By Marianne Modica

By Marianne Modica

Morning Joy Media

297 pages.

The “‘N word’ equivalent for white people is ‘the R word,’” says Marianne Modica in her Foreword to this young adult novel. People cringe when they are called “racist.” A professor at Valley Forge Christian College, Modica trains future teachers in multicultural education. Racism is expressed subtly today, she says, “in ways that are so much a part of our lives that we don’t notice them.”

Through the eyes of Rachel, a sheltered Italian-American high school junior in a Philadelphia suburb who befriends city youths of color, Modica’s novel explores cultural misperceptions among groups who are isolated from one another. It touches on inequalities in educational facilities and long-standing racial hatreds, on a personal and societal level.

Raised by her grandparents and policemen uncles Tommy and Johnny, Rachel has no memory of her policeman father, who was killed in the line of duty, or her mother, who abandoned her. When her best friend moves away, Rachel joins an after-school club run by Sister Gloria, an African-American nun from “The Tolerance Project.”

What Rachel doesn’t tell her overprotective family is that the meetings are not at school; a special bus takes Rachel to Sister Gloria’s office in the city near the other students’ schools. Rachel is the only white person in the group. Spanish-speaking Sandra comes from Northside School. Three African-Americans – Henry and brother-sister duo Darrin and Damara – go to Jefferson. Only large, friendly Henry, who tries to put Rachel at ease, has heard of Rachel’s school, Coventry Township.

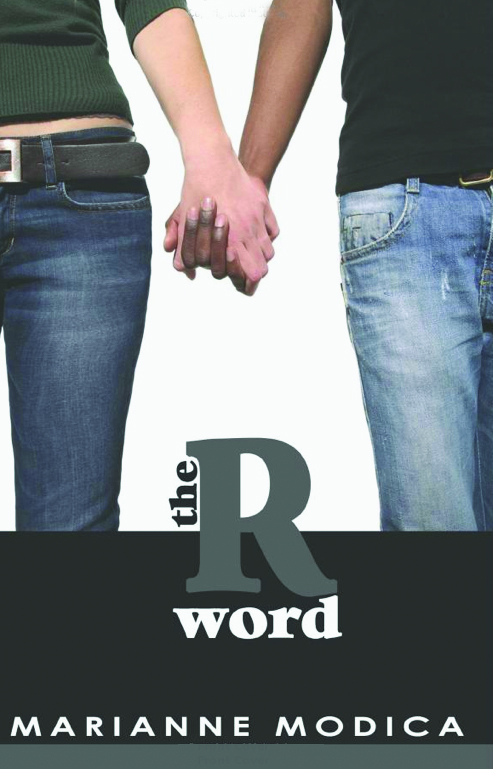

Naming themselves Colores (Spanish for colors), the group discusses service projects. They decide to help with a Saturday fundraising fair at Damara’s church, but Rachel has no transportation. When Henry offers to drive her in his beat-up car, Rachel panics at the thought of her family’s reaction to a black guy taking her into the city. Henry agrees to pick her up at the mall, which becomes routine.

Henry finally asks Rachel if she is keeping him away from her house “because I’m a guy or because I’m black?”

“Both,” Rachel admits, calling her family “old-fashioned.”

She is devastated when Henry uses the word “racist,” asking, “What else would you call it? They don’t want you hanging around with a black guy.”

Rachel realizes she has been lying not only to her family and friends, but also to herself. “Before I met you all, I never thought about race,” she says. “I’m sorry.”

This turning point in their relationship – and Rachel’s consciousness – triggers further life-changing events. The watershed moment is Colores’ tour of one another’s schools: Rachel is outraged – and her friends are stunned – by shocking disparities between the modern suburban school and the decrepit city schools. The group’s letter of protest to the school board spurs community efforts to address these gaps.

When Rachel’s relationships with her new friends are revealed to her family, she learns of the origins of her family’s hesitancy about embracing other races. Rachel and Henry have realized they’re in love; their families grow to accept it.

Overlapping catastrophes seem rushed at the end, and details are missing about Henry’s acceptance by Rachel’s family. An epilogue seems too happily-ever-after.

Yet Modica’s sensitive handling of the challenges and rewards of Rachel’s intercultural friendships encourages today’s youth, who are more accepting of interracial relationships than previous generations.

Novels with a strong mission can become preachy, but Modica makes readers believe in her characters. This absorbing story moves at the brisk pace that teenagers enjoy, and its characters behave like people they know.

Modica provides discussion questions for classroom or workshop use. An Afterword anticipates her critics: For those who think school desegregation is complete, she explains that her fictional schools represent real schools “in urban/suburban school districts around our country.” Today’s students assume that “racism is no longer a problem,” Modica concludes. “Because many of us think we’re not supposed to talk about race anymore, racism is much harder to see now than it used to be, and things that are hard to see are even harder to change.”

Contact: (610) 256-2906

Cathi Dunn MacRae covers intellectual freedom issues for Voice of Youth Advocates (VOYA); she is its former editor-in-chief. She also specializes in teen writing and reading.