After living in 14 different foster-home placements, 14-year-old Alex (name changed) said she felt depressed and isolated. Like the estimated 400,000-plus other children currently living without a permanent family in the foster care system, Alex has experienced childhood trauma and moved from home to home.

She had threatened suicide, which led to her being hospitalized. She said she did not feel able to communicate her feelings to her caregivers.

Many foster youth like Alex struggle to stay within a home or a community for the long term. On average, young people in foster care go through more than three placement changes, and 65 percent experience seven or more school changes.

Alex’s foster family wanted to give her a more stable home and lifestyle. The Alameda County child welfare system referred them to the nonprofit Lincoln Child Center’s Project Permanence.

Project Permanence is a wraparound program for youth as young as 2 years old and as old as 20, designed to support “permanently placed foster youth in their transition out of a group home or other temporary placements into stable family homes with caregivers committed to a life-long permanent relationship,” according to the agency website.

The program, funded by the Department of Children and Family Services, also “supports foster youth who are at-risk of losing their permanent placement.”

The term “wraparound,” coined in the 1980s, refers to helping people who have complex needs via a structured, creative and individualized team planning process. The California Department of Social Services defines wraparound as a planning process that engages a child and his or her family via therapeutic, individualized services to improve their well-being and ensure a safe, stable and permanent family environment.

The National Wraparound Initiative has worked to support these services across the nation for the past 10 years, conducting research on the success of these models and training professionals.

“The whole team works with the family to wrap around the family, wrap around the child and wrap around the community to create the shifts they need to support them,” said Project Permanence Program Director Kim Catanzano.

All the young people who come through Project Permanence suffer from a mental health issue. According to the Child Welfare League of America, anywhere from 40 to 85 percent of kids in foster care have mental health disorders, depending on which report you read.

Sarah Zahedi

CEO Christine Stoner at Lincoln Child Center.

The wraparound model is far more accommodating to foster youth dealing with trauma and mental health issues than the traditional model of putting youth struggling with permanence into a group home, said Lincoln Child Center CEO Christine Stoner-Mertz.

“These kids have dealt with poverty, community violence, domestic abuse, substance abuse, mental health issues — you name it. The whole idea behind wrap is it’s got to meet that family’s needs, their culture, their religious traditions,” Stoner-Mertz said. “It’s really about what that particular family needs, even though there are similar themes across families.”

In Alex’s case, Project Permanence helped her stay within her foster family. Through the program, she worked with three different Lincoln Child Center staff members, including: a family partner, someone who lived the experience of having a child go through the foster care system; a community liaison, who worked to engage her with her community; and a clinician who helped work through her mental health issues.

Over a year, they met with Alex’s family weekly, working with Alex to help her express herself through therapy and various writing exercises. The team worked to educate Alex’s foster parents on the importance of compromise, which helped the family better understand each other.

[Read: Youth Today’s full foster care coverage]

Alex said she was eventually able to become comfortable with her parents, expressing her understanding of their concerns and being able to talk about her own successes and efforts.

Catanzano said having three different people supporting families is helpful for young people like Alex to build lasting adult relationships and connect with their families.

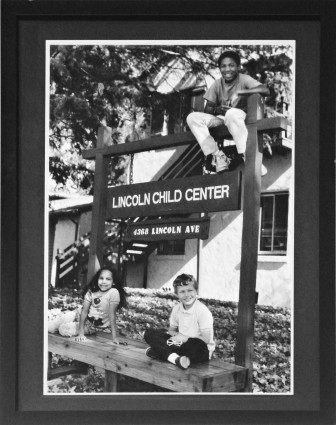

Sarah Zahedi

Historical shot from the offices of the Lincoln Child Center.

“There can be a lot of uncertainty on the part of both the parent and the child initially,” Catanzano said. “So, that’s the nice thing about having a whole team, because the kids can choose who they are comfortable with and open up to them. It’s more hands to support the child.”

During the program, families also hold monthly meetings with the Project Permanence team as well as anyone else from the child’s life they would like to invite, like a therapist or a next-door neighbor. Through the meetings, Catanzano said, the family begins to gain independence.

“The meeting drives what the next month will look like, and how you get there is up to the family and their supports,” Catanzano said. “There is some handholding in the beginning and then stepping away or bringing someone else in so that the family moves forward on their own and starts calling their own team meetings.”

Six months after the Project Permanence team stopped working with Alex’s family, she is still living with the same foster family, who, through hard work and hopefulness, were able to develop a stronger and healthier connection with her.

Approximately 80 to 90 percent of the families who have gone through the Project Permanence program since 2007 remain together at least six months after the program in stable placement, Stoner-Mertz said.

The program lasts six months to a year in an effort to have these families learn to implement Project Permanence’s unique strategies with each young person on their own. However, in some cases, Stoner-Mertz noted that families might need a little bit more time, which the center works to accommodate.

“The idea is not that we are there forever,” Stoner-Mertz said. “The idea is that you’re helping the families to gain the knowledge and tools they need so that when they need something and we’re gone, they know how to get that resource. You don’t want them to be depending on the nonprofit system in the long run.”

“Sometimes when we start, there’s the hope of, ‘Can you take my child, bring them out of the home, and fix them and come back,’” Catanzano said. “We are not about that, we are about some of that — taking the youth out to bring them on outings and supporting the youth individually — but also we have to have the family and other providers participate so everyone is on board with the wraparound process.”

For young people who don’t receive wraparound services and are at risk of entering an impermanent foster care placement, Stoner-Mertz said a majority end up in a group home setting, continuing to face unstable living situations.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 101,666 foster children are eligible for adoption, but nearly 32 percent of them will wait more than three years in foster care before being adopted. Many do not get adopted at all, with only 49,866 of about 400,000 foster youth being adopted in 2011.

Stoner-Mertz said the lack of available permanent foster homes for youth is part of the reason wraparound services are so important.

“The government is not in the business of housing children and trying to educate them there, when what you really want them to be in their local schools and getting those supports there,” Stoner-Mertz said. “Our goal is that we can continue to focus our services on more prevention and early intervention and provide them in the youth’s communities and schools so that the more intensive services like group home placement aren’t even required anymore.”

“If a child has had significant trauma, being removed from the family of origin and living in many places, they might just have behaviors where they are just acting out and it makes it hard for them to stay in a family setting,” Catanzano said. “We come in to support the family and child and the foster care system so the parents and child have what they need to be successful versus just sending the child to therapy. It’s a family approach.”

More related stories:

Finding a New Life through Quality Residential Care

Senators Push to Keep Kids Out of Foster Care

Making Health Care Access Easier for Young People Leaving Foster Care

Legislation Would Keep Foster Kids From Having to Change Schools