A costumed vampire reaches for the doorbell and squeals, “Trick-or-Treat!” In one hand he holds a candy bag; in the other, an orange cardboard box that says “Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF.”

A candy bar plops into the bag and a quarter drops into the box. And that, much of America thinks, is how UNICEF raises money to help feed, heal and educate needy children around the world.

|

But while the Trick-or-Treat campaign is the public face of UNICEF in the United States, its share of the organization’s fundraising has been steadily shrinking – so much so that last year, Trick-or-Treat accounted for about 1 percent of the $374 million in revenue to the U.S. Fund for UNICEF. In fact, raising money might not even be the biggest benefit of the campaign.

“I am not so concerned about raising millions and millions of dollars through this program,” says Kim Pucci, marketing director for the U.S. Fund for UNICEF.

That’s because the famous campaign has been eclipsed by an income diversification plan that has helped boost the U.S. Fund’s revenue by 500 percent over the past decade.

And the Halloween campaign – one of most successful uses ever of youth as fundraisers – has changed markedly over its 57 years. It has used manpower reductions, technology, targeted marketing and even service-learning to become far more efficient. The single day, door-to-door routine continues to fade.

|

Today, the campaign is not so much about raising money for the moment as it about marketing for the future. The U.S. Fund believes that exposing the UNICEF brand to the public, and getting youths and adults into the practice of contributing to UNICEF, eases the way when it comes calling for donations years later. Last year, the fund says, 5 million youths were involved in the campaign.

“The underlying value of Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF is that you are giving [adults] the opportunity to introduce to children at the earliest possible stage … to the idea of philanthropy,” says Chip Lyons, former president of the U.S. Fund.

“We want to have a lifelong relationship with our donors,” Pucci says. “If we are seeding a donor of the future, if we are creating caring and empathetic kids, then we are succeeding.”

An Idea Takes Off

|

|

Faces of charity: A common site when people open their doors on Halloween. Photo: Photo courtesy of U.S. Fund for UNICEF |

According to UNICEF, the Halloween fundraiser started in 1950, when a Presbyterian minister in Philadelphia, Clyde Allison, and his family collected $17 in coins on Halloween night, donating the money to UNICEF.

UNICEF (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund) was created in 1946 by the U.N. General Assembly to help children in Europe and Asia after World War II. It is funded entirely by contributions, and the U.S. Fund is a nonprofit fundraising arm of the U.N. agency.

So when Allison sent in his Trick-or-Treat proceeds to the U.S. Fund, it became a logical addition to the group’s initial fundraising tool: the sale of UNICEF greeting cards created by children.

Trick-or-Treat has raised $137 million to date, UNICEF says. The campaign’s revenue collection peaked in 1971, when it brought in $3.4 million, accounting for more than half of the U.S. Fund’s revenues and contributions.

But it was a labor-intensive effort. At one time, hundreds of volunteers and staff were spread across the country to manage the campaign through schools, religious organizations and a limited number of youth clubs; they distributed coin boxes, provided education materials and handled the donated money, which was delivered to regional collection centers.

“Up until 10 years ago, we literally had people in back rooms rolling coins” in wrappers, says Christine Squires, the fund’s vice president of direct and interactive marketing.

For all of that work, “a box of Trick-or-Treat coins might collect $5 or $10,” notes Lyons, now director of special initiatives in global development at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. “Even if we get hundreds of thousands or millions of these transactions,” it wouldn’t match what could be raised through other means.

Indeed, after its peak in 1971, Trick-or-Treat accounted for a shrinking share of the U.S. Fund’s total revenue. In 1997, the campaign raised $3 million – about 5 percent of the fund’s $60 million in income that year. Other revenue streams, such as support from corporate partnerships and donations from direct marketing, were growing.

A decade ago, the fund set out to restructure how it raised and handled money through Trick-or-Treat, and to significantly boost funding through other strategies.

Making Change

|

|

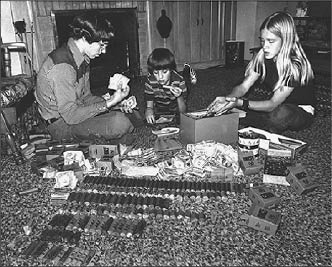

Rolling along: UNICEF fundraisers count coins, 1972. Photo: Photo courtesy of U.S. Fund for UNICEF |

Even with Trick-or-Treat contributing a dwindling share to of the fund’s income, its value grew as an icon. In this way it is much like the Salvation Army’s Red Kettle Christmas campaign. The army reports that the campaign netted $117 million last December, or 7 percent of its reported $1.64 billion in public support.

“Keeping a signature event is vital for name recognition and public reputation,” says Kirsten Gronbjerg, who holds the Efroymson Chair in Philanthropy at Indiana University. “You can later advertise to prospective donors” who were involved in the past.

