From The Chicago Bureau:

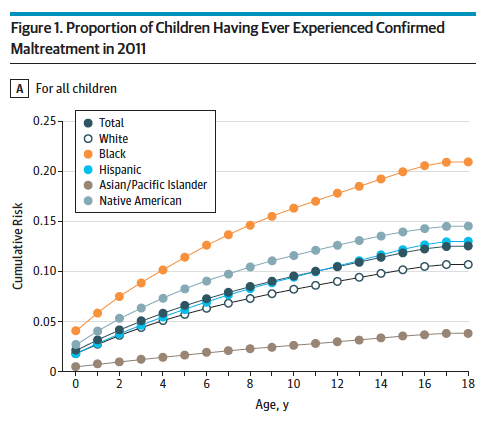

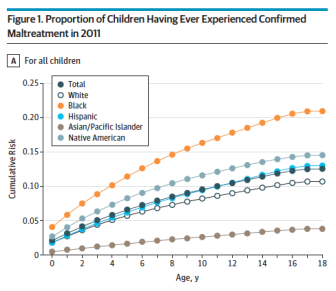

Approximately one in eight children will suffer maltreatment by the time they turn 18, according to a recent study. The risk is even higher for black children, one in five of whom will experience confirmed abuse or neglect at some point in their childhood or adolescence.

“In other words, black children are about as likely to have a confirmed report of maltreatment during childhood as they are to complete college,” the study authors wrote, comparing this data to that from a previous study. The authors, led by Yale researcher Christopher Wildeman, also noted the increased risk of physical and mental health problems among children who have experienced maltreatment.

“The results from this analysis—which provides cumulative rather than annual estimates—indicate that confirmed child maltreatment is common, on the scale of other major public health concerns that affect child health and well-being,” they wrote.

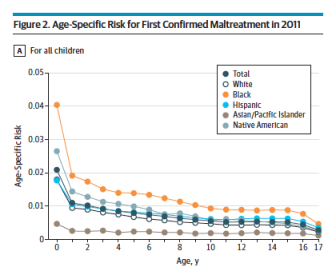

Child maltreatment data, which includes confirmed cases of abuse or neglect (about 80 percent of cases are neglect), are usually presented in terms of how many children suffer maltreatment each year, which is approximately 1 percent of all children and teens. But that figure does not capture cumulative rates over a person’s entire childhood.

“We want to know about annual child maltreatment rates because they let us see how maltreatment changes in a short time period, and also because it gives us a sense of how large we could expect caseloads to be for CPS [Child Protective Services] workers,” Wildeman said. “Cumulative risk estimates give us a better sense for how important these events are for children throughout the life-course and, in so doing, help us get a sense for how serious a problem child maltreatment is.”

“We want to know about annual child maltreatment rates because they let us see how maltreatment changes in a short time period, and also because it gives us a sense of how large we could expect caseloads to be for CPS [Child Protective Services] workers,” Wildeman said. “Cumulative risk estimates give us a better sense for how important these events are for children throughout the life-course and, in so doing, help us get a sense for how serious a problem child maltreatment is.”

Wildeman’s team used data from more than 5.6 million confirmed cases of maltreatment between 2004 and 2011 that were reported in the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Child File. These were extrapolated to the full population of children in the US using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Their findings revealed that approximately 12.5 percent of all children would suffer a reported and confirmed case of abuse or neglect by age 18, with girls suffering slightly more (13 percent) than boys (12 percent).

Although these rates seemed a little high to Kate Naylor, a licensed marriage and family therapist associate, she said it’s not out of the realm of possibility. The reasons for neglect, she said, stem from a lack of support.

“I most commonly see child maltreatment occurring due to overwhelmed, under-supported parents – especially in terms of neglect,” Naylor said. “Maltreatment is often the result of both a frustrated child and a frustrated parent not having the emotional, mental or physical resources to cope with a stressful situation in a healthy way.”

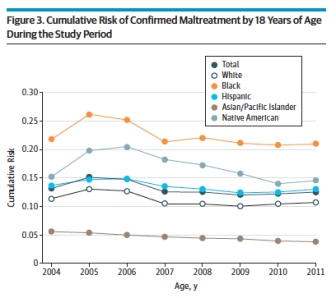

When the researchers analyzed the numbers for different racial and ethnic groups, they found large disparities from one group to another. Approximately 21 percent of black children, 14.5 percent of Native American children, and 13 percent of Hispanic children will suffer confirmed maltreatment in their childhood, compared to 10.7 percent of white children and 3.8 percent of Asian/Pacific Islander children.

These figures make sense within the context of what’s already known about child maltreatment. Research links the risk of child maltreatment to both child and family characteristics: children’s age, disability status and gender, as well as the parents’ or families’ race, education, socioeconomic status, family structure, domestic violence and drug use, Wildeman said.

Neighborhood-level characteristics can also play a role, and these links provide clues about why the risk is higher for some racial groups.

“For African American children, I think the story is clear: Because of the serious structural disadvantages their parents face – spilling out into the economic domain, their personal relationships and their neighborhoods – they face by far the highest cumulative risks of confirmed maltreatment,” Wildeman said.

In other words, he said, it’s less likely that black parents have cultural differences in parenting practices that contribute to maltreatment than that they live in neighborhoods and share various characteristics (such as being poor or facing other structural constraints) that already increase the risk of abuse and neglect in the home. There is also some, albeit controversial, evidence that black families experience bias from Child Protective Services.

In addition, overrepresentation of some ethnic groups in lower income demographics could account for some of the differences in rates by ethnicity. Maltreatment is highly correlated with poverty and lower education levels, Naylor said. If one demographic group is overrepresented in poverty measures, that group is likely to be overrepresented in maltreatment measures as well.

The comparatively much lower rates for Asians and Pacific Islanders are harder to account for, however, especially given how heterogeneous it is. Though it’s likely their rates truly are lower, it is also possible that under-reporting could account for the low percentage since this study could only capture confirmed cases in which CPS receive a report, visits a home and finds sufficient evidence to conclude that abuse or neglect occurred.

Both Naylor and Wildeman emphasized that the solution to reducing risk of maltreatment is providing more support to families.

“The things that lead to child maltreatment tend to not be severe psychological problems on the part of parents but simply being overwhelmed and in neighborhoods that have insufficient resources to support them,” he said.

One such form of support could include nurse home-visiting programs “because they most help parents with the youngest children adjust to dealing with the stresses of parenting,” he said.

In fact, the study found that the youngest children have the highest risk of experiencing maltreatment. Approximately 2.1 percent of children will have a confirmed case of abuse or neglect by age 1, and 5.8 percent by age 5. But programs aimed at younger children would just be a start.

“Parents, children and communities would all greatly benefit from education around parenting, healthy relationships and emotion coping skills, as well as support programs like parenting hotlines, support groups and more accessible child care,” Naylor said.

She said that child rearing has historically been a community effort until recently.

“Many parents are doing it alone, while working long hours, with no instruction manual,” she said. “For most of our existence humans shared the responsibility of raising young children, and it was never meant to be something we had to do all alone. I think we are seeing the effects of that.”