Photo courtesy CPEP

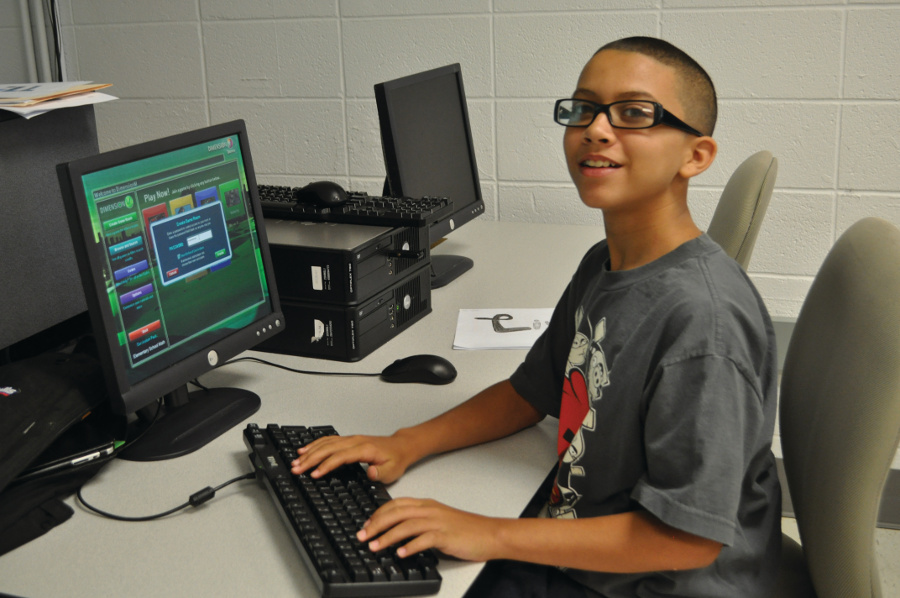

A summer program student gets ready to use the DimensionM math video game for math practice at the University of Hartford.

In Boston, fourth-graders in a public school spend summer mornings reading, talking about and researching ecosystems, then head out to Massachusetts marshes and wetlands in the afternoon to get close-up with what they’re learning.

In New Haven, Conn., students in the nonprofit Connecticut Pre-Engineering Program learn engineering principles through video games, then build an earthquake-resistant structure using Popsicle sticks, gum drops and aluminum foil.

Photo courtesy CPEP

Students work on teams in both hands-on and digital-media project challenges at the University of Hartford program. Along the way, they develop skills such as collaboration, creativity, critical thinking and digital literacy.

In Newark, N.J., low-income students in a nonprofit program called Horizons National plant seeds in an organic rooftop garden, then weeks later harvest vegetables, bring them into a test kitchen, cook them and eat the appetizing results.

In summer programs like these across the nation, education masquerades as fun, helping to counter what’s known as summer learning loss, the summer slide or brain drain – the loss of reading and math skills during the summer months.

It happens every year, as sure as school lets out for the summer and kids turn their attention to other pursuits, and summer learning loss is particularly pronounced among low-income students.

In reading, research shows, low-income students lose more than two months of grade-level equivalency during the summer; whereas, middle-class students make slight gains. Most children lose about two months of math grade equivalency during the summer.

Achievement gap and accumulative loss

The losses in reading achievement are particularly disturbing, given they’re cumulative.

That means a low-income student typically lags an average of nearly three grades behind her middle-income peers in reading by the end of elementary school, mostly due to summer learning loss, explained Johns Hopkins University researcher Karl Alexander.

Photo courtesy Springboard Collaborative

A teacher helps a family practice how to ask questions while reading at the Springboard Collaborative summer program at Wissahickon Charter School in Philadelphia.

Alexander and his colleagues tracked 800 low- and middle-income Baltimore City Public School students for 25 years, beginning in 1982, and found that by ninth-grade, two-thirds of the achievement gap between the two income groups could be traced to summer slide during their elementary school years.

This Johns Hopkins study found that both low- and middle-income students mostly kept pace during the school year, but low-income students lost ground during the summer.

“Middle-class families continue to build up skills that show up on achievement tests during the summer months; poor kids don’t,” Alexander said. “That’s where the summer slide imagery comes in.”

What accounts for the differences?

Alexander, who said the Baltimore findings reflect national research, notes that many of the low-income students’ parents never finished high school themselves and thus can struggle to help their own children succeed in school.

Middle-class kids also tend to have books in their homes; whereas, lowincome children often do not, and lowincome children are less likely to see their parents reading and thus modeling the habit. Another factor: differences in access to enriching experiences like family outings to cultural and historical sites, summer camps, music lessons and summer travel.

Poor kids also more often live in unsafe neighborhoods where they don’t get outside to play as much their more resourced peers and have less access to libraries because of limited hours or because their parents have no vehicle to drive them to one.

“All that good stuff that we just take for granted isn’t available to poor children,” said Alexander, who is also a sociology professor and chairman of the Department of Sociology at Johns Hopkins.

Engaging Programs Help Stem Summer Learning Loss

The next best alternative, say Alexander and other experts, are vibrant, engaging summer programs that help stem summer learning loss.

The National Summer Learning Association (NSLA) — a Baltimore-based nonprofit that advocates more summer learning programs, particularly for lowincome children — notes a century’s worth of research shows kids who aren’t involved in summer learning pursuits score lower on standardized tests at the end of summer vacation than they did at the beginning of summer.

|

“The thing that stands out time and again is access to books over the summer and encouragement for children to read and to receive support in building up their reading skills… If you can’t read at an appropriate level, everything else in school is just completely mysterious.”

