A&M Agrilife Extension Service

Teens ages 14 through 18 can participate in the Garden of Greatness club, often planting in their newly built beds for the first time.

Many of the teens in the impoverished section of San Antonio had never seen a garden before, let alone planted vegetables in the Texas soil.

Now they sow, tend and harvest tomatoes, cucumbers, cabbage, broccoli, squash, peppers, onions, black-eyed peas, okra, strawberries and various herbs as part of the Garden of Greatness after-school program.

The 28 teens toil in 15 garden beds on what had been a vacant lot at a now-closed Catholic school.

The program, led by the Texas A&M University AgriLife Extension Service, provides an oasis in the middle of an urban food desert – an area overrun with fast-food and convenience-store fare but lacking healthy, affordable alternatives.

A&M Agrilife Extension Service

The harvest goes home with the teens and what they don’t take home, Garden of Greatness gives to community partners or uses in their nutrition/cooking classes.

The students, in grades eight through 12, learn not only by using their newly developed green thumbs, but also through weekly lectures about urban food deserts, healthy eating and careers in science, agriculture and nutrition.

Rosemary Fuentes, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension health and wellness program specialist for Bexar County, Texas, said the after-school program plants seeds for the kids’ futures.

“We’re trying to build momentum and hoping they see that if they continue participating, they may have an inkling to say, ‘Because of this program, I really found an interest, and I’m going to go into A&M, or I’m going to go into science, or I decided I wanted to be a chef or a dietitian,’” Fuentes said.

Garden of Greatness – which works with the Christ the King Catholic Church in west San Antonio, the San Antonio Boys & Girls Club Teen Center, a 4-H gardening club and Bexar County Master Gardeners — began as a pilot program last February.

The after-school program and an in-school program in a Houston food desert have been awarded about $350,000 each as part of a five-year grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) through its National Children, Youth and Families at Risk Program.

The students take home produce they grow and, with guidance from Fuentes, prepare dishes using the fresh ingredients in an on-site kitchen.

And at the end of last school year, a master chef made vegetarian eggplant tacos, and the kids who ate them thought they were traditional Tex-Mex tacos with chicken or beef.

Like Garden of Greatness, some similar programs across the country teach kids in food deserts how to plant vegetables and make healthier eating choices.

Along with farmers’ markets, mobile food markets, bodegas selling produce and portable “pop-up” markets, such after-school programs are among a wide array of responses to food deserts that deprive today’s young people of nutrients they need to thrive.

23.5 million Americans live in food deserts

According to the USDA, an estimated 23.5 million Americans – more than 7 percent of the population – live in food deserts, and more than half of them, 13.5 million, are low-income.

The U.S. government defines a food desert as a census tract with a substantial share of residents who live in low-income areas and have little access to a grocery store or other healthy, affordable retail food outlet. The government gives funding priority to efforts that establish healthy food outlets in food deserts in urban and rural areas.

The USDA has targeted eradication of food deserts among its top goals, and first lady Michelle Obama made eliminating them a priority of her “Let’s Move!” campaign against childhood obesity.

A&M Agrilife Extension Service

Teen club members work hard to fill the beds with soil before they can plant and harvest.

Children, who are often attracted to junk food, are especially vulnerable when they live in food deserts. And they are particularly vulnerable to health risks associated with food deserts, including obesity, which makes them more susceptible to significantly higher rates of Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease at younger ages, said Jill White, nutrition and dietetics program chair at Dominican University outside of Chicago.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports childhood obesity has more than doubled in U.S. children and quadrupled in adolescents in the past 30 years. In 2012, more than one-third of children and adolescents were overweight or obese.

“It’s not like we live in the Sahara where there’s no food. It’s just that the food that people do get [in food deserts] is of poor quality,” White said. “They don’t have access to fresh fruit, vegetables, whole grains.”

Link between food deserts and academic achievement

That’s particularly true in vast poverty-stricken stretches of south and west Chicago, White said.

Chicago-based researcher Mari Gallagher, who popularized the term “food desert,” has found a link between a lack of healthy food choices and school performance. Gallagher said her new study found living in a “poor food environment” — one lacking healthy, affordable and accessible food — had a greater effect on standardized test performance than family income in Wapello County in southeastern Iowa.

“So, living far from a regular grocery store, like a mainstream store, had a negative impact, and living really close to a junk-food store, like a fringe food store, had a negative impact,” Gallagher said.

Her firm has conducted numerous studies on food deserts. For example, a September 2014 study found access to quality retail grocers across Florida is strongly linked to health.

