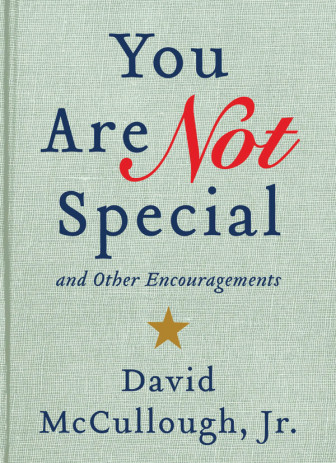

You Are Not Special: … And Other Encouragements

You Are Not Special: … And Other Encouragements

David McCullough Jr.

HarperCollins Publishers (2014)

355 pages

What’s the matter with kids these days? What’s the matter with parents? Don’t get David McCullough Jr. started.

In “You Are Not Special … And Other Encouragements,” McCullough, a longtime Wellesley (Mass.) High School English teacher, gives readers an earful. He denounces a conspicuous achievement-obsessed America that kicked aside education for education’s sake. He blasts a culture that declares all children exceptional and leaves them expecting effort-free success. He frets over lost joy — for unstructured learning and playing — and lost respect for ordinariness and everyday work.

McCullough, not to be confused with the Pulitzer-winning historian David McCullough who has written books about John Adams and the Wright Brothers, achieved instant, inadvertent fame when a video of his June 2012 commencement speech to students went viral. The address, which included the “you are not special” line, has been viewed more than 2.5 million times on YouTube.

The book, which expands on the speech’s message, arrived just in time for this year’s graduation season. McCullough hopes some new high school grad, his declared target audience, will put down the iPhone-laptop-tablet, read his book and reach for another. This is a lot — probably too much — to ask the tl;dr (too long didn’t read) generation, who would wince at the length of this review, let alone a 300-page rumination. And cynics of any age would declare McCullough’s yearning for a simpler, pregadget yesteryear as archaic, or weird.

But McCullough writes earnestly, using his own pedagogical and parental struggles (as a father of four) to frame his arguments. He enlists a parade of literary illuminati — Shakespeare, Homer, Crane, Melville, Twain, Steinbeck — to add color and gravitas. And he delivers a hopeful message: We can stop overstriving and start living, if we let ourselves.

McCullough gets worn out watching his students zip from Advanced Placement courses to cello lessons to sports showcases only to stagger home with French vocabulary lists, chemistry lab logs and whatever else is wedged into their already overfull backpacks.

“None of this is their idea of a rocking good time,” he writes, “A rocking good time is their idea of a rocking good time.”

Kids aren’t having fun yet, but it doesn’t matter, McCullough said, because achieving is all. It’s no wonder some of them crib thesis sentences or supporting quotes, or more from websites. You’d have to be a monk to resist, he writes.

If their children’s borrowed scholarship fails to impress, parents step in. Course work too hard? Push for softer standards. Teacher issue a B? Lobby. One father said his son’s entry to a name-brand college would be dashed if his report card didn’t reflect a “commitment to success.” Couldn’t McCullough just play ball and change the grade?

No, he said.

“How are you defining success?” he asked the dad.

Perhaps, McCullough suggests, parents see children as a do-over, a chance to undo mistakes and create a perfect success path. So the kid’s track record, he argues, becomes a referendum on parenting aptitude.

“The children’s blue ribbon is therefore the parent’s blue ribbon,” he writes. “The father or mother can then turn around and wave the science prize, the local sports page profile, the Duke acceptance letter at the neighbors, at his or her own parents, and say, ‘Ha! See?’”

McCullough offers outs from the achievement treadmill. Because Division I sports scholarships are rare, he encourages kids play for fun; he fondly recalls pickup pond hockey games with friends of varying aptitudes.

Because the chances of getting into Harvard are supersmall, and costs are superbig, McCullough suggests pursuing knowledge elsewhere. Head to a state school and pocket the tuition difference: Amherst costs $100,000 less and is still excellent. Or, radically, skip college altogether. Rent a room in Paris, or Mumbai, get a job in a shop and learn the language, he suggests. Make yourself an expert on something, through reading and practice. Or, my favorite, head to the public library and don’t come out.

“For thirty-two months, sit there and read, sweep the shelves clean,” he writes. “Demand much of yourself.”

After McCullough waxes philosophical and hypothetical, he gets existential. Life is finite, he says, even if you’re a young invincible with college, and all else, ahead of you. So enjoy it, he asserts, every minute.

“Every stage of life is a pleasure, or can be, because it is part of the full arc of experience,” McCullough writes. “This is our challenge, which requires strength and heart and imagination.”