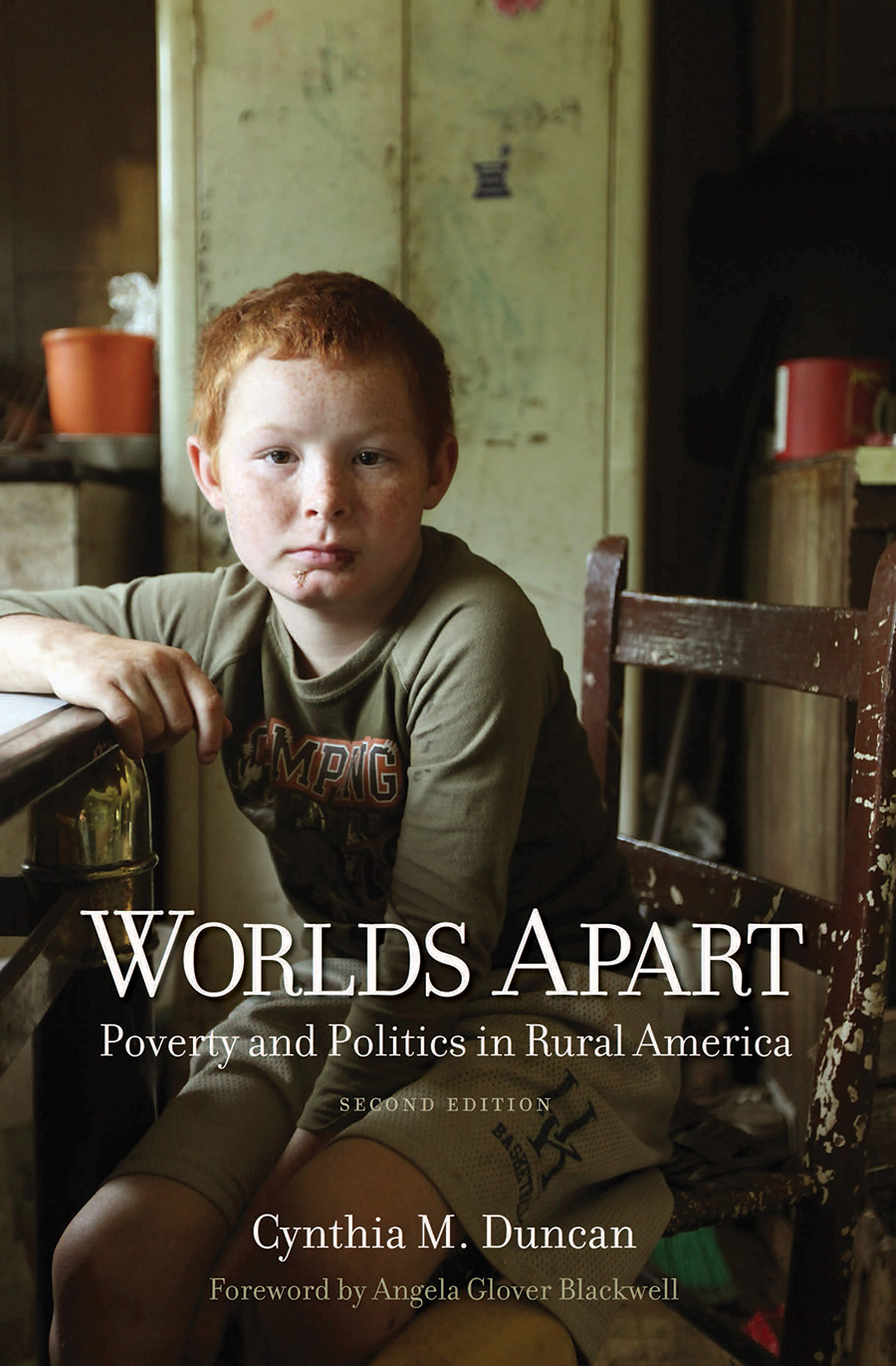

Worlds Apart: Poverty and Politics in Rural America

Worlds Apart: Poverty and Politics in Rural America

Cynthia M. Duncan

Yale University Press, 2014

304 pages

“Why do some families stay mired in poverty generation after generation, and why are some regions of the country chronically poor and depressed?” Between 1990 and 1995, Cynthia M. Duncan spent every spring, summer and winter break from teaching at the University of New Hampshire in communities in rural Central Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta and northern New England studying these questions. In a Studs Terkel-like fashion, Duncan and her team interviewed more than 350 people in sessions often lasting several hours and analyzed county-level data from 1890 to 1990 “to understand poverty and underdevelopment, the families who were persistently poor and the communities that did not change.” She asked for them to tell their stories about the community, who has power and how is it used, how people treated one another and their thoughts about the future. In stark contrast to the vibrant rural northern New England community, Duncan discovered in Central Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta a clear demarcation between the haves and have-nots and a feudal-like culture that is characteristic of other chronically poor and rural communities. For this research and book, “Worlds Apart: Why Poverty Persists in Rural America (Yale University Press, 1999) Duncan received in 2001 the American Sociological Association’s Robert E. Park Award in 2001.

