Like a lot of community-based organizations aimed at troubled youth, the Oasis Center in Nashville began by trying to do a lot for the kids when it opened 38 years ago. Gradually, however, the staff realized that kids responded best when they were learning to help themselves and their communities. So today, the center focuses largely on guiding the youth in community service and civic engagement, through such activities as teaching financial literacy to adults and fellow students and lobbying to improve city schools.

“Civic action has proven a successful strategy for reaching older youth,” says Oasis Center President Hal Cato. “It provides a forum for them to reflect on the challenges their families and communities are facing.”

More and more agencies have been discovering the same thing in recent years, as community service and civic engagement continue to grow. While that growth will be celebrated with special events around the country in April – National Youth Service Month – it’s worth noting how some agencies have made youth service not so much a special event as a standard strategy of youth development.

A recent study conducted by the Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development and sponsored by the Ford Foundation tracked the effects of civic action by 12 community organizations around the country. The study, “Youth Development and Leadership Initiative” (YDLI), found that community service reached youths who seemed “unreachable” in more traditional youth development programs. By focusing less on their personal issues and more on larger societal problems, youths addressed social and economic barriers facing not just themselves, but their families and communities.

The YDLI study showed that 69 percent of young people in programs focused on community service reported high-quality relationships with adults and other young people in the organization, as opposed to the 35 percent to 40 percent reported by traditional youth programs. Forty-two percent of youth in organizations that encouraged youth participation had access to leadership roles, compared with 8 percent in adult-led youth development programs.

|

|

TRAIL-BLAZING WORK: Youths from the Coconino Rural Environment Corps construct a trail in Arizona.

Photo: CREC |

“Many young people are ready and willing to work hard on social issues,” says Innovation Center President Wendy Wheeler. “Often, the roadblocks are placed by adults who lack skills and training in youth-adult partnerships.”

More organizations are trying to eliminate those roadblocks.

“Weaving community transformation in with personal transformation is really powerful,” says Patricia Bravo of the Latin American Youth Work Center, in Washington. She helps run the YouthBuild Public Charter School, where students help build low-income housing to learn not only construction skills, but life skills that will help them succeed in various careers and as self-reliant adults.

For instance, Bravo says one of the school’s construction trainers recently found a student crying in the hallway because her boyfriend had put his fist through the wall in her apartment. Her landlord told her it was her responsibility to fix it, but she didn’t have the money. Bravo says the trainer handed her a bucket of joint compound and drywall tools and said, “You know how to do this.” She fixed the wall.

Such stories don’t surprise Wheeler, who believes youth handle their lives better when they feel empowered to change not just their own destinies, but the destinies of their communities.

“Kids want to make their hometowns a better place,” Wheeler says. “They see the impact of injustice on their families.” She says civic action often gets kids asking questions like, “What are my responsibilities to my community?” or “What does it mean to be American?”

The concept of getting young people involved in the community isn’t new. But many youth programs are stepping beyond having kids pick up trash or paint houses in a rundown neighborhood – not that there’s anything wrong with that. It’s just that many agencies find the most powerful and consistent form of service to be civic engagement.

“You can paint somebody’s house, but you have to ask why that person doesn’t have affordable housing,” says Alexie Torres-Flemming, founder of Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice, in the South Bronx. She believes true civic engagement for young people doesn’t involve just working in a soup kitchen, but figuring out why a community needs a soup kitchen.

Such activism, however, brings a risk. While civic engagement programs have little trouble recruiting youths, they often have trouble raising funds.

Torres-Flemming says that when a program verges on activism, it’s hard to get funding support from government entities, which fear funding projects that someone might object to for political reasons. That leaves the agencies to rely more on the private sector, or to raise funds through the very services that youths provide, as the Coconino Rural Environment Corps does in Arizona.

That’s one twist about youth service: It’s not always free. In YouthBuild programs, for instance, youths get paid hourly wages to fix homes for poor people.

Following are four youth organizations that take different approaches to youth service.

Deborah Huso can be reached at dhuso@youthtoday.org.

