Robert Stolarik

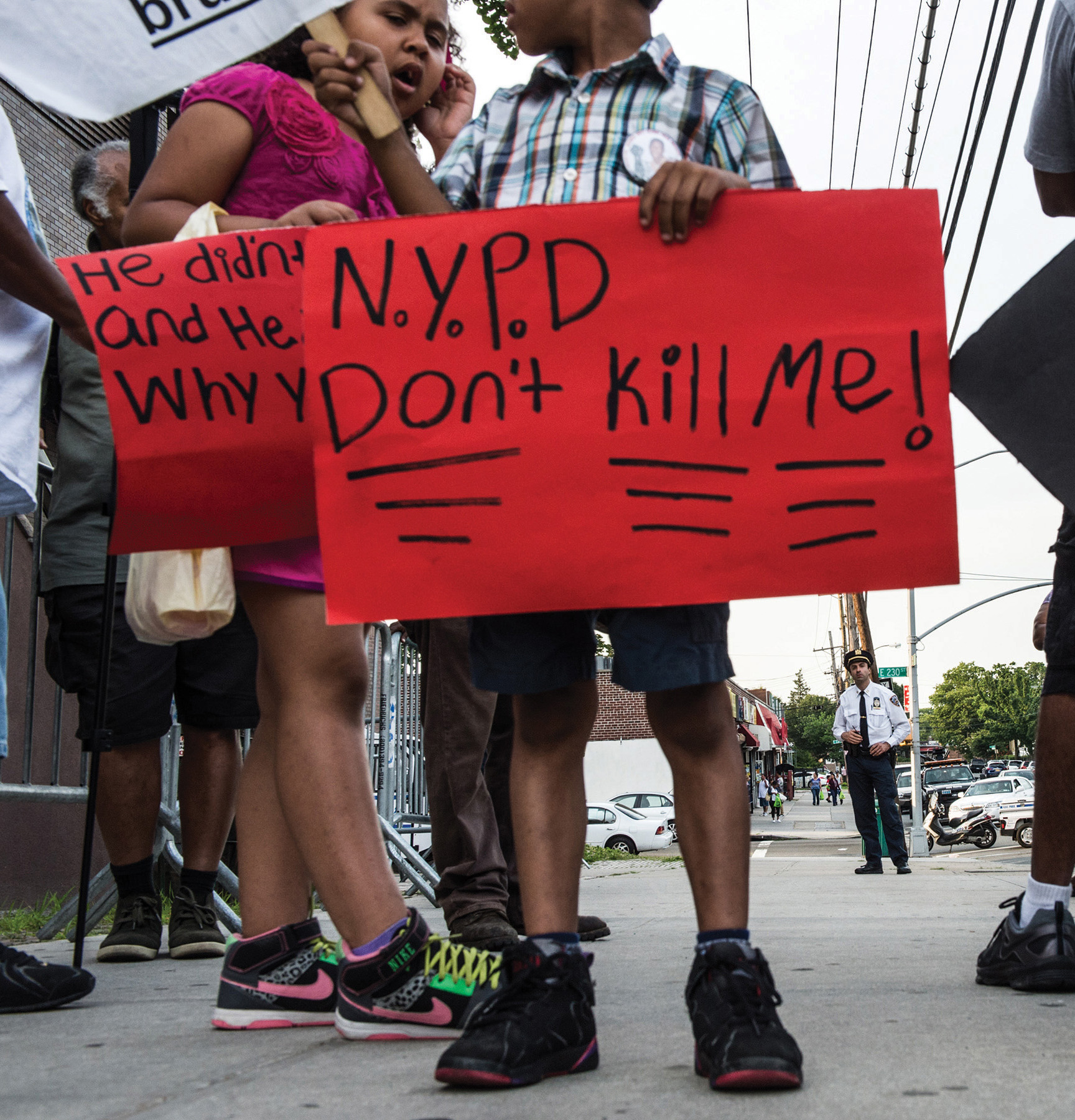

A young protester has a powerful message.

See main story “Parents Turn Pain into Policy.”

On a Sunday afternoon this past summer, a little boy who recently lost a baby tooth stood amid a throng of angry protesters marching their way from a house on East 229th Street through quiet residential streets in the Bronx to the 47th Precinct, where police brass waited behind a metal enclosure.

The little boy held a bright red sign, difficult to make out since he was so small, and the crowd obscured the message written with thick black marker. As the crowd parted, the message became clear: “N.Y.P.D Don’t Kill Me!!!” To stress the point, someone had underlined the message three times.