“Individuals living in places, both urban and rural, where many households reside more than a half-mile from the nearest full-service grocer and lack access to a vehicle are more likely to die prematurely from diabetes, diet-related cancers, stroke, and liver disease than individuals living where grocers are closer and vehicles are more available” after controlling for other key factors, the study said.

Hopeful signs

A&M Agrilife Extension Service

Gardens can be both functional and beautiful. Flowers serve pollinating insects — and bring joy. The teens are taught intensive gardening and companion planting methods. Diverse gardens are healthy gardens.

Signs of progress in eliminating food deserts exist: In Chicago, Gallagher said, some 640,000 people — many of them children — lived in food deserts when her firm studied them in the city in 2006. Today, that number has declined to 285,000, as more grocers move into previously underserved areas, sometimes enticed by government incentives.

The upscale grocery chain Whole Foods Market Inc. is testing its model in one of the most economically depressed and violent parts of Chicago, the South Side community of Englewood, where it plans to open an 18,000-square-foot store in 2016.

And in California’s predominantly African-American and low-income community of West Oakland, the nonprofit People’s Grocery is spinning off a for-profit company to open a much-needed grocery store.

Aaron Sachs, a communication professor at Saint Mary’s College of California whose students work with People’s Grocery on urban food issues, said the for-profit People’s Community Market is being financed by small, local investors.

“So, it’s not big investors or institutional investors,” said Sachs, who teaches a course called “Communication and Social Justice: Food Justice.” “That was an important community ideal for making sure they have community buy-in.”

Along with plenty of fresh meats and produce, People’s Community Market will offer cheap, prepared healthy food as an alternative to fast food for children and other people in a hurry.

Food deserts and poverty

“Ultimately, food deserts are a symptom, and they’re correlated with poverty,” Sachs said. “A grocery store exists as a profit organization. They make less money going into a poorer community. This, at least, is their perception.”

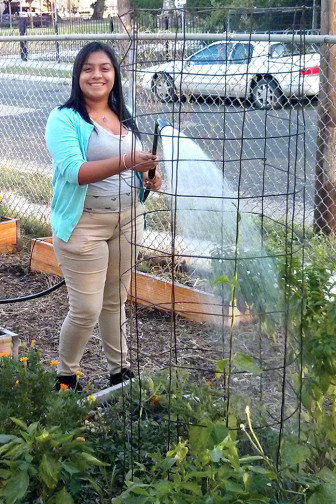

A&M Agrilife Extension Service

Miranda, a club member, shows how watering and fertilizing their gardens are some of the teens’ favorite tasks.

He noted many grocery chains have shifted to bigger stores designed to serve customers with cars, making it harder for those who rely on public transportation to get healthy foods.

In Detroit, Sachs said, so many residents have left that urban farming has gotten a huge boost because of the soaring number of vacant lots, alleviating food deserts.

In Cleveland, the Green City Growers Cooperative’s 3.25-acre, hydroponic greenhouse, built on what had been vacant lots, produces at least 3 million heads of lettuce and 300,000 pounds of fresh herbs per year.

The cooperative, which offers employees a chance to own part of it, sells to the largest food-service companies in the area, as well as to a local grocery store chain, and donates at least 1 percent of its product to the Greater Cleveland Food Bank for distribution in the city’s Central neighborhood.

And in the south Bronx in New York City, Tanya Fields runs a mobile produce market — an old school bus powered by vegetable oil.

The single mother of five, who moved to the south Bronx about 12 years ago, decided to do something about the dearth of healthy food in neighborhoods in the borough.

So she raised money through an online fundraising site and received contributions from foundations to support the South Bronx Mobile Market.

The mobile produce market, painted sky blue with bright green and purple vines, cruises through two south Bronx neighborhoods, making stops to sell fresh produce. Sometimes, it parks in front of a McDonald’s in the Mott Haven neighborhood, offering healthy alternatives to junk food.

Fields brought on a volunteer driver and relies on two full-time interns in the summer. Other than that, she pretty much runs the operation single-handedly, buying food grown locally to sell.

With the help of a New York City councilwoman, she fought to get a license to convert a 4,500-square-foot vacant lot into an urban farm and will begin growing produce, flowers and trees there in the spring.

“I wanted to be a person who turned attention to creating solutions, not being the person who walks around talking about how bad my neighborhood was,” said Fields, 34. “I wanted to be a person who talks about how resilient my neighborhood was and how we were going to harness that resiliency.”