Pucci notes that UNICEF’s 2006 Trick-or-Treat tracking study found nearly half of all parents surveyed said they had Trick-or-Treated for UNICEF when they were kids.

The fund instituted several strategies to make the campaign more cost-effective:

• Technology: Trick-or-Treat fundraisers are now guided to some 12,000 Coinstar machines in supermarkets nationwide. They drop in their coins, the machine tallies the cash value, and Coinstar sends that much money to the fund. Approximately one-fifth of Trick-or-Treat donations come through Coinstar machines, the fund says.

Coinstar offers a fee of 7.5 percent to nonprofits, compared with a standard fee of 8.5 percent, which Squires says “is less expensive than if the coins were processed in-house.”

While the majority of revenue comes through coin and cash donations, the fund started an online fundraising program called Friends asking Friends. Each campaigner can customize the fundraising program, and donors can use credit cards online.

Individuals, who raise about 15 percent of the money each Halloween, can order coin boxes online or pick them up at Pier 1 or Hallmark Gold Crown stores.

• Efficient Marketing: More and more, the campaign has focused on schools as the most efficient way to reach and organize its legions of youth volunteers. School-sponsored bake sales, costume parties, car washes and other special events bring in most Trick-or-Treat contributions.

Each September, about 4,600 schools receive Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF kits, which include fundraising materials, 10 coin collection boxes, and such resources as posters, recipes, bake sale ideas and a DVD about UNICEF’s global work.

The direct mail effort has “reduced costs and increased the number of donors,” Squires says. Such marketing efficiency is the main reason that youth-serving organizations have not been involved much in the campaign. The fund believes it reaches the same youth at their schools.

• Staffing: Historically, staff distributed boxes and collected coins after Halloween. Thanks to the changes above, the U.S. Fund has gone from a dozen or so staffers working on Trick-or-Treat in the field in 1997 to none today. The fund manages the program from headquarters in New York.

• Service-Learning: Trick-or-Treat has also reached into high schools by tapping into the service-learning movement. Now, significant donations come from high schoolers who participate in Key Club International, the service leadership program of Kiwanis International. Teens involved with Key Club International receive service-learning credit at their schools when they Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF.

More changes are in the works. The fund will unveil a new Halloween-related retail item this year, Squires says, and plans to leverage the Trick-or-Treat brand through licensing, costumes and safety items by 2008. The website now includes fundraising tips for kids and interactive games, such as Halloween Coin Toss (www.unicefgames.com).

“We use our online presence to engage youth in what UNICEF does,” Squires says.

Contact: U.S. Fund for UNICEF (800) 486-4233, http://www.unicefusa.org.

Diversifying Revenue

While making changes to Trick-or-Treat over the past decade, the U.S. Fund for UNICEF also diversified into other funding avenues.

“We had to … run the organization as a business,” Lyons says. “We had to understand and learn about return on investment. If we invested more in direct mail or internet giving, what was going to be the return to the organization for the investment?”

Among the strategies that the fund has employed or boosted:

• Direct marketing: It includes an e-mail newsletter to more than 600,000 people each month. Individuals comprised 26 percent of total support and revenue last year. Major gifts totaled $27 million, up 35 percent from the prior year.

• Corporate partnerships and alliances: More than 66 percent of contributions came from corporations last year. Pier 1 Imports has long been a campaign supporter, donating $26 million to date and distributing free Trick-or-Treat coin boxes each October. Among the newer partners are Cartoon Network and Procter & Gamble.

For the second year, Hallmark Gold Crown stores will distribute coin boxes and sell Halloween greeting cards for UNICEF. “A nonprofit organization can only take a greeting card so far,” Lyons says. “When you consider the market penetration of Hallmark, they have the resources to invest, the placement, the creative direction that we were never able on our own to generate.”

Other corporate partners include Microsoft, American Express and Gucci.

• Donor retention: When the South Asian Tsunami hit in 2004, UNICEF donors ponied-up a record-breaking $5 million a day in the first few days of the disaster. The fund used thank you notes and other strategies to help retain the 260,000 new donors.

• Donations of medicine and medical supplies: Of the fund’s $373 million in reported revenue last year, $227 million was in donated products and services, mostly medicine and medical supplies.

But exploring new funding sources requires more investment in administrative costs. In 2005, the American Institute for Philanthropy gave the U.S. Fund a C- rating, citing higher than necessary fundraising costs and a lower percentage of cash expenses going to programs that year.

“The dilemma that most nonprofits face is that each funding source requires fairly extensive management efforts,” says Gronjberg at Indiana University.

The fund has worked to tighten costs. Towers says that fundraising today accounts for 6 percent of overall expenses, compared with just over 9 percent last year. For the past three years, the fund has received a top efficiency rating from Charity Navigator, an independent agency that rates nonprofit entities. The American Institute for Philanthropy now gives the fund an A.