Look around the bus stop or the local YMCA after school. Studies suggest one in five of those boisterous, smiling children — even the ones who may seem physically healthy — is suffering from a mental disorder. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, more than 40 percent of young people in the U.S. ages 13 to 17 have experienced a mental-health problem by the time they reach seventh grade.

It’s no secret that young people with mental disorders are more likely to drop out of school, be arrested, experience homelessness and be underemployed. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2011 nearly one in every six high-school students nationwide had seriously considered attempting suicide in the prior year, and about one in 13 actually attempted it.

[module type=”aside” align=”right”]According to one 2011 study by the National Institute of Mental Health,

the majority of youngsters who received treatment for behavioral or emotional problems had fewer than six visits with a provider during their lifetime, rather than the regular ongoing care that is often needed to resolve serious problems.

[/module]

Yet the vast majority of young people with mental disorders do not receive sufficient services. Many receive no treatment at all, and even children with serious disorders who do get connected with services rarely have adequate follow-up. According to one 2011 study by the National Institute of Mental Health, the majority of youngsters who received treatment for behavioral or emotional problems had fewer than six visits with a provider during their lifetime, rather than the regular ongoing care that is often needed to resolve serious problems.

Why? What keeps millions of children from receiving mental health services?

The biggest barrier to seeking treatment can be summed up in one word: stigma.

“People don’t see it as an illness like they do with physical ailments,” said Laura Brey, vice president for strategy and knowledge management at the School-Based Health Alliance, which represents the nation’s 2,500 on-site school health clinics. “And it’s looked down upon to see a mental-health provider. People don’t want to tell anybody.”

Stigma, especially among minority populations or recent immigrants, is often enough of a deterrent to keep youngsters from treatment. But there are numerous other factors, according to Sharon Stephan, co-director of the National Center for School Mental Health. “Some of it has to do with poor past experiences with the mental-health system. There are also logistical concerns: transportation and child care.”

The U.S. also lacks sufficient child mental-health specialists. “Child psychiatrists are incredibly limited, particularly in rural geographic areas,” said Stephan. By 2015, the American Psychiatric Association predicts a shortage of about 22,000 child psychiatrists. A lack of professionals who speak languages in addition to English may also magnify the treatment problem, according to the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.

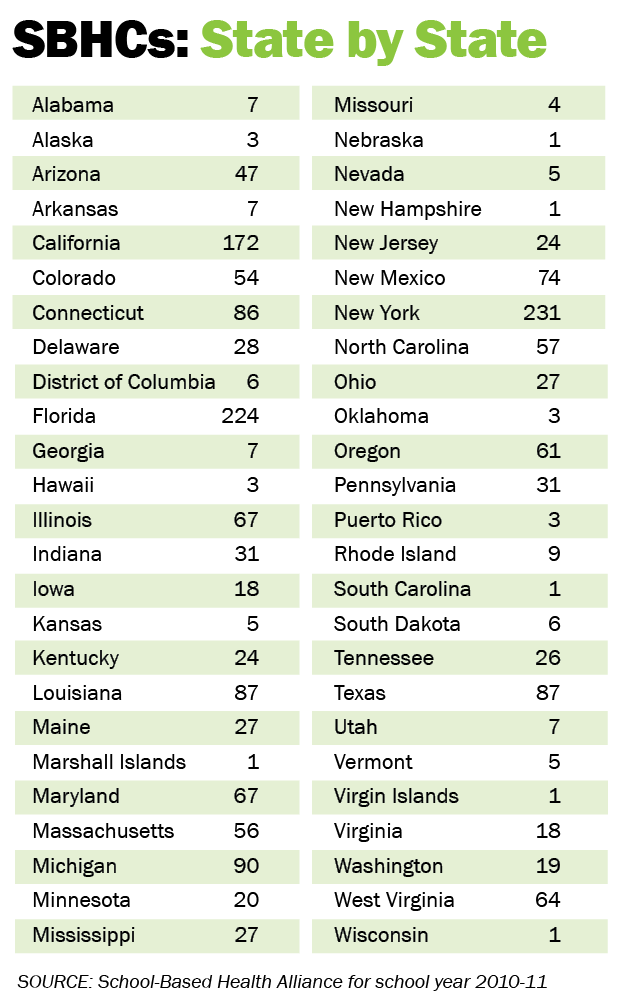

In light of these widespread treatment barriers, it’s a wonder there aren’t more comprehensive school-based health centers across the country. These on-site primary care clinics serve an estimated 2.5 million children, but that’s a tiny percentage of the combined public and private school enrollment, which reached nearly 55 million last year, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Even in states with a large number of school health centers, such as California, coverage tends to be spotty. At last count, there were 231 centers throughout the state, but about half the counties have none. Centers are concentrated in urban or suburban areas, leaving large swaths of the more rural northern and eastern counties uncovered.

“I don’t know how other school districts can function without having something like a wellness center in their school,” said Wendy Snider, wellness coordinator at Thurgood Marshall High School in San Francisco. According to Snider, about 60 percent of the school’s 475 students come to the center for some type of service each year.

According to Brey, it takes leadership and community desire to get a year-round, school-based health center (SBHC) going. She said the annual budget to run a fully-staffed center offering comprehensive primary care and mental-health services to about 1,000 students is $250,000 to $350,000 at minimum.

SBHCs serve a small percentage of children. Even the more widespread comprehensive school mental health model, in which a community provider partners with a school to bring services on-site, isn’t taking care of everyone. According to the National Center for School Mental Health, about one-third of U.S. schools limit their mental-health services to what can be provided by school-employed staff, who are often stretched to the limit.

According to the most recent data available from the National Association of School Psychologists, in 2004 there were an estimated 29,000 psychologists employed in public schools, with a student to psychologist ratio of more than 1,650-to-1. School counselors are similarly strapped for resources.

In the meantime, troubled children who could have been helped to recover through early diagnosis and intervention often begin a spiral downward. By the time they reach adulthood, that early neglect could result in lifelong mental-health problems.

Back to main story “Schools Remove Barriers to Mental Health Treatment”

Resources

The School-Based Health Alliance, celebrating its 20th anniversary, is the national voice for school-based health centers. The 2015 National School-Based Health Care Convention will take place June 16-19, in Austin, Texas. The website offers information for setting up a school-based health center and complete list of state affiliates.

Phone: 202-638-5872

Email: info@sbh4all.org

Since its inception, the Center for School Mental Health has been committed to promoting student education, health and mental health through a shared family-school-community agenda. The annual Conference on Advancing School Mental Health will be held Nov. 5-7, 2015, in New Orleans.

For more information, contact:

Center for School Mental Health

UMB Telephone Switchboard: 410-706-3100

To see archived webinars, reports and white papers, visit: csmh.umaryland.edu/

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

SAMHSA makes grants that support programs for substance-use disorders and mental illness through the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment and the Center for Mental Health Services. samhsa.gov/grants

Phone: 877-SAMHSA-7 (877-726-4727), 800-487-4889 (TDD)

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

Suicide has many warning signs. For more information, visit the website of the American Association of Suicidology at suicidology.org.

Phone: 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255)