Faith-Based

Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice

Bronx, N.Y.

(718) 328-5622

http://www.ympj.org

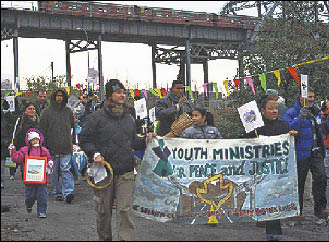

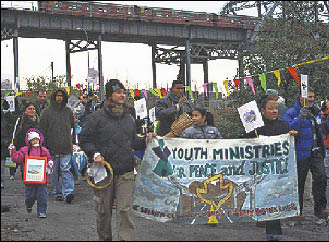

The Approach: Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice (YMPJ) is an urban ministry program based on the idea that community organizing and activism promotes youth development. The organization runs after-school programs that encourage kids to help solve the problems plaguing the South Bronx.

When young people enter the program, they receive training in community action – first learning how to be youth organizers, then designing community improvement projects with their peers. A key component of YMPJ is using arts for activism. The idea is to get kids who might be interested in the arts as entertainment to see art as a way to communicate injustice and promote community activism.

Each semester, three teams of youth each come up with three main projects, with those designing the top projects winning $500 college scholarships, says Executive Director Alexie Torres-Flemming. YMPJ facilitators help kids develop budgets and strategies for community projects.

Recent projects include an “Asthma: Breathe or Die” campaign, in which kids addressed the problem of pollution from local highways and a concrete plant.

Other campaigns have focused on awareness of pollution in the Bronx River and efforts to make it swimable and fishable. The youths caught fish in the river and had them tested for contaminants. Then they created a campaign to educate local residents who fish in the river about which types of fish were safe to eat and which were not, and how often they could safely eat the fish.

Those who want to engage in long-term work on a project can apply for one of YMPJ’s 25 part-time positions, which pay $8 an hour. One such project involves working with several local organizations on a Bronx River Greenway to improve public access to the river and turn an abandoned concrete plant along the river into a city park.

History and Organization: Torres-Flemming founded YMPJ in 1994, when she moved back to the South Bronx, where she was born and raised, after leaving a job in Manhattan at the Association of Puerto Rican Executive Directors. “Kids like myself were taught to get up and out of the neighborhood,” Torres-Flemming says. But she realized that the South Bronx, which is one of the poorest congressional districts in the United States, was not getting any better by encouraging its best and brightest to leave.

|

|

GOING PUBLIC about community issues and the work of Youth Ministries is a regular practice.

Photo: YMPJ |

To make ends meet while setting up YMPJ, Torres-Flemming relied on unemployment checks, her savings and her family. She built the agency on the belief that in order for a youth organization to make an impact in such a poor neighborhood, its activities could not be separated from the community as a whole. “We frame our work as youth and community organizing,” she says. “Sometimes community service is a band-aid that doesn’t get to root causes.”

Youth Served: About 150 a year, ages 13 to 20. Torres-Flemming says all the youths live below the federal poverty level, and the vast majority are African-American or Latino.

She says recruiting young people isn’t hard. “We’re the only game in town,” she explains. “Recruitment is mostly by word of mouth. This is a place to come after school, and it’s a loving, nurturing environment.”

Staff: Twenty employees, plus up to 25 kids working part-time. Other youths serve as interns.

Funding: YMPJ began with a $35,000 grant from the New York Foundation and with donated space at a local church. Today it runs on an annual budget of $1.5 million, with most of the funding coming from the private sector. Funders include the Funders Collaborative on Youth Organizing and the Surdna, Levitt and Merck Family foundations. Last year YMPJ got a $150,000 earmark from the U.S. Department of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, but Congress eliminated all of those earmarks this year.

Torres-Flemming says funding can be a challenge, because YMPJ’s youth work is not traditional. “There is an idea in the funding community that these programs are too activist in nature,” she says. That’s one reason that private funding sources have become so essential.

Indicators of Success: “The group’s first campaigns helped close an illegal social club, keep an elementary school open over the summer for youth programs, and save public funding for 700 summer youth jobs,” according to a 2004 study (“Youth Organizing”) by Philliber Research Associates.