The little boy was one of a clutch of 50 protesters led by Constance Malcolm, whose son Ra Graham died after he was chased to his second-floor bathroom and fatally shot. The police officer who killed Graham, Richard Haste, never had a day in court. After the case wallowed in legal limbo for years, the Manhattan U.S Attorney’s office announced on Sept. 17 it was opening a civil rights investigation into the killing.

[module type=”aside” align=”right”]“They don’t need these real-life stories told to them by the police, or by the district attorney’s office or some bureaucrat from the city. These young people aren’t stupid. They feel like those people are coming at them with a different agenda. If the city would help us go out and reach out to these young people … we could really make change on this whole culture of violence.”

Taylonn Murphy, father and activist

[/module]Malcolm has spent years as part of this loose network of parents who dedicate almost all their free time to the twin pursuits of finding justice for their child and working for broader reforms to make sure another parent does not find herself in the same predicament. Many of the people who attended her event are familiar from other events paid for and organized by other members of the club no one wants to join. She was there the night at the salon. (See main story.) She said so much of her passion is wasted just on scrambling to deal with logistics.

“It gets frustrating,” she said. “I have dedicated my life to this since my son was killed by the NYPD. But without the structure, or the resources, it gets to a point where you feel like all your passion goes into just getting things planned, and none of it goes into making sure this doesn’t happen again.”

Even though her son was killed by police and not by another young person, Malcolm sees her story as connected to the other parents who are out there fighting to give meaning to the seemingly senseless death of a child.

Police overreach is the logical extension of what parent activist Taylonn Murphy calls the epidemic culture of violence afflicting the housing projects and poor neighborhoods across New York City, from the dense apartment towers along the beachfronts of Far Rockaway, Queens, to the low-slung row homes and elevated trains of the north Bronx.

Malcolm said when the city fails to listen to the advice of the parents who have buried their children, like Murphy, the violence persists. Instead of trying to prevent violence, the city responds with more force. When raids, additional police and more street confrontations are the only answer, she said, then more unarmed young men like her son are bound to get gunned down.

“I was not trained for this,” Malcolm said after leading the protesters back to her house. “This was not supposed to be life. But when my son was killed I could not just sit back and do nothing. I had to do something. I had to do something not just for Ramarley, but for all the other young people out there. If we don’t do something to end this violence, to change the way things are, who will?”

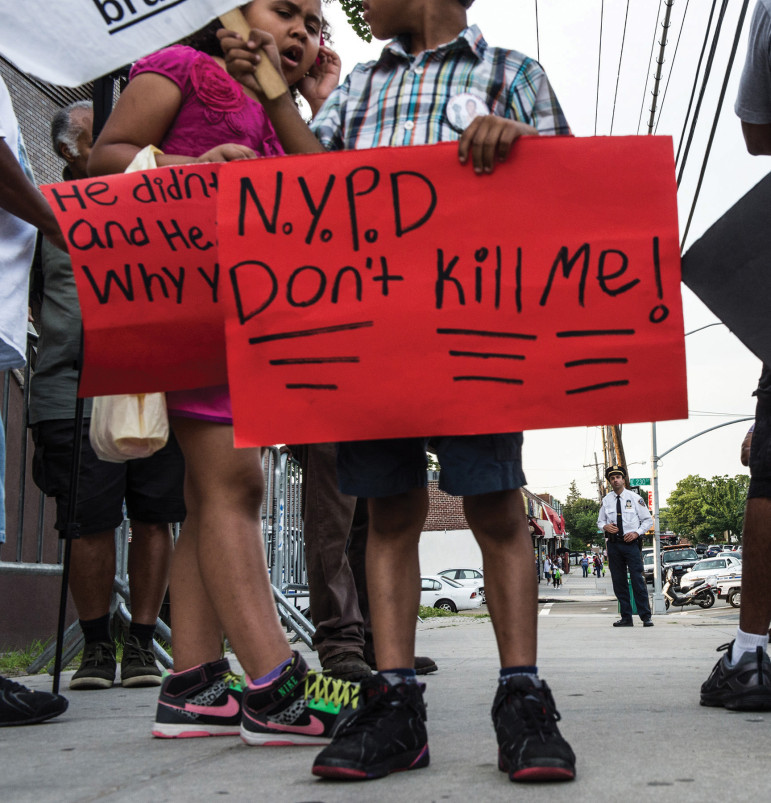

Robert Stolarik

The group of protesters, organized by Ra Graham’s mother Constance Malcolm, make their way through the Bronx to the 47th Precinct.

Return to main story “Parents Turn Pain into Policy.”