Forward almost 20 years and Duncan is wondering what if anything has changed. For the second edition of “Worlds Apart” published in 2014 that is being reviewed for this issue of Youth Today, Duncan revisited these same rural areas to conduct 120 follow-up interviews. Duncan’s “Worlds Apart: Poverty and Politics in Rural America” does not read like a sequel dependent upon knowing the plot or characters from the previous book — it is a hugely informative volume that stands on its own merits. For those who are familiar with the first edition, the follow-up study must feel like a family reunion albeit one that is rather depressing because so little has changed.

Duncan discovered in Central Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta a clear demarcation between the haves and have-nots and a feudal-like culture that is characteristic of other chronically poor and rural communities.

The residents of rural Blackwell in Central Appalachia and Dahlia in the Mississippi Delta tell stories that highlight the extreme lack of resources — jobs, education and community support — that is almost unimaginable to college-educated professionals who have not experienced life in areas so devoid of capital. The bulk of these limited resources go to the haves and their families who own the local businesses, or hold good jobs, and benefit from the right connections made at church. The haves act as medieval feudal lords doling out jobs, social services and access to education to their friends and their chosen have-nots. The have-nots are beholden to the haves for even the smallest share of the limited resources. Have-not youth are more likely to drop out of school, get pregnant young, run wild and depend on welfare. The haves and have-nots culture studied by Duncan and so evident in Central Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta is mostly absent in northern New England where a spirit of civic-mindedness has created opportunities for residents and the community “has benefitted from trust, widespread participation, and steady, ongoing community investment. Again, different social relations and patterns were established early. Industry leaders lived in town next to the workers and sent their children to the same schools.”

Duncan, who was a professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire when she conducted this research, writes in a nonacademic style that is highly readable. The second edition of “Worlds Apart” includes a reprint of Robert Coles’ 1999 forward. Coles, a professor at Harvard University, was awarded in 1998 the Medal of Freedom by President Clinton for his work with underprivileged children. Chapter One of “Worlds Apart” describes the rigid class structure and corrupt politics in the coal mining community of Blackwell in Central Appalachia. Chapter Two describes the racial segregation and control by land owners in Dahlia, a town in the Mississippi Delta. Chapter Three describes how citizens came together in New England’s Gray Mountain to provide opportunity for its residents [Blackwell, Dahlia and Gray Mountain are fictionalized names to protect the identifies of these real-life communities.] In Chapter Four, Duncan assesses social change in these communities, and describes how social policies can create support for democracy and social change, encourage mobility and build civic culture to create stronger communities. In the appendix, Duncan presents graphs and bar charts illustrating key indices such as population, education, employment, family income and employment to support her argument that by allowing generational poverty the entire community suffers.

Duncan’s research provides a look into rural communities and the culture and policies that either causes communities to follow the path of Blackwell and Dahlia or Gray Mountain. Duncan points out that youth living in socially isolated rural communities in which there are few role models, where education is chaotic and subpar, and where it is highly unlikely that lots in life ever improve, share many characteristics with youth living in poor urban communities.

This is an eye-opening study for youth workers, educators and policymakers who may not have personally experienced a Blackwell or Dahlia but are witnessing the perpetuation of poverty nevertheless and are concerned about diminishing resources, the shrinking middle class and the growing wealth and prestige of the haves. Replicating Duncan’s study on a small and informal scale at a school, church or community organization by asking youth and their parents to tell their stories of the community, to identify who holds the power, to describe how people treat one another and to depict their future could provide a depth of understanding and empathy leading to improvements and change.

Additional resources about rural communities:

“Persistent Poverty Dynamics: Understanding Poverty Trends” (July 2014) by Kathleen Miller and Bruce Weber, and published by the Rural Policy Research Institute, identifies trends in poverty by county. High-poverty counties in the United States are concentrated geographically and are overwhelmingly rural.

“Why Poverty Exists in Appalachia: An Interview with Cynthia M. Duncan” lends her expertise and thoughts to understanding rural poverty.