Torres-Flemming says YMPJ measures its impact in several ways, including participant surveys, focus group discussions, school test scores and report cards. “We find our young people fare better in terms of finishing school” than do youths in the public school system in general, she says. She said YMPJ kids’ on-time graduation rate is 88 percent, well above the city rate as a whole.

Community activism has inspired some youths to say they want to stay in the South Bronx rather than find the quickest way out. “Feeling they can make a difference to the world,” Torres-Fleming says, “makes a difference to them and changes their goals about the future.”

GOING OUTDOORS

Coconino Rural Environment Corps

Flagstaff, Ariz.

(928) 522-7986

http://www.crecweb.org

The Approach: The Coconino Rural Environment Corps (CREC) is a county program that engages high school and college students in environmental conservation in Arizona’s state parks, national parks and other government-owned land. Participants spend anywhere from three months to a year on trail maintenance and construction, invasive species control, habitat and watershed restoration, and forest fuel reduction. Participants often camp on site for up to eight days at a time.

|

|

CHAIN REACTION: A CREC member works on a project to reduce forest fire fuels (like dead trees).

Photo: CREC |

Dustin Woodman, CREC’s interim program manager, says recruiting kids for conservation work isn’t difficult. “There’s a great tendency for young people these days to want to serve their communities,” he says. “Young people are attracted to the outdoors and want to get involved in environmental issues.”

Woodman says students not only learn important skills in land management, but also get leadership opportunities. The supervisors of CREC’s eight-member crews are usually former CREC participants, while the assistant supervisors are selected from the youth crew members. “The root of the program is the idea that through service to the community, students will gain a stewardship ethic,” Woodman says.

Woodman says he cannot overemphasize the positive effect of environmental programs on getting young people outdoors and promoting conservation of the natural world. “One of the benefits of a program like ours is its hands-on nature,” he says. “When you’ve thinned 100 acres of a community at risk for wildfire, that kind of accomplishment is very powerful and concrete.”

History and Organization: CREC is modeled on the Civilian Conservation Corps of the 1930s and ’40s, employing young people in environmental and conservation work designed to enhance public lands and protect private property from natural hazards.

CREC began in 1997 as a partnership between the U.S. Forest Service and Coconino County to promote conservation work by young people on public lands in the Flagstaff region. The project was initially funded by AmeriCorps, which still provides some of the funding. In 1999, the Forest Service transferred the program to Coconino County, which now manages CREC on its own.

Youth Served: About 120 to 140 young people participate each year in two programs, Woodman says. The Youth Conservation Corps is open to 15- to 18-year-olds, mostly from the Flagstaff area, who do conservation work during the summer. The Young Adult Conservation Corps, for ages 18 to 25, takes people from all over the country for three, six or 10 months.

CREC recruits participants through advertisements in local newspapers, high schools and colleges. Nationally, it recruits through the AmeriCorps website.

Participants receive a stipend equal to about $580 every two weeks and are eligible for AmericCorps education awards for continuing education.

Staff: Ten permanent staff members, and three to 10 “temporary” staffers, most of whom supervise work crews.

Funding: The annual budget is $1.6 million. Woodman says CREC is largely self-sustaining, bringing in 85 percent of its funding from service fees charged to organizations for its conservation work. The rest comes from an AmeriCorps grant through the Arizona State Commission.

Indicators of Success: Woodman says CREC has a variety of performance measures, the most basic of which measure accomplishments on the ground, such as how many trail miles a crew constructed or how many acres of land were cleared of wildfire fuel.

Each program participant completes entry and exit surveys, which gauge how the program affects a youth’s career aspirations, connections to the community or self-perceptions. According to CREC, 83 percent of program graduates report “an increased sense of civic engagement and responsibility,” while 47 percent say they intend to pursue volunteer activities after graduation.

CREC is one of 22 sites participating in a National Youth Corps Study that will better quantify and qualify the impacts of youth service programs on young people.

