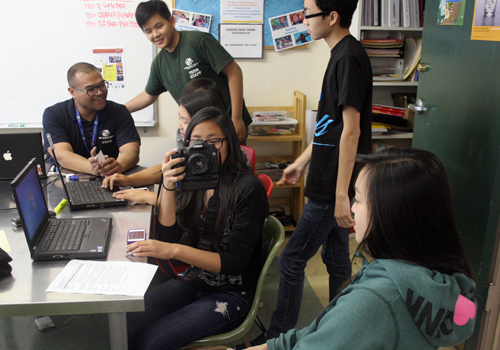

In this instance, a book was not part of the initial plan. When I visited the Tenderloin Clubhouse of the Boys & Girls Clubs of San Francisco in May 2014, I hoped to create a feature story about the organization for our website, WKCD.org. While there, I met Kay Weber, who directs the art programs at the Clubhouse. He was eager to show me the photographs that his students, first- and second-generation immigrants of all ages, had been taking as part of an after-school neighborhood photovoice project.

Our Tenderloin success

As noted earlier, The Tenderloin, while a thriving immigrant community, is best known for being the epicenter of San Francisco’s untouchables: the homeless, the addicted, the mentally ill. These were the subjects that drew our young photographers.

Francelle Mariano

Team members at the Tenderloin Clubhouse

The resulting exhibit, “Ain’t Nothin’ Tender,” turned heads at the San Francisco gallery where it hung. Seventeen-year-old Lucely Chel’s photo of a homeless man embracing his dog while sleeping on the sidewalk is unforgettable. Nineteen-year-old Chris Muzar’s picture of the street mural on the wall outside the Tenderloin Club’s teen center dances with light and shadows.

In less than an hour, Weber and I agreed that I should return to the Tenderloin that summer. Together, with a corps of the Club’s teen leaders and younger students, we would create a book-length photo essay about this extraordinary neighborhood as seen by its youth.

From the start, we agreed the book would show the tender aspects of the Tenderloin, as well as its rough side. The youth thought hard about the photos they took: of each other, their families, kids playing, wall murals and sidewalk art, community celebrations and more. They decided on the chapters and stories they would tell, about: the blessings of growing up in one of the world’s most diverse communities, interdependence, sizing up danger in a neighborhood where violent crime rules, favorite foods, learning to swing a baseball bat, squeezing a family of five into two small rooms.

They talked about fulfilling the dreams that brought their parents to America. “Our success will make their journey and all of their sacrifices right,” said Albert, whose family is from Vietnam. “We carry this knowledge with us every day.”

“No doubt, the young people who have contributed to this volume will move on and out of the Tenderloin,” said the Tenderloin Clubhouse’s director, Esan Looper, who himself grew up in the neighborhood. “This is why their parents came to America: to give their children opportunities they could barely imagine. Wherever they go, though, I bet these young people take with them all they learned growing up in the Tenderloin, lessons they won’t find anywhere else.”

In the months to come, the young authors will share their lives and dreams in venues across the city. Proceeds from book sales will support the BGCSF Keystone Club, a leadership development program for teenagers.

We’re often asked about the benefits of engaging youth as documenters of daily life in the communities where they live. Here’s what we say:

- Youth crave learning experiences that have relevance, meaning and purpose.

- When youth document daily life in their communities, it deepens and makes more tangible the concept of community. They get to know the people, the history and the current daily experiences that make their community vibrant and unique.

- The process of deciding what they will document, the stories they will tell and the photos they will take, and writing, editing, organizing what they have gathered introduce invaluable academic skills (rarely part of any school curriculum).

- Creating a product (in this case a book) for a public audience raises the stakes with regard to quality; brings youth the visibility and credibility they deserve; honors youth as knowledge creators, not just for those close at hand but across the globe.

We’re also asked, predictably, what it takes to create a book like this. We offer a how-to-guide for schools, adaptable to youth serving programs, along with a virtual library of many of the books published to date.

Barbara Cervone, Ed.D, is president and co-founder of What Kids Can Do and its nonprofit publishing arm, Next Generation Press. She has championed powerful learning by our nation’s adolescents for more than 40 years as a school designer, researcher, activist, grant maker and writer.

To share your story from the field, please click on YouthToday.org/from-the-field.

More stories related to this one:

Counting the Homeless Kids in Atlanta

Low-Income, Homeless Teens Use Art for Job-Readiness

Documentary on Homeless Teens in Chicago Aims to ‘Show the Struggle’