Karl Alexander • John Hopkins University |

Sarah Pitcock, NSLA’s CEO, said the elementary school years are pivotal.

“What happens in elementary school is you’re learning all those really foundational skills, particularly in reading,” Pitcock explained. “From kindergarten to third grade, you’re learning to read and then, in theory, from fourth grade on, you’re reading to learn.

“That’s why you see such a focus now on fourth-grade reading proficiency because it’s such a tremendous predictor of life success,” she said.

“So if kids are falling behind each summer in those early years of education, they’re not catching up. Their teachers are not able to bridge that gap during the nine months of the school year, so each year they fall further and further behind. If you can’t read, you can’t succeed in virtually any of your other academic classes.”

Pitcock points out the summer learning loss can leave kids five or six years behind by ninth grade, prompting some discouraged students to drop out.

Summer learning shortage

Unfortunately, demand for summer learning programs far exceeds availability.

Indeed, the Afterschool Alliance, a Washington-based nonprofit that advocates for quality out-of-school time programs, found in a 2011 study sponsored by the Wallace Foundation that only 25 percent of U.S. school-age children (about 14.3 million) participated in summer learning programs. Based on parents’ responses to a survey, 56 percent of non-participating children (about 24 million) would enroll in a summer program if one were available.

The Alliance also found an overwhelming majority of parents support public funding for summer learning programs, with support strongest among low-income and minority parents.

Another 2011 study, by the RAND Corp., found cost is the main barrier to implementing and sustaining summer programs.

‘A huge equity issue’

The shortage of programs leaves a disproportionate share of low-income children without summer learning opportunities, compared with their middle- and upper-income peers.

“I think it’s a huge equity issue,” said Jodi Grant, executive director of the Afterschool Alliance. “For most middle- and upper-class kids, they’re doing educational things over the summer.

“There’s a gap between those kids — where parents are creating opportunities and paying for opportunities — and kids who are, if they’re lucky, sitting home and watching TV. And I think there’s an issue, too, with physical activity where kids need to be out and running around, and if you don’t live in a safe neighborhood or you don’t feel safe letting your kid run around when you are at home, kids are stuck indoors.”

Elsewhere, a growing number of innovative programs provide summer learning opportunities for kids.

Learning By Building Model Rockets, Sailboats

At 33 Horizons National programs in 13 states, students start in kindergarten and most of them return for summer sessions each year through eighth grade and, in some programs, each year through high school. The students participate in mostly project-based learning in the mornings, then apply what they have learned.

Students in a New Canaan, Conn., Horizons program aim high – building, then shooting off model rockets and measuring the altitudes reached. In Rochester, N.Y., Horizons students build miniature sailboats out of balsa wood, then sail them in a stream in a STEM activity.

In all the Horizons programs – held at K-12 schools or colleges with which the non-profit partners – kids learn to swim, with their teachers in the pool with them. That’s designed to boost the children’s confidence that they can master new challenges inside the classroom and out and to improve math skills, as they race and measure times and distances.

Students also take weekly field trips, from visits to museums, historic sites and nature centers to sailing expeditions and journeys to other cities.

“Horizons tries to … essentially provide for low-income kids what higher-income families are able to provide themselves,” Horizons CEO Lorna Smith told Youth Today.

And the tuition-free program reports dramatic results. Rather than two or three months’ summer learning loss many other low-income children experience, Horizons says its students have gained an average of two to three months in reading each of the past six years.

“Horizons offers our kids a chance to really be good at learning and to feel successful,” Smith said. “We provide a lot of opportunities for kids to succeed and thrive. And, you know, it works. It’s just a great way to use the [summer] time that would otherwise be hurting their future to actually accelerate their learning and propel them toward a better future.”

Relying On Parents to Help Teach Children

Other programs enlist parents to help counter summer learning loss.

In Philadelphia, the non-profit Springboard Collaborative offers an intensive, five-week summer literacy program for pre-K through third-grade students and their families.

The teachers visit the homes of each of their 15 students to bring parents on board and tell them what to expect.

Teachers conduct daily, half-day literacy instruction with students grouped by reading level rather than by grade level.

And the teachers lead weekly workshops for parents during which the teachers help parents pick books on their child’s reading level and offer tips on what to do before, during and after reading with their child.

“We view summer learning loss as a symptom of a deeper problem: Low-income parents have been excluded from the process of educating their kids,” Springboard founder and CEO Alejandro Gac-Artigas said in an e-mail. “Parents are both the most powerful and most underutilized natural resource in education.”

Since its launch in 2011, Springboard has grown from 42 students – it calls them “scholars” – to 642, and they have not only erased the summer slide but gained an average 3.3 months during the five-week summer session, the non-profit says.

Engaging kids in reading and ensuring they read at grade level is crucial in the early elementary school years, says Alexander, the Johns Hopkins University researcher.

“What I can say from the research evidence is that the thing that stands out time and again is access to books over the summer and encouragement for children to read and to receive support in building up their reading skills,” Alexander said.

“And if you can’t read at an appropriate level, everything else in school is just completely mysterious. Everybody needs strong reading skills. That’s foundational.”

Financial supporters of Youth Today may be quoted or mentioned in our stories. They may also be the subjects of our stories.