Some indicators of success are anecdotal. “Some kids really find their place in the community as a result of participating in CREC,” Woodman says. “Some kids will say it was the best year of their life.”

Construction

Latin American Youth Center / YouthBuild Public Charter School

Washington, D.C.

(202) 319-2236

http://www.layc-dc.org/charterschools/youthbuildpcs/index.html

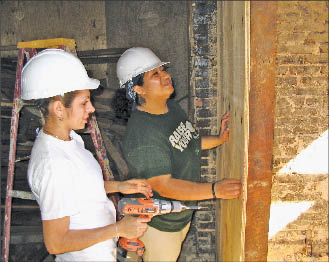

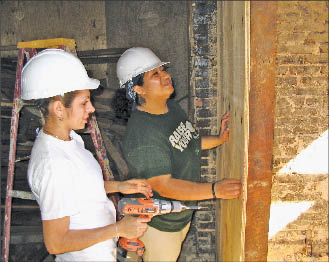

The Approach: The Latin American Youth Center’s (LAYC) charter school model follows that of YouthBuild programs around the country. The youths build housing for low-income or homeless families under the supervision of a construction manager. Youths are paid $7 an hour for their work, and $10 for each day of classroom instruction.

“A lot of the kids feel this is a way to give back to a community they’ve taken from in the past,” says the school’s executive director, Patricia Bravo. One recent student, for example, had served time for drug dealing, while another had been involved in gang violence.

During the one-year program, the students typically alternate between the classroom and the construction site, spending two weeks on the job and two weeks in class. The classroom work focuses on GED training, life-skills and computer training, job readiness and financial management.

|

|

BUILDING FUTURES at a construction site.

Photo: LAYC |

“When they’re on the job site, they go directly there, not to the school, so it creates a very job-like environment,” Bravo says. “They have to get there themselves, and they have to punch in to receive their stipend.”

The program works in partnership with a low-income housing developer. The students receive directions and assistance from a construction manager and two construction trainers employed by the charter school.

History and Organization: LAYC began its YouthBuild program 12 years ago to address the problem of older youth who had dropped out of school and were hanging out at the center with nothing to do. LAYC applied for a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development grant to start the program and modeled it on one it had observed in Harlem.

Two years ago, in an effort to create additional funding streams, LAYC started the YouthBuild Public Charter School, which combines on-the-job training in construction trade, community service and classroom instruction for passing the GED test. “Establishing the charter school allowed us to serve more youth, provide more services and get more funding,” Bravo explains.

Youth Served: Last year the charter school served 65 students, ages 16 to 24. Most participants are high school dropouts or have been expelled from school. Sixty-five percent are African-American and 34 percent are Latino. More than half of the latter have limited or no English skills. Students are divided pretty evenly between male and female.

Most enter the school reading at or below the sixth-grade level. “Some of these kids have been out of school five or six years,” Bravo notes.

LAYC’s recruitment includes hiring about four alumni each year to hand out flyers in malls, clubs and other places where kids congregate.

Staff: The school has 14 employees, six of whom are teachers. “It’s hard to recruit staff,” Bravo says. “It’s hard to find people for the construction training. They have to want to do this kind of work and be able to work with young people.” Bravo says two of the school’s construction trainers are alumni.

Funding: The annual budget is $1.5 million. The vast majority of funding comes from the city’s public school system, which provides $9,000 per pupil each year for kids 18 and under, and $6,000 per pupil for those over 18.

Funding was a primary reason LAYC turned its YouthBuild program into a charter school. Bravo notes that “with more than 200 YouthBuild programs in the country, there was lots of competition” for the federal funding. (YouthBuild’s federal funding has been flat in recent years, at $50 million annually, which is $15 million below its 2004 funding.)

“Now that we’re a school, we get more money, and we have special education services,” Bravo says. “It’s helped us gain financial stability.”

Indicators of Success: Bravo says the school tracks improvements in math and reading, how many students pass the GED test, and how many go on to college or to get a job. “About 80 to 90 percent of graduates go on to get jobs or to pursue post-secondary education,” she says. She notes that only about 10 percent of graduates pursue careers in construction.

The center reports that among last year’s 33 graduates, 23 increased their reading proficiency by two or more grade levels, and 26 increased their math proficiency by two or more grade levels. Only one-third of those graduates received their GEDs. Bravo says it is not uncommon for students to come back for a second year of instruction, then pass the GED test.

Youth in Charge

Oasis Center

Nashville, Tenn.

(615) 327-4455

http://www.oasiscenter.org

The Approach: The Oasis Center’s youth-led civic action tends to focus on problems in Nashville’s schools and in the foster care system, says President Hal Cato.

The center’s Youth Innovation Board (YIB), which is composed of 22 youths from schools all over the city, is working on a two-year program to improve the learning climate in Nashville schools. The youths created a student survey to find “silent risk factors” for dropping out of school. It was completed by 41 percent of the students in Nashville’s 15 city high schools, Cato said.

The survey found that youths in the city’s standard (“comprehensive”) schools are much less likely to graduate and less likely to demonstrate high academic performance than are those in magnet schools. Cato says YIB will use the results to create an action plan to present to city and school system leaders. Among the recommendations: a student bill of rights to make sure all students have access to college counseling and resources, and changing the rules for student suspensions, which can put at-risk kids even more behind in school.

|

|

YOUTH LEARNING teamwork skills during an Oasis Center retreat.

Photo: Oasis Center |

Through the center’s Oasis Community Impact program, youth work as part-time employees to staff an office at Stratford High School year-round. They provide financial literacy counseling and help students get access to post-secondary education information. Cato says 80 percent of Stratford students would be first-generation college students if they pursued post-secondary education.

Community Impact is also working with the local Junior Achievement to create a financial literacy program for poor youth. “Most of these families make less than $9,000 a year,” Cato says, so traditional financial counseling doesn’t make sense for them.

History and Organization: The Oasis Center began in 1969 as a grass-roots citizen group that provided a drop-in center for young people in crisis. About a decade ago, the center began shifting its mission from just helping at-risk kids to teaching them to help themselves and their communities. “We’re moving young people from the role of passive client to the role of engaged citizen,” Cato says.

Today, the center has 17 youth programs, many of them focused on teaching kids to help themselves. Youth serve as both employees and board members, and help to run many of the center’s community action programs.

Youth Served: Cato says about 1,400 young people, ages 12 to 22, participate in center activities throughout the year. About 76 percent are considered low-income.

“They represent Nashville’s diversity,” Cato says. “We have African-Americans, whites, immigrant and refugee populations. We also have the largest Kurdish community in the U.S.” The 2000 U.S. Census tallies the city’s Kurdish community at 5,000 people, larger than the number in any other community.

Social workers and guidance counselors refer kids to Oasis Center. Other youths hear about it through word-of-mouth.

Staff: The center has 63 employees, nine of whom are students. Students serve on the board of directors and hiring committees and have run the center’s annual giving campaign.

Funding: The center’s budget is just over $3 million a year. Cato says one-third of its funding comes from grants from local companies and foundations. Major funders include the United Way of Metropolitan Nashville, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the U.S. Family and Youth Services Bureau, and some state agencies.

Indicators of Success: Cato says the Oasis Center’s own impact surveys have shown that getting kids involved in their communities can improve their development. “On a very basic level, we measure success as a young person being able to stay in school or go home to a safe environment,” he says.

The center reports that 82 percent of the fiscal 2006 participants in its Community Impact program reported that the program had increased their sense of belonging in the community. Ninety-one percent said the program had given them a better sense of self-efficacy.

The Oasis Community Impact program was one of 10 finalists last year for the Peter F. Drucker Award, granted by California’s Peter F. Drucker and Masatoshi Ito Graduate School of Management at Claremont Graduate University to honor programs that make a difference in the lives of others. One of the Community Impact program’s “youth mobilizers,” Star Martin, was honored last year by the Hitachi Foundation as one of nine outstanding “change agents” around the country, for her work in educating her community about predatory lending.